Bob Hope was one of television’s earliest guinea pigs. In 1932, when the new medium was still a laboratory curiosity, Hope faced his first television camera on an experimental show CBS sponsored on its New York station W2XAB.

He was not impressed. He and two other actors had crowded together in front of a single camera. They had sweltered under banks of lights. Their images on the screen were dull, washed out, fuzzy. The signals flickered maddeningly. After the show ended, Hope wanted to forget the experience altogether. “Television’s a turkey,” one of the other actors declared. Hope did not disagree.

Eighteen years later, after he had triumphed on Broadway, conquered radio and the movies, and appeared on at least two other TV shows, Hope made what was called his official television debut in The Star Spangled Revue. The special aired live, Easter Sunday, 1950, on NBC. Thus, he became the first major film star to risk the wrath of the studios by hosting a television show. His debut, labeled historic precisely because it defied the studios, opened the television doors for other top movie stars to follow his lead.

But The Star Spangled Revue deeply disturbed Hope. Though the show garnered top ratings, its star hated his performance. He believed he didn’t yet know how to perform in front of the television camera.

In 1950, a lot of entertainers were just learning video techniques. Television was in its salad days. New York had been announced America’s TV capital. Network television was less than three years old, and another year would pass before the medium became linked coast to coast. It was a time of experimentation, even for a show business veteran such as Hope, who began to understand that television demanded a performance far different from that required in radio or movies.

“In radio I did everything fast,” Hope recalls. “I didn’t get anywhere until I started doing a very fast monologue. But in television I learned to take it easy and let the audience enjoy.”

Hope’s adjustments weren’t confined to his style. During his NBC debut, he had been distracted by constantly moving cameramen and technicians. For his second major television show, aired Mother’s Day, 1950, on the same network, he took control of the situation. “I asked them to stop moving,” he remembers, “It’s always distracting when someone is moving around. The eye goes directly to them. That goes for a movie set too.”

Thus, Hope and television began their long love affair, one that has lasted more than 37 years — through the early ‘50s laboratory period, past the so-called golden age of live programming, and into the taped era that has given the medium greater control over its product. Hope has seen the rise and fall of a score of home-screen trends and a bushel of TV stars. And still he remains, riding the airwaves with a tuxedo and a pocketful of jokes, even as he rode the boards all those years ago when he was struggling to make his name in show business.

Born Leslie Townes on May 29, 1903, in the London suburb of Eltham, Hope and his family emigrated to the United States when he was four years old. His stonemason father settled the family in Cleveland, and it was here, after flirting with a career as a prizefighter, young Hope decided he wanted to become a performer.

Quitting East High School when he was 16, he turned first to dancing. He teamed up with his sweetheart, Mildred Rosequist, who, as Hope saw it, danced better than Irene Castle. The Cleveland Castles danced together for a while, won a prize or two, earned a few bucks, and then broke up because Mama Rosequist didn’t trust Hope’s ability to make a living for her daughter.

Traveling the vaudeville circuit, Hope went through a series of male dancing partners, tapping, soft-shoeing, and singing his way from one town to the next for about three years. In 1927, he became a Broadway chorus boy in Sidewalks of New York before returning once again to vaudeville.

Because comedy was clearly his forte, Hope began to rise through the vaudeville ranks. In 1931, taking second billing to Bea Lillie, he played New York’s Palace Theatre, then the premier vaudeville house in the nation. The following year he appeared in his first important Broadway assignment, a revue called Ballyhoo of 1932. By 1933, after he opened in the Kern-Harbach musical comedy Roberta, Hope had become a star.

Other Broadway shows followed: Say When; Ziegfeld Follies of 1935, and Red, Hot and Blue! Then Hollywood called, and Hope, accompanied by his wife Dolores, traveled west on the Super Chief, arriving in Pasadena on Thursday, September 9, 1937, to make the Paramount movie The Big Broadcast of 1938. His first feature film proved to be a hit, partly because of the song Thanks for the Memory, the duet he performed with Shirley Ross. It eventually became his radio and television theme song.

At about the same time, Hope signed with NBC for his own radio program, The Pepsodent Show, which soon elevated him to the ranks of the nation’s top radio comedians. In her column on October 10, 1938, that great oracle of the silver screen, Louella Parsons, summed up the present and the future of Hollywood’s newest star when she wrote, “Bob Hope, scoring both on radio and in Big Broadcast, has been given a star dressing room at Paramount … ”

With his radio and movie careers nourishing each other, Hope tapped such celebrities as 18-year-old Judy Garland to work as regulars on his show and began shooting Road to Singapore, the first of the popular Road films, co-starring Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour.

With World War II, Hope’s popularity took off in another direction as he began the first of his famous USO tours. Beginning in 1941 and continuing throughout the war, Hope, dubbed “America’s Number One Soldier in Greasepaint” and “The GI’s Guy,” entertained military personnel in the South Pacific, Alaska, Europe, and North Africa.

After the war, the comedian found himself once again taking on the role of reluctant guinea pig in service to television. With an eye apparently cast toward the future, Paramount Pictures, Hope’s studio, had purchased a small experimental TV station housed on the studio’s lot at the corner of Melrose and Bronson. The station, whose call letters had been changed to KTLA, asked Hope to emcee what was to be the West’s first commercial telecast.

