As a young actor starting out in the 1960s, Hector Elizondo opted not to change his name.

"Now it's fashionable to have an exotic name," he says, "but back then it wasn't." He has no regrets. As the decades have passed, the New York native — of Puerto Rican and Basque descent — has seen his name in the credits of more than 150 television productions, from an acclaimed episode of All in the Family in 1972 to the popular Last Man Standing, which ended its run just this year. Film and theater credits round out his long professional résumé.

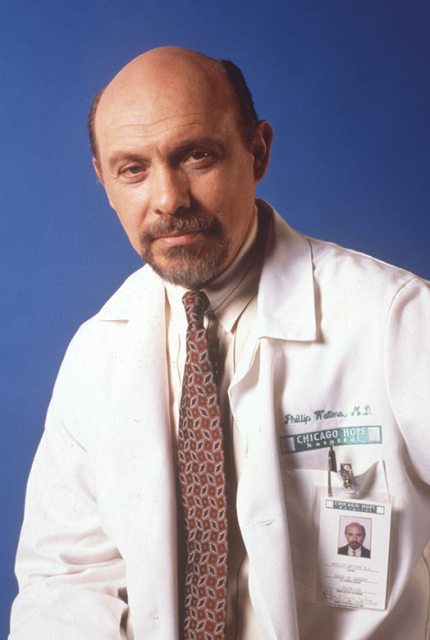

Elizondo won an Emmy in 1997 as outstanding supporting actor in a drama series for his portrayal of Dr. Phillip Watters on CBS's Chicago Hope. He was nominated four times for that role. Unfortunately, his winning moment included a sad omission: he forgot to thank Carolee Campbell, his wife since 1969. "What I remember more than anything else is, I should have included my dear wife," he says. "It was all a blur. I wish I could do that over again. It's one of my deep regrets in life, actually."

But even before he began turning heads on Chicago Hope, Elizondo was already Emmy-nominated — in 1992, for his supporting role in Mrs. Cage, an American Playhouse drama on PBS. Over the years, his recurring television gigs have ranged from USA's Monk to ABC's Grey's Anatomy. He also thrives on voiceover work, most recently playing Grandpa Beagle on Disney Junior's Mickey Mouse Mixed-Up Adventures.

Elizondo had a long, fruitful friendship with the late film producer-director Garry Marshall, resulting in roles in 18 of his films, including Pretty Woman and Runaway Bride.

Elizondo was interviewed in April 2015 by for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire interview can be screened at TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

Q: What was your path to acting?

A: Well, I tangentially rubbed against theater while I was the conga player for a jazz dance class. One day the choreographer said, "I need an adagio guy, somebody to move well and carry these skinny little people around." I got the job as the dancer, and I lost the job as the conga player. It was a very useful experience. I found out I didn't want to be a dancer.

But because of that I was introduced to theater — that's when I was affected. I said, "I don't know what they're doing or what's happening here, but I'd like to be part of this somehow."

Q: What did you like about it?

A: The immediacy. The response. The collective experience. Later on, as I studied and started to perform in repertory theater, I realized it was telling the story — one of the oldest things to do — that I liked. I was an intermediary between author and audience. I adored it.

Q: You started TV work in the late '60s, and in 1972 you appeared in the famous "Elevator Story" episode of All in the Family [in which Archie Bunker (Carroll O'Connor) gets stuck in an elevator with a Black attorney (Roscoe Lee Browne), a Puerto Rican janitor (Elizondo) and the janitor's very pregnant wife (Edith Diaz)].

A: That was a turning point. I knew All in the Family was groundbreaking, but I didn't know to what extent. People were laughing and discussing it around the water cooler. And I didn't know that the show's future depended on the success of that particular episode.

Q: Really?

A: Yeah. [Creator] Norman Lear had to convince Mr. O'Connor that the ending would work. Not only did it work, it made the show. You saw the humanity of Archie Bunker. How could this bigot be so well loved? Well, he did have a big heart. It was a wonderful experience.

