His writing would influence generations of young viewers, but for Norman Stiles, the path to 123 Sesame Street was hardly as simple as a, b, c.

At New York’s Hunter College he studied zoology and chemistry, but out in the job market he was hired as a social worker. It wasn’t a line of work that offered a lot of laughs, but he nonetheless got his start there as a comedy writer, slipping jokes to a friend who knew some stand-up comedians.

Before long, Stiles would leave the trenches of social work and move into jobs writing for entertainers like Merv Griffin and Marty Brill.

In 1970 his career would take another turn when he was hired to write for the fledgling Sesame Street, which had premiered the year before. “It wasn’t the kind of writers’ room you typically think of, where all the writers are sitting around coming up with ideas,” Stiles says. “They would hand us a sheet that had the curriculum for the particular show that you were writing.”

Concepts for the show — created by Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett — centered around the letter and number of the day as well as basic cognitive learning skills. And thanks to the cast of colorful, lovable puppets created by Jim Henson, the show presented its lessons in fun and novel ways.

Stiles, who has won Daytime Emmys for both Sesame Street and the children’s show Between the Lions, would serve as Sesame Street’s head writer for many years. During that time, he and his staff would create some of show’s most iconic characters (“It is I, the Count!”) and stories. (This fall Sesame Street, in its 46th season, moved from PBS to HBO; airings will follow on PBS after a nine-month window.)

Stiles was interviewed in 2014 for the Television Academy Foundation’s Archive of American Television by producer Adrienne Faillace. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation; the entire interview may be screened at TelevisionAcademy.com/ archive.

Q: What was your first professional writing gig?

A: While I was working at the welfare department, a friend at another office met somebody who was writing jokes for comedians. In particular, Marty Allen and Steve Rossi. In their sketches, they did an interview — Marty would play a character and Steve would ask him questions.

My friend said, “They have a sketch they’re going to probably do on The Dean Martin Show, where Marty is a lion tamer and Steve is going to interview him. If you could write some questions and answers and jokes, I’ll give them to them. They pay $10 a joke.”

For me that was great. I smoked at the time and usually by the end of my pay period, I had no money to buy cigarettes. So I figured I just had to sell one joke and I’d be able to buy cigarettes.

Q: How did you get your foot in the door at Sesame Street?

A: One day I was watching TV and saw Sesame Street. I saw that they had writers, and it was the only gig in town except for Johnny Carson’s show — and I really didn’t think I could get that job. I didn’t have a hell of a lot of confidence in myself as a writer.

I called up, finally located [head writer] Jeff Moss. He actually answered the phone, and I said, “I’d like to try out.” He said, “Watch the show; write some sketches. I’ll look at them and we’ll go from there.”

So I did and he said, “These are the best sketches I’ve seen since my own. Write some more.” I wrote a few more. He said, “These are terrible. Now we’re going to rewrite the first ones.”

Q: What was that initial group of writers like?

A: It wasn’t a typical writers’ room, where all the writers are sitting around coming up with ideas. They would hand us a sheet that had the curriculum for a particular show. Sesame Street had a huge curriculum.

They would select the letter of the day, the number, and part of the show was filled with animation and live-action films and puppet pieces. Whatever was left over was your job to fill. You got that sheet, you went home and wrote your show, and then turned it in to Jeff.

Q: How would you describe Jeff?

A: Jeff was a man of few words, a wonderful guy. Funny. One of my experiences tells you a lot about him — I had no idea what to do in one particular script and I went to him a day before it was supposed to be turned in. I said, “Jeff, I don’t know what to do. I’m blocked.”

He said, “You have no ideas?”

I said, “I had ideas, but I didn’t like them.”

“Your job is not to judge the ideas. Your job is to write them. My job is to tell you whether they’re good or not. Go write.”

So that’s what I did. He opened me up by giving me permission to be bad.

Q: You were involved in creating a couple of the Muppet characters. Tell us about creating the Count.

A: With the Count, we were teaching counting. I was thinking of Count Dracula and it just sort of emerged. I remember [vice-president and creative director] Sharon Lerner walking by my office. I said, “What do you think about a Count Dracula character?”

We talked about it and I said, “Hello, I am the Count. They call me the Count because I love to count things. Let me count your neck” — instead of “bite your neck.” That’s how that started.

I wrote the first script and [director] Jon Stone said, “Great character, terrible script.” It had something to do with hot dogs. I don’t know what it was, but it was terrible.

Q: And Forgetful Jones?

A: One of the curriculum areas was cognitive function — you want to teach kids that remembering is important and that there are ways to remember something.

There was an old cowboy movie, something like Cowboy Jones , and I put the two of them together. The idea was that he was so forgetful that you could go through the steps [of remembering] with this character — but the kids would be ahead of him, which was a teaching tool. If the kids are a little bit ahead, they were going to be more engaged.

