Several members of the old ER gang — showrunner John Wells, executive producer R. Scott Gemmill and star Noah Wyle — have reconvened for the new Max series The Pitt. It's set in familiar territory but requires a whole new map.

The Pitt, which was recently renewed for a second season, takes place in a Pittsburgh emergency department. This season follows a single 15-hour shift, with each episode covering one hour. Wyle (The Librarians, Falling Skies), who also writes on the series, plays Dr. Michael "Robby" Robinavitch, the deeply conflicted head of the emergency department. Gemmill (NCIS: Los Angeles, The Unit) is the creator and showrunner, and Wells (Shameless, Rescue: HI-Surf) directed the first episode; all three serve as executive producers. During a break from shooting episode 13, the trio gathered to discuss their working reunion and crafting a new format to suit a contemporary medical drama.

Okay, who started this?

Noah Wyle: I think we came to the same idea almost at the same time. During peak Covid, I was home, as we all were, not working, feeling pretty useless, and I was getting a lot of mail from first responders. They were saying thank you for having inspired them to go into a career in emergency medicine — or keeping them inspired while they were going to work in what was amounting to a nightmare. I was overwhelmed by those letters, and I didn't really know what to do with them, so I sent them to John and said, "Hey, John, outside the birth of my kids, that show may be the best thing I ever did with my life, because we may be indirectly responsible for saving lives right now. I know you don't want to do the show again, and I don't really either, but if you ever want to talk about what's happening right now and need someone to scream from a mountaintop, I volunteer." That's where it was born, out of this need to shine a light back on this community that needed a morale boost, that was being asked to do the impossible without a break.

R. Scott Gemmill: For me, it came out of a conversation with another writer about why I would never do a medical show again, because we had done it so well. Anything we approached would be compared to that — unless there was a way to do it new and fresh that made it feel like it was worthy. I reached out to Noah to see if he was interested, and he had already been in the process, and then I went to John.

Things have gotten better in some ways with emergency medicine, with the technology, but a lot of things haven't. It's still the safety net for most of the country. Many of society's ills first show up in the emergency room, whether it's Covid or the fentanyl epidemic or the amount of unhoused people. It's sort of the canary in the coal mine for what's happening.