Q: And at the end of the episode, your wife goes into labor in the elevator....

A: Yes, she gives birth. [The camera stays on Archie during the birth; he smiles when the newborn cries.] It was dynamite.

Q: In the '70s, you were also on two episodes of the cop drama Kojak.

A: Telly [Savalas] was terrific [as Lieutenant Theo Kojak]. He sucked on a lollipop; he took everything in stride. He loved what he was doing, and the camera loved him.

It's that ephemeral magic of a camera — you don't have to be pretty or handsome — but the camera either likes you or doesn't. And as an actor, you know how to use that, that's the craft. Long days. But what I learned from Telly was how to pass those days. Whatever he was doing, he made it look easy. It takes a lot of hard work to make it look easy, working 14 hours a day.

A little anecdote? The first episode I did, we were blocking and he said, "You gonna go like that?"

I said, "Like what?"

"You're not going to wear a 'dog'?"

He was talking about a toupee — I said, "Nah."

He said, "I'm the only coconut here. You got a dog?"

I said, "I got two or three dogs — I don't like wearing them." They had to send a production assistant to my apartment and bring back a toupee. I had to wear a damn toupee! It was pretty funny. So I learned, when you were with Telly, you've got to wear a dog.

Q: You did two episodes of The Rockford Files , as well. And you went on to work with James Garner many times in your career ....

A: What a gentleman! From him I learned how to comport myself on the set. He quietly mentored me. I miss him.

Q: Did you first meet him on Rockford?

A: Yes. He knew everything about the equipment, the cameras. He looked at me one day and said, "See that guy over there? The guy who's pacing back and forth with a cigarette in each hand? He's the director. You want to look like that? There's a lot of pressure in television. You don't want to direct."

Then he said, "You see that camera? I own that camera. See that truck? I own that truck." He owned all the equipment. They rented it from him. Cherokee Productions.

Q: Before long, you starred in your own CBS series, Popi ....

A: That was a precursor to lots of things, and [in 1975] it was a little ahead of the curve. My idealism bit me in the rump on that one. My character was a widower from Puerto Rico, working like crazy, three jobs — a working-class hero and single father of two boys. I said, "We have to give some kids a break here. Let's not look for professional kids." Oy, what a mistake.

The poor producer, he was such a nice man. He said okay, little knowing that I had given him a headache. We went on this talent search — CBS was kind enough to indulge me. I didn't know that idea was going to be a pain in the ass. We came up with two kids; I'm sure they're good citizens, but they weren't professionals.

Q: Popi was one of the first network shows with a Latino cast. What did you think of the storylines?

A: As I said, we were ahead of the curve. That's why I wanted it to be good. I worked very hard on it. It was a one-hour single camera. Long days, tough work. And even though we were getting millions of viewers, back then there were only three networks and Happy Days was getting more. So we lasted for 11 shows — that was it. And the irony is that Garry Marshall is now one of my best friends. [Marshall, the creator of Happy Days, died in 2016.]

Q: In 1984 you starred again in another series, a.k.a. Pablo.

A: Norman Lear — King Lear — called. Again, it was ahead of its time. And not conceived very well. It needed a little more time, a little more work.

Q: What was the premise?

A: Paul Rodriguez played an aspiring stand-up comic from a Mexican-American family. In retrospect, we gave it a shot. We worked hard. And I was forced to volunteer to direct three of them. That's how I got in the DGA. Mr. Lear was very persuasive.

Q: What was that experience like — especially after James Garner's advice?

A: Yeah, I cut back to Jim saying, "You want to look like him ?" No way. I was performing in the show. So I had to both direct and act. I wasn't ready for that. And Norman, he put his shoulder to the wheel, bless his heart. A man of great integrity and great courage and great vision.

Q: You played Paul's agent, José Sanchez/Shapiro.