[Puppeteer] Richard Hunt was great with that character. He gave it so much of the personality, the goofiness. The idea was that he wasn’t terribly upset, and nobody was upset with him. You wanted kids to understand that everybody forgets, just like everybody makes mistakes.

Q: There have been so many guest stars on Sesame Street over the years. Do you have any favorites?

A: Ladysmith Black Mambazo [the South African male choral group that sang on Paul Simon’s Graceland]. Chris Cerf and I wrote [the song] “Put Down the Duckie” when Ladysmith and Paul Simon were at their height. They were coming to Sesame Street, so we asked, “Would you do this?” They said yes.

We didn’t know exactly how they were going to do it. Paul Simon did his version, and I’m in the studio with Ladysmith Black Mambazo. And they start to sing, “You have to put down the duckie, oh yeah ….” Chris and I got chills with that.

Q: Why did you leave Sesame Street in the mid-70s?

A: One of the Electric Company writers, John Boni, said he was going out to Los Angeles. He had a friend, Norman Steinberg, who had written Blazing Saddles with Mel [Brooks]. John was going to see what work he could drum up.

He said, “Let’s come up with another parody like Blazing Saddles, another historical parody that uses anachronistic humor.” So we came up with a TV parody of Robin Hood that we called Waiting for Richard.

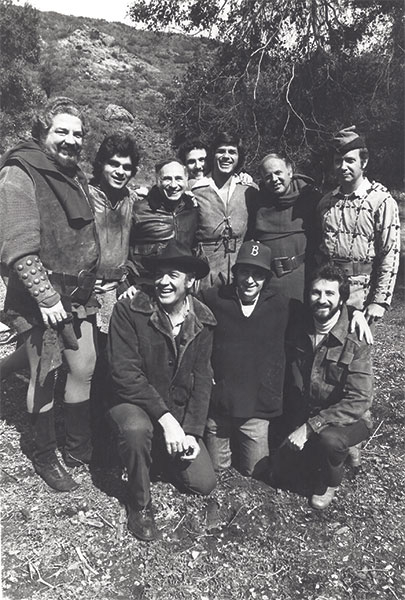

So John goes out to California and meets with Steinberg, who had become a development executive at Paramount. It was given to Mel and he said, “Yeah, I’ll get involved.” He’s the king of comedy at that point, so Paramount gave him a deal. We went out to California to work with Mel and Norman on the pilot [for ABC]. The name was changed to When Things Were Rotten .

Q: During your time in L.A., you also worked on Fernwood 2night and America 2night.

A: I loved working on those shows. I don’t know that anybody is aware that [writer- producer-performer] Alan Thicke was the brilliant mind behind the tone and everything about it. He had a complete understanding of what he wanted to do and what he wanted us to do. It was wonderful because we had such freedom.

What we were basically doing was taking the National Enquirer and all those [tabloid] papers and treating them like they were real news.

Q: But you went back to Sesame Street in 1980. Why?

A: I was losing my mind in Los Angeles. I didn’t think I was suited for the work. I went back to someplace safe. It wasn’t easy. You go to Hollywood — “I’m going to become famous and be a big success” — but when you then say, “I’m coming back to New York,” emotionally that’s hard. Fortunately, the producers at Sesame Street said they would have me back.

Q: Let’s talk about some of the notable episodes on Sesame Street while you were head writer. In 1983 you wrote one of the most iconic, “Farewell, Mr. Hooper.”

A: When Will Lee died [he had played Mr. Hooper, one of the four original human characters on Sesame Street, from 1969 until his death in 1982], we had a choice to make. We could have let it go and brought in another actor, or let the character just disappear. If we really wanted to tackle [the subject of death] on the show, what would we say?

The first thing was to talk to some people who knew the age group. We were told that the emotions and sense of loss that adults feel when somebody dies are different than what a [preschooler] feels.

So then you ask, “What’s important for a three-year old to know about death?” It’s the basics: when somebody dies, they don’t come back. Then kids might say, “But he did this and this for me.” Their reaction might be “I’m angry, I’m sad.”

Q: So how did you put together the pivotal segment when Big Bird learns that Mr. Hooper has died?

A: I kind of knew what the segment was going to be. But then I’d seen Carroll Spinney [who played Big Bird] do this move where he took Big Bird’s beak and put it between his legs so that the character appeared to be looking behind himself [upside down]. I wanted to do something where an adult sees him doing it. It’s the kind of thing that kids will do, and adults will say, “Why are you doing that?”

There’s no purpose necessarily — they’re trying something out.

Q: How did that relate to the death of Mr. Hooper?

