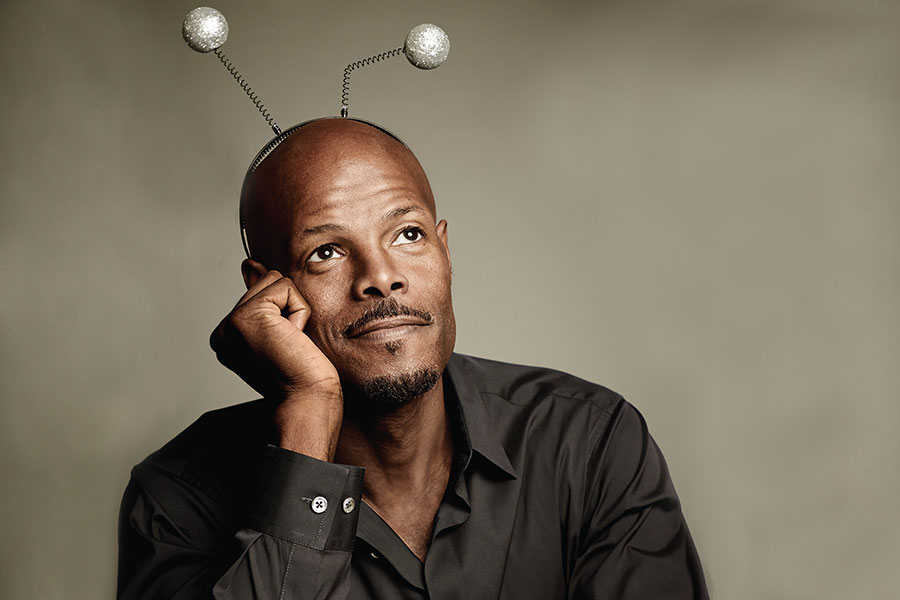

As a child growing up in the New York City projects, Keenen Ivory Wayans looked to his nine brothers and sisters for comfort, camaraderie — and always a chuckle or two.

His father, a devout follower of Jehovah’s Witnesses, managed a grocery store; his mother was a social worker. Money was tight, but the family pulled together to get by. “We grew up in a big household,” his brother Shawn has said, “and we grew up poor. So we spent a lot of time just trying to make each other laugh. All we had were laughs.”

Like many of his siblings, Keenen had a talent for comedy — even as a child, he knew he wanted to be a comedian. He realized it one day when he turned on the TV rather than go outside and confront a neighborhood bully.

On the screen, he saw stand-up comedian Richard Pryor, performing on The Dinah Shore Show. “He was doing a routine about the school bully,” Wayans says. “It was all the things I had just experienced. I was so amazed he could take this horrible moment and make it funny.” He was hooked.

Two decades later, Wayans and his younger brother Damon would create one of television’s most memorably outrageous shows, Fox’s In Living Color. It would not only feature many of his talented siblings, but also introduce such performers as Jim Carrey, Jamie Foxx and David Alan Grier.

Wayans was interviewed in July 2013 by Amy Harrington for the Television Academy Foundation’s Archive of American Television. The following is an edited excerpt of that interview; the entire interview can be viewed here at EmmyTVLegends.org.

Q: You grew up in a large family….

A: Five boys, five girls. The boys are Dwayne, me, Damon, Marlon, Shawn. And the girls are Diedra, Kim, Elvira, Nadia and Vonnie.

Q: Were you all creative as kids?

A: Not in the show-biz sense. We were creative in the survival sense. That’s what gave us a point of view that we’ve carried throughout life. When you have ten people in an apartment in the projects and a breadwinner who’s not winning much bread, it is a constant, creative way of surviving.

We all had jobs when we were very young. Whether it was shining shoes or collecting bottles or delivering groceries, we were always trying to find that way to survive. It was always legit.

My parents had very high moral standards. My mom refused to go on welfare, and we never sold stolen goods. Mom would say, “Because you’re of the ghetto doesn’t mean you are ghetto.” Both of them set a bar for us. But the hustle was always there as well. As long as it was legal, it was cool.

Q: Did working together when you were kids lead to your working together later?

A: We were forced to bond more than most families. Beyond just being poor, we were part of an experiment.

The city of New York started integrated public housing around the 1960s. My projects were comprised of Puerto Ricans who were brought in from the east side, blacks from Harlem and Irish from Hell’s Kitchen. You had three of the toughest groups — who had never related to each other — put into this eight-square-block housing development.

It was hell. Every single day you fought. But we fought as ten, and if one of us had a fight, nine of us were there. It really bonded us.

Q: Did you perform as a kid in school?