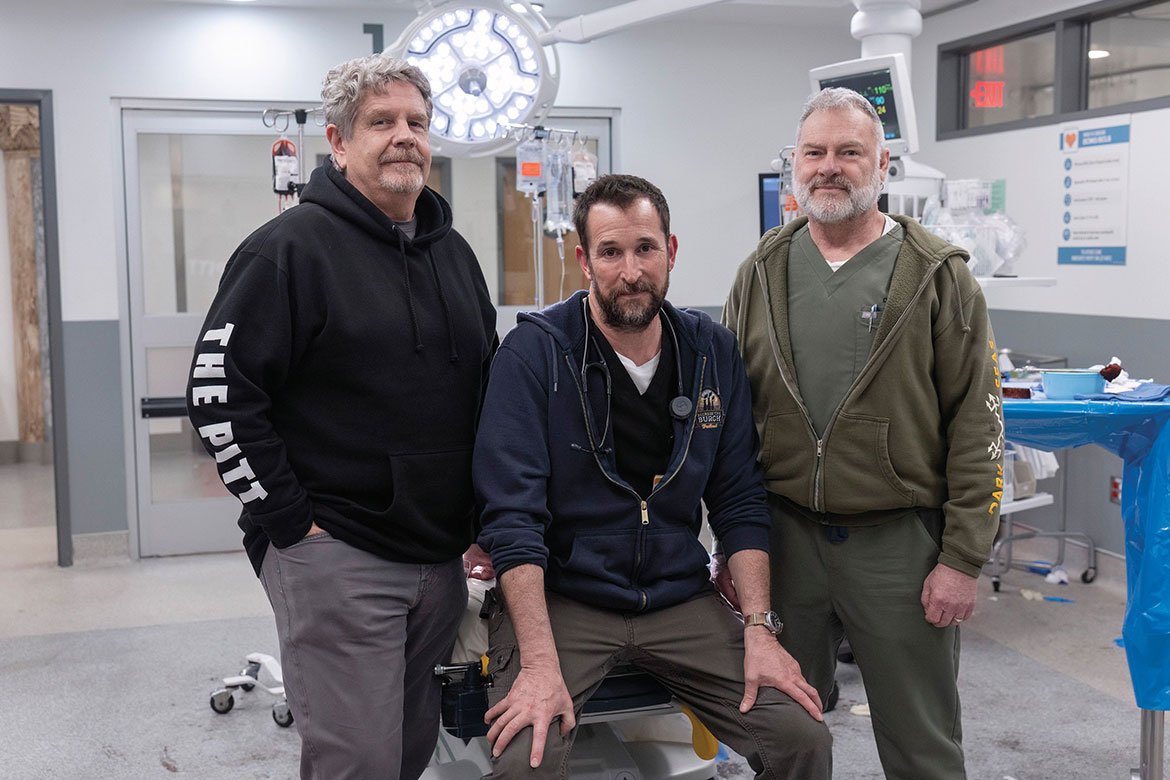

John Wells, Noah Wyle and R. Scott Gemmill on the set of The Pitt. Photo Courtesy: Warrick Page/Max

John Wells, Noah Wyle and R. Scott Gemmill on the set of The Pitt. Photo Courtesy: Warrick Page/Max

John Wells: There are significant new problems within the healthcare system, particularly within urban medicine, that have reared their heads. A number of physicians we worked with before, who are still practicing medicine, started to tell us these stories, and it was like, well, I guess there is a reason to go back and to think about these issues in the healthcare world, particularly in emergency medicine and urban medicine. Dr. Joe Sachs, one of the great ER writers, and a coexecutive producer, has been in contact with everyone, so we were hearing a lot about it as it went on.

Who came up with the idea of a season following one shift?

JW: I think it was this lunatic, Scott, who is still questioning whether or not it was a good idea.

RSG: That came out of what could make it different. The thing that makes the emergency department somewhat unique to all forms of medicine is the time. Trauma victims come there with moments to live. The emergency department has such a frantic pace, and the doctors are being pulled away every couple minutes, and the only way to really capture that is to get in it and stay in it for the whole shift. If you come back and it's a day later, there's a lackadaisical quality to it, but that's not real. It was really challenging, and we didn't know if it was going to work, but I think we've proven it does.

Did you have to storyboard all 15 episodes together?

RSG: Yes.

That sounds insanely hard.

[They laugh.]

NW: I'll speak to the degree of complexity, because Scott's probably too humble to do it. You have to track the patient journey for every single patient who's been admitted, knowing that every doctor is going to see four patients an hour, and we are committed to 15 hours. In addition to that, the background performer that you see is on their own individual patient journey, and at a certain point they're going to get fed, and they're going to get taken to the bathroom, and they're going to get their bed changed. We have an entire second unit operating within our main unit that just does that — that just moves the administration, hospital and environment services through the background in real time, in concert with our foreground action and storytelling.

RSG: I have giant maps of our set, and for our writing staff, it's like a game of Risk. We have little pieces for all the doctors, and we go through and track them. We shoot every episode in continuity, because there are so many chess pieces that there's no way to shoot an actor in this and know what's going on in the background of the set, which is completely open. You can see in every single direction, so there are three or four levels of action that are happening in every shot. [Production designer] Nina Ruscio designed it before we started writing, so that the series could be written to the set.

NW: There's a letter that I wrote that went out with all the casting submissions from our casting director, Cathy Sandrich Gelfond. It was basically a mission statement of what and who we were looking for: performers with theater backgrounds who are used to physicalizing their performances and working in an ensemble. We need you to check your ego and bring your creativity and try to buy into something really unique. Everybody answered the call.