A: I wrote this segment in which Gordon [Matt Robinson] sees Big Bird doing this and asks, “Why are you doing that?” Big Bird says, “I don’t know. Just because.”

I realized it would be a good way to tie in with the segment in which Big Bird learns that Mr. Hooper is gone, because we had to answer the question, “Why is he gone?” You really can’t answer that question. So I put those two things together. When Big Bird learns that Mr. Hooper is gone, he says, “Why does it have to be this way?” Gordon says to him, “Just because.”

Q: The episode also featured a baby at the end.

A: I wanted to bring birth into this discussion. At the end of the show, Big Bird is at his nest and in comes this woman with her recently born baby and Big Bird says, “You know what the nice thing is about new babies? Well, one day they’re not here, and the next day, here they are!” And with death it’s just the opposite — one minute, somebody’s here, and the next minute they’re not.

Q: The episode was awarded a Daytime Emmy and a Peabody. How does that make you feel?

A: Humble. I’m very proud of the show — the producers, the actors — for making the decision to do this. We were able to do it in a very simple, direct way. At the time, there were real tears for everyone, because in truth they were talking about Will Lee. I was really happy that we did it because of Will. It’s exactly the kind of thing he would have wanted.

Q: Do you have any favorite segments that you wrote during your time at Sesame Street?

A: We went through a series of stories with Snuffy. At first he started off as a character who was only real to Big Bird. We received input from people who were working with kids who were abused and they said, “You know, the adults in these children’s lives don’t believe them.” So having Snuffy as Big Bird’s imaginary friend — with no one believing him — was reinforcing that notion.

We discussed it and I said, “What if at first some of the grownups believe him? At least Big Bird would have somebody on his side who believes him, even though they haven’t seen Snuffy.”

There’s something that happens when the grownups are not all on the same page; there’s a difference of opinion, which is nice. Eventually we said, “Let’s just dispense with this and move on. It’s better that people believe him.” It was also good creatively because we could have Snuffy interacting with people. So I wrote the show in which he is finally seen, and I did so with great satisfaction.

Q: Big Bird has had quite an impact on generations of viewers.

A: I just saw the documentary I Am Big Bird. Wonderful. One of the stories they tell is when we got a call from NASA saying, “We might want to have Big Bird go up in the shuttle.”

From Big Bird’s point of view, which was in the documentary, he had to think about this: “Oh my goodness, the training! And what if something went wrong?” He finally said yes. But then NASA decided he was too big. So I was sitting with [show executive producer] Dulcy [Singer] and said, “What if we sent Radar — his teddy bear — up?”

Q: Did it happen?

A: I came up with this idea that the captain of the shuttle was having trouble sleeping in space, so NASA wanted to send Radar, to help him fall asleep. We would show the launch and he would be up in space, and we’d show Radar floating toward the captain; he would embrace Radar and fall asleep. But they said no.

Eventually it went all the way to the top of NASA — they decided instead to put a teacher on that flight. That was the Challenger flight that exploded. Can you imagine if we had done that? Big Bird would have been down there, and the flight would have taken off.... It would have been horrible. It’s horrible as it was. I’m sorry about the teacher [Christa McAuliffe]. But can you imagine?

Q: In 1995 you left Sesame Street for good. Why?

A: I’d reached a point where I didn’t like the way [Children’s Television] Workshop was going. I felt we were being pushed too much by merchandising and marketing.

Chris Cerf and I felt that there was room for a show for kids who were graduates of Sesame Street. And one of the areas of development that was near and dear to Chris’s heart was literacy. His father, Bennett Cerf, was head of Random House and his mother worked with Theodor Geisel — Dr. Seuss — on beginner books, so he had grown up in publishing and wanted to do something with beginning readers.

We came up with the idea of setting a [PBS Kids] show in a library and Chris came up with the pun, Between the Lions — the library lions — and the lion [puppets] would be the stars of the show; they would run the library with their cubs.

Q: What advice would you give an aspiring children’s television writer?

A: Watch what you like — what touches you — then write for that particular show when you’re starting out. Use the characters. Play with them. Have them talk to each other. But don’t try to be totally different. Start with what exists, especially if it’s going to be for television, because that’s where you’ll learn how to do it. You’ll learn to use the muscles that you will need to be able to create characters.

Q: What is the legacy of Sesame Street?

A: I don’t think there will ever be a children’s program that had the initial and continued impact that Sesame Street has had. Ever. And there will never be another Jim Henson.

There may be other great shows, but that moment in time — you had a country that was focused on helping children, Head Start [programs] were started, there was the war on poverty. You had the country focused on doing good and trying to help those who needed help.

Into that mix you had this television show, which tapped into the best talent available in television. All of these things came together.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 10, 2016