A: Yes, I came up with the idea to make him a Cuban Jew. I gave him the name José Shapiro. And he wore a toupee — not that he was trying to pass as though he had hair. I said, "Let's have this guy wear a toupee that looks like a toupee. I'll get one that looks like a lid." And every once in a while, it's a little off and he fixes it. He has no vanity. I thought it was an interesting character choice. And Norman loved it.

Q: How do you feel about wearing toupees for roles?

A: My early acting teacher said, "You're lucky; you're going to get bald soon." I was a kid, I was 22! I said, "What are you talking about?" He said, "It's the best thing — you'll be able to play all sorts of roles."

He was right. But if you're shooting outdoors and the wind blows the wrong way, it's a problem for hair and makeup. Heaven help you if you don't have that stupid tape on, the thing will blow off and three grown men will run down the street chasing it.

Q: Let's move on to your role on Chicago Hope, the David E. Kelley medical drama that debuted in 1994....

A: We shot at Fox, and we had state-of-the-art equipment — it was quite a set. And we had doctors on set as technical advisors. After the [real] doctors would finish a scene, they'd hang out. They loved being background extras. We couldn't believe it. I said, "You guys have more degrees than a thermometer, and you're hanging around making believe you're making a phone call in the hallway!"

They were enthralled by the environment, the moving parts. These crews are teams of people who have their own language and they never get in each other's way. Something like an orchestra.

And we had a wonderful show. Hard, hard, hard work. Mandy Patinkin, Peter Berg... it was quite a cast. I was proud of that show, very proud.

Q: What was your experience working with David E. Kelley? He wrote a lot of those scripts himself.

A: Yes, in the beginning especially. We were always admiring of the work — the chances he took, the constant search for what makes people tick, the wrinkles of a personality. It was fascinating to be part of that, to be an intermediary between an audience and an author with that kind of genius.

Q: How would you describe your character, Dr. Phillip Watters?

A: He was the chief of staff, so he had a lot to do. Mainly he had to listen a lot. It was not difficult doing the character. What was difficult was the medical jargon. So we'd cheat sometimes. There would be little Post-Its we'd glance at. You had to do it, or else you wouldn't get through the day. You were always on your toes on that show. And we laughed a lot — in spite of the work. Because we knew the work was good.

Q: NBC was airing ER at the same time that CBS was airing Chicago Hope.

A: Oh yes. Programming choices — it's only everything, right? That was really a tragedy. I think we could have been a top show. But as it was, we did very well.

Do you remember Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? I don't know how many shows it knocked off the air. We were one of its victims. I'm sure we were an expensive show at that time. So we were gone.

Q: Did you have a favorite storyline for Dr. Watters?

A: The storyline about the death of my son, that was very hard. It got me the Emmy, though.

Q: That was "Bridge Over Troubled Watters"?

A: Yes. That was difficult because I'm a father. It was hard, but I went there. I said to myself, "That's in your arsenal as an actor." If you're going to be an actor, you're going to have a secret bag of stuff. You have to know how to use that and go there.

Q: What was it like, winning your Emmy?

A: It was a confusing thing. I'd been nominated twice before for the show [in 1995 and '96]. I didn't expect to win that one [in '97; he was nominated again in '98]. What I remember more than anything else is, I should have included my dear wife in my thanks. It was all a blur. I wish I could do that over again. It's one of my deep regrets in life, actually.

Q: You joined another medical series, Grey's Anatomy, in 2007 as Carlos Torres, the father of Callie (Sara Ramirez)....

A: The cast and crew had been there since 2005, so I entered the family as a guest. You're coming into a family unit from the outside — it's a little tricky. You have to know how to handle yourself. Luckily, most of the time when I walk onto a new set, I know a lot of the crew.

I looked at the character and thought, "What's his flaw?" He loves his daughter, though he has difficulty with her being a lesbian, to say the least. What's going to be interesting is this guy — who you think will never come around — comes around and becomes a champion. Now you've got an arc!

Q: And that was a recurring role for you.