A: I didn’t. People who knew me would say, “I never thought this guy would be a comedian.” But the people who really knew me knew that that was the only thing I could ever be.

In big groups, I was always very shy and quiet. With my friends, I was the life of the party.

Q: What did you do after high school?

A: I took a year off. I didn’t know how to pursue being a stand-up comedian. But I had decent grades, so I went to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

I was one of the few kids from New York, and at lunchtime I was the entertainment. I would do my characters and jokes and I’d have everybody laughing.

One day, an upperclassman from New York said, “Hey, man, when you go home you should check out The Improv. It’s a comedy club. Richard Pryor started there.” That’s all he had to say.

The irony was, it took me going 2,000 miles away to find out about a club that was one mile from my house. I went to The Improv and I auditioned. It was like I had stepped into my dream.

Q: How did you build your career?

A: The Improv was where I was born. My comedy family was there. Chris Albrecht, who went on to head HBO and now runs Starz, was a manager there and he was sort of a mentor to me. He taught me little things about stand-up.

“When you go on stage,” Chris said, “I want you to say ‘I’ and ‘my.’ Never say ‘yours’ and ‘ours.’ The more specific you are, the funnier you’re going to be.”

Q: Describe your act and the topics you covered….

A: To this day, my stand-up act pretty much is me. It’s my life, my experiences, my point of view — that’s what my act will always be.

Now I’m raising kids and have teenagers and have been divorced. Your life just keeps giving you jokes.

Q: How did your work as a stand-up lead you to Los Angeles?

A: Chris Albrecht was hired by ICM, and he took five comedians with him as clients. I was one.

Q: In 1982 you appeared on the first episode of Cheers….

A: I had the first line on the first episode: “Those are our drinks.” I remember how nervous Ted Danson and Shelley Long were and how supportive of each other they were. I remember the newness of it. That’s a great memory.

Q: A year later, you were on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson….

A: That was the greatest moment of my career. When I was starting out, the biggest thing was to be on The Tonight Show.

I remember being backstage when they were about to announce me. My heart was jumping out of my chest. I put my head down, and I said something out loud, a line from Risky Business — “Sometimes you’ve just got to say, What the f—k.”

I ran out and did my act, and it went great. The icing was the moment that every comic dreams about — when Johnny asks you to come sit. That moment was the highlight of my career. Everything after that was gravy.

Q: How did that affect your career moving forward?

A: It put me in a different class of comics, but it didn’t change my career. My career changed when Robert Townsend and I decided that we were going to make our own movies.

I always say that my ignorance was my gift. We didn’t know how to write a movie. We didn’t know anything. We just went with things we did know.

So to write, we would lay out pieces of clothing that represented the different characters. Then we’d set up a video camera and we’d improvise. Whenever we’d switch characters, we’d put on a hat or scarf. Then we would watch it, and the stuff we thought worked, we’d write down.

We didn’t have any money. We didn’t know how to budget a movie. We thought if we got a camera and some film, we could shoot a movie. We didn’t know about having a crew, lights — nothing.

Robert got a credit card in the mail, and it said he could have a $5,000 limit. So he applied for ten other credit cards, and we used them to finance our first movie, Hollywood Shuffle.

Q: How did In Living Color come about?

A: It came about after the success of the film I’m Gonna Git You Sucka [which Wayans wrote and directed]. I got a call for a meeting at Fox, not in the film department, but the TV department.

They said, “Look, we’ve got this new network, and we really want to push the edge. We would love for you to create something for us. You can do whatever you want. You have total freedom.”

I went back and pitched In Living Color. I pitched the sketches “Wrath of Farrakhan,” “The Homeboy Shopping Network” and “Men on Film” [featuring Damon Wayans and David Grier as gay movie critics]. They agreed to make it a show.

Q: How did they react to the skits?

A: [Then Fox chairman and CEO] Barry Diller was horrified. I said, “Have him come down to the set.” I think one of the things he was worried about was whether gay people would be offended. That’s why I invited him to the set.

He stood off on the side and watched the “Men on Film” sketch. When the guys started going and Barry heard the audience, it wasn’t just laughter — people were stomping their feet. Then he started laughing. When they were done, he threw up his hands and left.

But when it came time to air it, everybody got nervous.

Peter Chernin, who was head of the network, sat me down and said, “Undoubtedly it is great and funny, but we just don’t think we can air this. I’d like to take out the following sketches — ‘The Homeboy Shopping Network,’ ‘Men on Film’ and ‘Wrath of Farrakhan.’ I’d like to air a tamer version, and when we build an audience, then we can push the boundaries.”

Q: What was your reaction?

