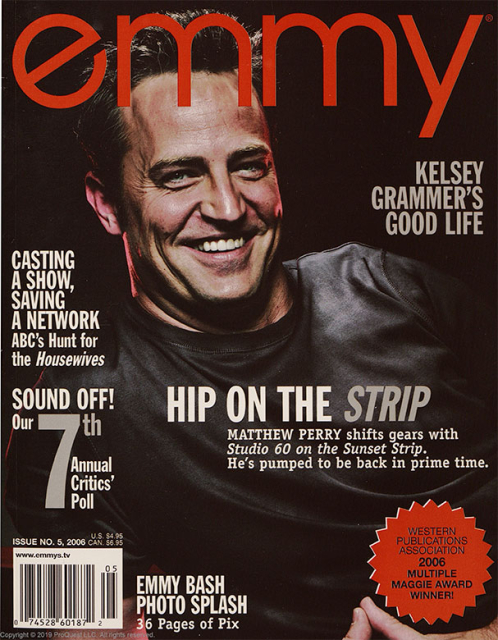

Like metal filings to a magnet, irony just seems to find some comic actors, no matter the situation. During a break from shooting NBC's new series about the inner workings of a comedy show, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, Matthew Perry — who, among a cast of gifted laugh-getters on Friends, was in his own zinger-slinging league — is sitting in the fake green room of the show's massive backstage set on the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank. He is describing his character, Hollywood writer Matt Albie, and going unspoken is the fact that Perry — though once again in the role of a caustic wit — is relishing the chance to play someone far removed from insecure jokester Chandler Bing

"He's a very ethical guy, pretty emotional, kind of messed up, and he's a real man," Perry says, his voice serious but excited. "That's what I like about it. He's an adult."

From the closed door, a knock-knock-knock, then a rumpled production assistant enters the room, Perry's lunch in hand. With sitcom timing, the actor blurts out, "And having said that, here's my peanut butter sandwich!" Perry laughs, and gazing at his diagonally cut, whole-wheat kiddie-menu entrée adds, "Yeah!"

Of course, no one would believe that a thirty-seven-year-old mega-millionaire couldn't slap two Jif-smeared pieces of bread together himself, but this hard-working actor is squeezing an interview into a hectic shooting day. Still, he recognizes the irony of a star-treatment moment.

Isn't this what made Perry a primetime treasure on Friends? That there wasn't an ounce of embarrassment, sarcasm or wise-ass charm that he didn't find in Chandler? And now that he's sinking his teeth into a character — created by Aaron Sorkin, no less — who gets paid to be funny, we may finally get a serious portrait of the peculiar mixture of darkness, wit and idealism that goes into the business of comedy.

At least that's what Perry hopes.

"I think broken or bent characters in drama, especially these days, are the most interesting, have the most colors," he says. "I don't think anybody wants to see somebody who's doing fine. In real life, that's great. But in TV, and especially on Studio 60, it's not the most interesting way to go."

Thomas Schlamme, executive producer (with Sorkin) and director of Studio 60, sees Perry moving beyond his ingrained gift for the rhythms of comedy into something deeper.

"On Friends the laugh was king, and you had to honor that king, but that's not always true here," Schlamme says. "Matt Albie is a writer who lives with a white piece of paper once every week and has to turn it into something, and that frightens the hell out of him. As an actor, Matthew is incredibly unafraid to explore that darkness, but he also knows as a comedian that it doesn't necessarily step on his comedy. That's a very rare trait."

Still, Perry's getting used to the idea of a non-sitcom, one-hour-drama table read. "At Friends, if you didn't get a laugh, you were kind of sweating," he says. "Here, you're supposed to get a laugh sometimes, but for the most part it's pretty serious, so that's an adjustment. I'll think, 'Well, I guess that didn't work, 'cause nobody made any noise.' You have to trust your instincts, as opposed to knowing that an audience is laughing."

PERRY REMEMBERS THE DAY AFTER the final Friends shoot in 2004 as encompassing every emotion. "It was sort of scary, it was a relief, a nice feeling of accomplishment at a job well done, and then this kind of blank canvas about the future, which was scary and exciting all at the same time." No longer a sextet banded together by contractual or cultural necessity — though personally close enough to remain lifelong chums — the cast members shot off in different directions after the finale. Jennifer Aniston concentrated on movies; Courteney Cox Arquette nurtured her production company; Lisa Kudrow executive produced and starred in the HBO series The Comeback; Matt LeBlanc carried the Friends spinoff Joey; David Schwimmer returned to the stage in London and New York. Only Perry seemed to recede from the limelight, not immediately taking on another series, feature film or other project.

"It's an almost impossible task to come off Friends," he explains. "You'd be hard-pressed to do anything that would have that much appeal and that huge an audience. And I wanted to change it up a little bit. Work-wise, it was difficult to find things." Mainly, he acknowledges, he focused on himself: some travel, time with friends and family. "It was a great time of personal growth for me. I wasn't working, so I had some time to kind of grow up," says Perry, who is single. What did he learn about himself in his enforced sojourn? He smiles and clams up. "Well, that's what I'm not going to tell you. That's the personal stuff."

So maybe one thing he figured out about his life is that when you have a chance to keep something private — unlike the much reported episodes of addiction to alcohol and prescription drugs, health issues and rehab stays that made Perry a tabloid fixture through his Friends years — you keep it private. In that light, his decision to play Albie — rather than some role crafted for him that might be hyped as "Matthew Perry IS..." — seems, in more than one way, a mark of maturity. One senses he'd rather bring his considerable energies to bear playing "a broken guy" — as he calls Albie — instead of being one off camera.