A: Yes, and that was fine with me. Another recurring role — another wonderful one — was with Tony Shaloub in Monk. Not only is Tony a pro, he wants the show done as well as possible. He won't let anything slide. He's such an intelligent actor. It was always a pleasure to work with him.

Q: Before Monk, you were part of the ensemble of Cane, the Cynthia Cidre drama about a Cuban-American family in the sugarcane business....

A: I loved that show; it had a wonderful cast. We shot at Radford Studios in Studio City, and it was a terrific set. As soon as you got there, somebody came around with Cuban coffee and little Cuban sandwiches. So there was a great aroma. And in between takes we would be dancing, and there were a lot of laughs.

Jimmy Smits [who starred as Alex Vega] was a terrific captain. He cared deeply about that show. But then came the writers' strike. "Don't worry," we were told. "It's only going to be a couple of weeks — we'll keep the sets up." But it's expensive to keep sets up. Two weeks. Three weeks. Four weeks. It was three months of that. Lots of shows went down. Ours was one of them.

Q: Your character, Pancho Duque, was the head of the family....

A: He was another Phillip Watters — with a slight accent. He was an immigrant from Cuba. He had this incredible family, and keeping it together was Shakespearian. It was operatic, in a way. And then there was Jimmy Smits, who was the heir to it all. As an actor, I could see that you would salivate to do something with that nuanced side, that complexity. He was perfect.

Q: In 2011, you began playing Ed Alzate, the business partner to Tim Allen's character on the sitcom Last Man Standing. Had you worked with Tim Allen before?

A: No, I hadn't had the pleasure. Tim is a damn good actor. I don't think he's given enough credit. He is, of course, a very funny man. A very smart man. And he's done a lot of movies and television. He loves working.

Q: In film you've had a long association with Garry Marshall. How did you meet?

A: He saw me on stage, and then invited me to play basketball on his court — this was in 1979 or '80. At one point during a game I faked, did a behind-the-back pass, and the ball hit him right in the chops. He gets down on his knees and everybody stops. He coughs into his hands, checking to see if his teeth are in. "I'm all right," he said.

He told me, "You're a terrific actor but a lousy passer. Let's have a meeting. I think I got a movie for you." That was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Q: What is he like as a director?

A: If you're a visiting actor, the first thing he asks you is, "Did you eat?" Then he says, "Get him a sandwich." If you ask him, "What's the secret to directing?" he says, "Wear comfortable shoes and change them twice a day." He takes all the esoteric booga-booga out of it. He is a communicator. He has terrific comedic ideas.

When I asked him about my character in Pretty Woman, hotel manager Barnard Thompson, he said something brilliant. He said, "Play the guy that you'd like to work for," and he walked away. That was it. That's how he directs. If you need coaxing, he's there to coax you. He gives you a certain kind of confidence. It makes the day easy.

And the crew loves him. If it's your birthday you're going to get a birthday cake. And he loves parades. So during a movie, there's a parade. Every department has to compete against the others — there are judges and they give out ribbons. You wear funny hats. That's Garry Marshall. Someone once said, "Garry doesn't make a movie; Garry throws a movie."

Q: What is your proudest career achievement?

A: Without my knowing it and without my planning to, I've inspired some people who didn't think someone with an exotic name could be given an opportunity.

I didn't change my name — and it's quite exotic, compared to most American names. Now it's fashionable to have an exotic name, but back then it wasn't. But especially for the Latin-American community, the Hispanic community — I was the only Nuyorican starring on Broadway.

But I also remind them of something that's a little sensitive — I'm a white guy. If I had been mestizo — of any shade — I wouldn't have had those shots. Perhaps today, but back then, no. Also, I was theater-trained. I did repertory theater, I studied. No one ever gave me anything for free.

You have to put in the time, the sweat. Nowhere is it written that you're going to be successful. And I've reminded kids to redefine success. Just put one foot in front of the other. Remind yourself that it's a lot of hard work and be prepared when you're called.

Adrienne Faillace is the contributing editor for Foundation Interviews.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 8, 2021

For more stories celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month, click HERE