A: I said, “I don’t want to do that. I want to kick the door in, guns blazing. If they like it, they like it. If they don’t, I’m good with that. I don’t want to trick the audience. I want them to know what we’re doing.” And they aired it. The rest is history.

Q: Describe “Wrath of Farrakhan.”

A: That was one of the smartest sketches we ever did. Basically it was a parody of Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan. But in ours, Minister Farrakhan beams aboard the Enterprise and creates racial dissension among all ethnic groups and points out how Captain Kirk has been exploiting everybody on the starship. It was just the right mix of everything.

Q: What was your inspiration for a sketch comedy show?

A: I auditioned for Saturday Night Live and didn’t get it. Damon was on Saturday Night Live and got fired. So I thought, I’ll create my own show. I knew all of these incredibly funny people who hadn’t been given a shot.

Q: How did you go about casting?

A: The casting was really fun. It involved a lot of the people I knew from doing stand-up in the clubs. I put them all through the process — they read the script and performed. Then they did improvs. Then, if they made it to the finals, they had to do their act on stage.

I needed people who could think on their feet, who could act and do characters — not necessarily do impressions, but mimic.

There were people who went on to become very famous who auditioned but didn’t make it, like Chris Rock and Martin Lawrence. But the people I did find included Jim Carrey, Jamie Foxx, Tommy Davidson and David Alan Grier, my brother Damon….

Q: What was it like in the writers’ room?

A: It was fun for most and sad for others. There were some very strong voices in there. This was pre–sexual harassment, so if you were a female writer, you really had to hold your own. It was very much a male-dominated business. The female writers put up with a lot of shit and got very tough very quick.

But it was an interesting mix of people, young and smart and funny. I made it very clear that they didn’t have to write black. They had to write funny.

Q: How much of your day was spent dealing with censorship?

A: Most of my week was spent on that. We had several approaches with the censor. The advantage we had was the slang. We knew there were things that we could say that he had no idea what they meant — we would get away with murder.

In the sketch “Hey, Mon,” we were cursing in Jamaican slang. It was just gibberish to him.

The best one ever was, we had this sketch and he said we couldn’t say this particular thing. So then we asked, “Can we say, ‘toss my salad’?” In slang, “toss my salad” literally meant “lick my ass.” He said sure. After that sketch aired he said, “How could you do that to me!” We used to torture the guy.

Q: You left the show in season four. Why?

A: Fox started something now commonplace. Up until that time, a show had its run for five years and then went into syndication.

But Fox started to strip the show before we got into syndication. From my point of view, that was going to kill syndication, which from a business standpoint is why you do the show in the first place.

It was very disheartening. I think if I had better advice or representation, I could have found a middle ground. But I didn’t and I decided to leave.

Q: Did you watch the show after you left?

A: Never.

Q: What do you believe is the show’s legacy?

A: Beyond all the great talent that came out of it, I think the legacy is being part of the progression of television, in the same way that All in the Family and Cosby and Seinfeld were — shows that had a different point of view that brought people of all races together, to experience something collectively. And the fact that you permeate pop culture is something that doesn’t happen often.

Q: How do you make comedy that other people can relate to?

A: I’ve always said that comedy is pain disguised as laughter. If you’re laughing about something, it makes it okay for others to laugh about it.

Comedians can take their pain and retell it and point out everything that was funny about it — that’s their art.

Q: In 1991 you participated in the TV special A Party for Richard Pryor.

A: My speech to Richard Pryor was everything I wanted to say to him. If I were going to bookend my career, it would be with my appearance on The Tonight Show and my appearance here, being able to thank the guy who showed me what I was going to do with my life.

I could not have been more open and sincere and loving and appreciative.

Q: How do you think Richard Pryor influenced stand-up?

A: He made it a performance art. Prior to Pryor, most comics stood there and told jokes. Richard Pryor, George Carlin, Lenny Bruce changed that.

Pryor’s greatest influence was on all the African-American comedians who came after him. All of us are disciples.

We proudly acknowledge that Pryor came along at a time when he was part of a movement, where the voice of black America was getting louder. As a comedian, he had the loudest voice. He was fearless and he pushed the boundaries.

He was so honest and truthful about who he was that white people weren’t offended by him. He was able to do it on his terms, and that’s what was so inspiring. It wasn’t compromised, it wasn’t playing it safe. It was just keeping it real.

Q: What is your legacy in the entertainment industry?

A: My legacy is my family — showing the world what one family can achieve together. We came from extremely humble beginnings, from the projects of New York to Hollywood, together, still loving each other and still working together.

I don’t think I could achieve anything greater than that.