On the night of January 22, 1947, Hope surveyed the list of participating luminaries — Cecil B. de Mille, Dorothy Lamour, and William Bendix among them — then launched the historic telecast with the rapid-fire delivery he had learned from radio:

This is Bob “First Commercial Television Broadcast” Hope telling you gals who have tuned me in — and I wanna make this emphatic — if my face isn’t handsome and debonair, it isn’t me — it’s the static. … Well, here I am on the air for Lincoln automobiles. But I find television’s a little different than radio. When I went on the air for Elgin, they gave me a watch. When I went on the air for Silver Theater, they gave me a set of silver. Tonight I’m on for Lincoln, and they gave me this. (He holds up a Lincoln penny.) If you don’t get it, don’t knock it — this is an experimental program!

But Hope hadn’t enjoyed this 1947 experiment any more than his 1932 experience with TV. After he and the other entertainers began wilting under the relentless glare of lights, Hope told the station’s executives, “I don’t know where you’re going to find performers who will undergo this heat.”

But another kind of heat was about to overtake Hollywood’s performers. In 1948, as the nation took television into its living rooms, the leading cities reported a marked decline in movie attendance. According to media scholar Erik Bamouw, “Television had briefly drawn people to taverns, but now home sets kept them home. Radio listening was off in television cities; the Bob Hope rating dropped from 23.8 in 1949 to 12.7 in 1951 and continued downward.”

Hope didn’t need the weatherman to tell him which way the wind was blowing. In 1949, he performed an eight-minute monologue (“For nothing,” he recalls) on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town. The following year he made his well-publicized television “debut,” a 90-minute show with an extravagant budget.

But Hope was not winning any popularity contests among studio executives by appearing on television. “The reason I went into television was that NBC made me such a wonderful deal,” he recalls. "I was making a lot of money doing pictures and radio and making personal appearances. But it got so I was giving it all back to the government. I wanted a contract that would give me future financial security, and television came up with it. When I called Paramount to say I was going over to television, I asked if they could match [NBC’s] offer. They said they couldn’t. Suddenly I started getting threats from the exhibitors, saying it was all washed up. Then the television people and the movie people found out they could sell each other’s product. After that, there was kissing and dancing in the streets."

After Hope committed himself to television, he became one of the medium’s most ubiquitous performers. In 1952, he hosted TV’s first fundraiser, since called a telethon, to support the 333-member U.S. Olympic team’s journey to Helsinki. Later that year he served as one of NBC’s television commentators at the Republican and Democratic conventions in Chicago. And later still, during the same year, he launched the first of his once-a-month appearances as host on NBC’s Toast of the Town.

Hope made entertainment history on March 19, 1953, when he presided over the marriage between television and the movies at the 25th annual motion picture Academy Awards. Because several studios, including Warner Bros., Columbia, and Universal, had refused to help underwrite Oscar’s expenses that year, NBC placed a $100,000 bid, secured the radio and television rights to the ceremony, and thereby made the marriage possible.

Hosting the Oscar show for the seventh time that night, Hope was appropriately biting:

Everyone said that television and the movies would finally get together, and it finally happened. Tonight, you’re watching the wedding. The only thing you couldn’t see was the shotgun. … What a marriage! Now the question is: Which one wears the nightgown?

Hope went on to host many more televised Oscar nights, just as he went on to produce numerous top-rated specials. Some of those specials graced NBC’s Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theater, an unusual series that varied its weekly offerings with comedy shows and dramatic anthologies, some of which starred Hope. His Chrysler show was telecast between October 4, 1963, and September 6, 1967.

It is the Hope special, however, that has earned him his extraordinary place in American television. Through the years, such specials have included the celebrated Christmas shows (especially those aired during the Vietnam War), in which he entertained overseas American troops; the memorable Moscow show that won the distinguished Peabody Award in 1958; his first Texaco show, A Quarter-Century of Bob Hope on Television, with Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, and John Wayne, in 1975; and that endearing memorial to Crosby, On the Road With Bing, in 1977.

On May 27, 1981, when Hope’s 30-year Nielsen national audience ratings were published in Variety, the comedian was declared television’s all-time champion, a performer who had garnered “an unparalleled record of ratings achievement.”

Bob Hope came to the medium when it was in its earliest stages of development. He remained to help shape it. He learned to respect it, thereby giving television some of its most memorable hours. In the process he became one of its greatest stars. Thanks for the memory.

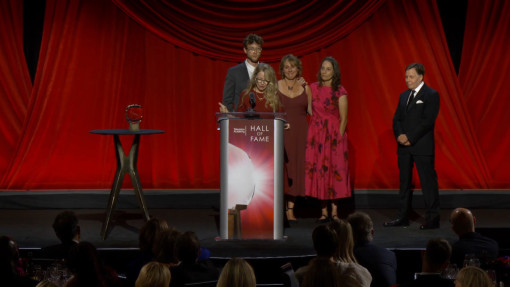

This tribute originally appeared in the Television Academy Hall of Fame program celebrating Bob Hope's induction in 1987.