RSG: We had the same conversation with our background artists, because many of them spend the entire 15 hours in a bed, and they had to commit to it. And people were really into it. There were people we were worried about: There was one woman who played a jaundiced patient, and she was yellow every day; we weren't certain if it would all come off when we finished.

NW: We have a "No phones on set" policy that goes for everybody. So, we have a lending library; everybody can grab a book. And they went through so many books. The [background artist playing a] pregnant woman would keep one in her belly when we were shooting, and suddenly she'd pull out a big Harry Potter book.

John, you directed the first episode. What were the decisions you all made about the tone?

JW: We couldn't go to all of this trouble to set it up this way and then not honor the feeling that you're just following these physicians and nurses through their day. We have a wonderful cinematographer, [Johanna Coelho], and the set is basically pre-lit with 246 separate zones that are all controlled on a computer so we can change the color temperature for different actors' faces. They move through the set as we rehearse and figure out how that's actually going to work. So, all of those considerations — about how to make it feel as if you've stepped into this real hospital — that was a lot of what we talked about directorially. Appreciating the patients in the same way the physicians do — they're looking at the patient for what they need to assess and how they're going to be treated, not for a melodramatic storyline.

We use handheld rigs, and we don't do any marks. The actors organically fall into the scene, and it's expected that the camera is going to figure out where they're going to be and follow them. Which was great with the younger actors, who hadn't done a lot before. If we'd been sticking marks everywhere, it would have been a nightmare.

You also have no music.

RSG: We knew we were going to do that from day one.

JW: The idea is that you're having the same experience [as the characters], so as soon as we attempt to sweeten it in some way by telling you how to feel, or telling you that there's a lot of pressure, we're actually removing the audience from the experience of the physicians and the nurses.

You guys have known each other for decades. With all that history, how do you work together?

NW: We've known each other a very long time, and we've worked together a lot before, but I have not worked with these men in this capacity before. I was a cast member on ER, and while we were extremely collegial, we [actors] were not part of the architecture of how the show got made. We had the set, and they had the offices, and they were separate cultures. I've been extremely gratified to be on the creative floor of this endeavor and watch how the sausage gets made and participate and learn how they made the other show, and this one, too, in real time.

Noah, was there a moment that you felt yourself dropping into your character?

NW: I don't know that an actor will ever get an opportunity to put on a costume and have the muscle memory have such resonance. It was really uncanny to me how familiar things were in a wonderful kind of way, like playing a musical instrument, then not playing for 15 years, and then finding that, while there's rust, there's something different about the tone that makes it more interesting now.

In terms of the character, he's defined by the characters around him. He's such a closed-off guy — intentionally so. He's got all of his compartments sealed tight out of necessity, and over the course of the season, we watch each one overflow into the next until he reaches capacity.

RSG: I'm lucky, because a lot of times you're writing characters, you don't know who's going to play them, whereas here I was writing to Noah essentially, with his feedback. You don't get to do that very often.

So many little details stand out: Dr. Robby has no time to go to the bathroom; Dana [Katherine LaNasa], the charge nurse, who obviously knows better, takes a cigarette break; and the Filipina nurses dish to each other in Tagalog.

NW: I'd like to highlight Dr. Joe again, because part of the writing time was Joe facilitating meetings with nurses from various hospitals, Pittsburgh physicians, people working with social services, Black women doctors talking about the experience of being a Black woman doctor in Pittsburgh. We drilled them on specifics, to try to find out: What is it you haven't seen on TV that is something that means a lot to you? What would make people cheer in your office if you saw that on TV? Everybody was really gracious and excited to share, and hopeful that we were going to make good on that promise. I think those are the details that give the texture and authenticity.

And how far ahead from this shift are you setting season two?

[They laugh.]

RSG: Not a clue.

The Pitt is now streaming on Max.

This article originally appeared in emmy Magazine, issue #2, 2025, under the title "Trauma Bond."