So when he describes himself as "doomed," for instance, he's talking about that snowball effect of actorly desire when a juicy part announces itself. That happened last October, when Perry read Sorkin's pilot script about the personalities assigned to revive the fortunes of a late-night network sketch series.

"I was in New York," he recalls, "shooting The Ron Clark Story," the recent TNT movie about a real-life teacher in Harlem that had, at that point, been the only post-Friends script to speak to him. "I read it on a computer in the business center of the hotel at 2 in the morning. By 3:30 I was pretty doomed in that I really wanted to do it, and I didn't want anybody else to do it. Actors follow good writing, and this was great writing, a great character and a great pedigree."

Perry's bona fides with Sorkin go back to his guest appearances on NBC's The West Wing as associate White House counsel Joe Quincy, a role that netted Perry two Emmy nominations (one more than he got playing Chandler), and with Schlamme even further back, to episodes of Friends that Schlamme directed in the second season. The West Wing connection also means Perry was familiar with actor Bradley Whitford, who on Studio 60 plays Albie's close pal, colleague and us-versus-them ally in the fight for art over commerce, Danny Tripp. "Brad and I instantly had this chemistry where it looks like these guys have been working together and been friends for a long time," Perry says. "We're having a lot of fun."

Today, dressed in the TV scribe's uniform of T-shirt, overshirt, casual pants and sneakers, Perry has been filming the fourth episode, which means that he and the creators are still working out who Matt Albie is. ("We just figured out his manic writing style," Perry offers, "and that when he watches sketches he mouths the words. That's this morning.")

Talking so early in the run of a show — especially one saddled with enormous, early buzz — lends a certain skittishness to Perry's answers about his character. But he's comfortable hinting that Studio 60, while ostensibly about the pressures of live television, will depend — as The West Wing did — on the depth of the characters, which include a smart, risk-taking network president played by Amanda Peet, a stern corporate boss played by Steven Weber and a conservative Christian actress — and ex-girlfriend of Albie's — played by Sarah Paulson.

Says Perry: "Even Aaron would agree that for the show to be able to sustain itself, you could do an episode where you don't even deal with the live show — where the people are locked in an elevator — and it's still interesting because we've created good characters."

Has he had to suppress the smirk-laden Chandler mannerisms and tics that became second nature during Friends' ten-year run? Perry says that avoiding those kind of winking, look-at-me sitcom theatrics has been foremost in his mind. "I tell directors that if they see any of Chandler, just tell me and we'll stop," he says. "It came up a lot when I was doing Ron Clark."

Clark is a naturally enthusiastic teacher with a goofball streak when it comes to getting kids' attention and steering it toward learning, but Perry admits he would overdo trying to be funny. "[Director] Randa [Haines] was like, 'No, no, no, keep it real.' She was a good Chandler policeman. But my guard is up for it here, so I don't have to be reminded too much. We were shooting something where two people kind of creep up on me and say my name, and my tendency is to do a huge scare take, like a W.C. Fields take, you know? And I'm just not going to do that, because it's too reminiscent of what Chandler would do."

GROWING UP IN OTTAWA, CANADA, Perry was the class clown who could barely muster interest in schoolwork. ("There are some teachers probably laughing about me playing Ron Clark," he says with a smile.) He sparked to acting after his mother, Suzanne Morrison, a former press secretary for Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, suggested he try out for the seventh-grade school play. His parents had divorced when he was an infant, and his dad, actor John Bennett Perry, lived in L.A.

Already smitten by how cool it was to occasionally see his dad on television in everything from Mannix or Falcon Crest to Old Spice commercials, Perry moved to L.A. at fifteen to try acting himself. "I thought — well, I still think — it's the only thing I can do," says Perry, who had ideas of a professional tennis career after making the Canadian nationals at thirteen, only to give that up a year later. "I wasn't good enough to afford a living at tennis. But when I was eighteen I did my first TV show, and I've been going ever since."

There was work — not necessarily the kind that gets you noticed — but it didn't stop him from assuming he was television's big talent. "I was on a Fox show called Second Chance when Fox was just starting. We were ranked ninety-third out of ninety-three shows, and I was walking around with an attitude," says Perry, laughing. "I was so young and stupid back then. I was nicer when I was on the number-one show."

And even as that instant-hit first season of Friends came to a close, the cast was still new enough that Perry and LeBlanc could be misidentified in a photo caption, as happened in a 1995 New York Times story. Now, he's the biggest name on Studio 60, and NBC is in nowhere near the ratings shape it was when the Central Perk clique acted as Thursday-night webbing to Mad About You and Seinfeld. One can imagine Perry feeling the pressure to hit a homer on his first post–Friends at bat. But he's not having any of it.

"I'm going to try to keep my head out of the game of trying to measure the success of the show," he says assuredly. "I was given the opportunity, for better or worse, of being on a very successful television show, with all the ups and downs in my personal life that came from that. So I'm not that invested necessarily in how well [Studio 60] does. I think it's more important for me to surround myself with — and feel surrounded by — people who want to do the best work. And if it's a huge success, great, 'cause we'll keep doing it."

Even if it means years of that special grind of fourteen-hour workdays and endless coverage shooting. But if anybody knows how to leaven the mood with a wiseacre quip, it's the guy who may have the best comic timing in the business. Schlamme recounts a recent instance when a long Friday shoot extended past midnight into Perry's Saturday birthday. Sure, a cake was brought out, but the moment was too perfect.

Says Schlamme: "He looked at me and went, 'Do you want me to blow out the candles eight different times so you can get eight different angles on this?'

This story previously appeared in emmy magazine issue #5, 2006.