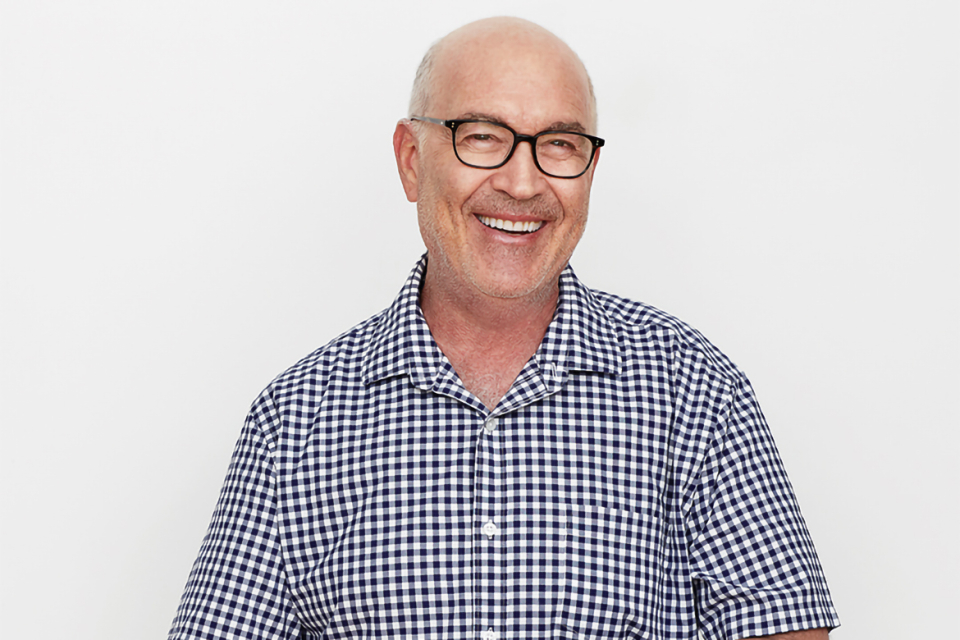

When the Emmy nominations were announced in 1992, Joshua Brand was surely smiling.

Northern Exposure, his CBS series about a young doctor (Rob Morrow) who moves to tiny Cicely, Alaska, to work off his medical school debt, received 16 nods. and his NBC series, I’ll Fly Away, about a black housekeeper (Regina Taylor) working for a white southern family during the civil rights era, received 15.

At the Emmys ceremony that fall, Brand personally took home two awards when Northern Exposure was named outstanding drama series and the pilot for I’ll Fly Away topped its writing category.

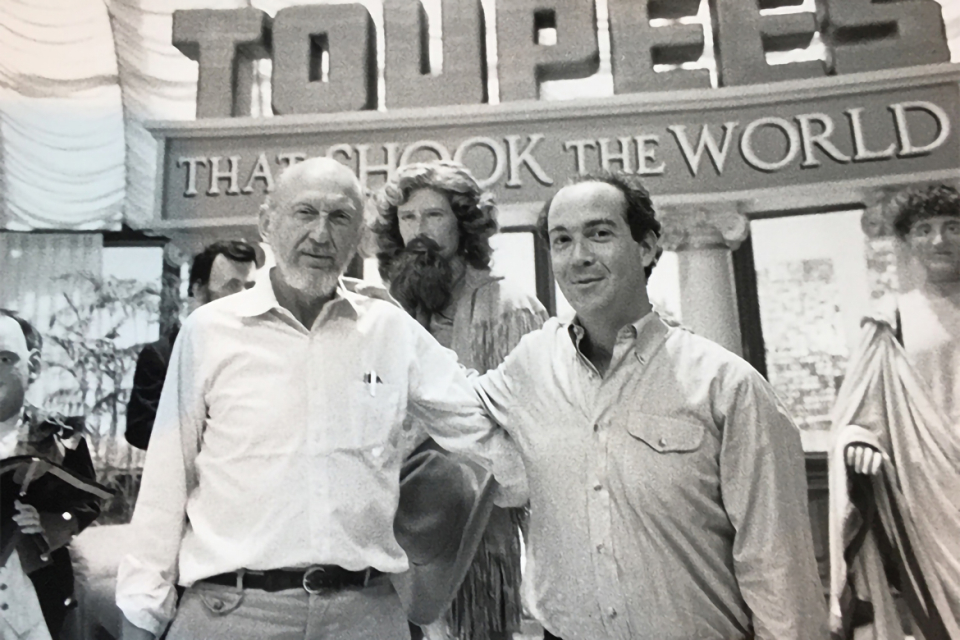

With his former producing partner John Falsey, Brand has collected three Emmys in all; the pair also won in 1987 when A Year in the Life — their NBC series about the challenges facing a Seattle family — took outstanding miniseries.

As a creator, writer, producer and director, Brand has told an array of stirring stories on television. Like Northern Exposure, his other early success, NBC’s St. Elsewhere — about interns at an overburdened Boston hospital — displayed a new creative style, marked by a previously unseen degree of emotional honesty. With unique characters and complex plotlines, Brand’s shows have never shied away from risk.

“I’m interested in seeing things that are different,” Brand says. “I’m interested in challenges.”

Originally from Queens, New York, Brand earned a master’s in English literature from Columbia University in 1974 and started writing for television not long after.

He cut his teeth on CBS’s The White Shadow, which starred Ken Howard as the basketball coach at an urban high school. Brand has earned 14 Emmy nominations, with his most recent work as a writer and consulting producer on FX’s The Americans earning him nods in 2015 and 2016.

Brand’s career in television has given him the opportunity to learn about others as well as himself. “I found out that there’s nothing in my life that I like more than taking an idea and seeing if you can turn it into something,” he says.

Brand was interviewed in January 2017 by director Jenni Matz for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of that conversation.

Q: How did your first TV writing credit, on The White Shadow, come about?

A: I was playing softball with some guys from New York and a friend said to me, “You know, one of the guys we’re playing with, Marc Rubin, works on this show called The White Shadow.” I had a bunch of ideas, so I called Marc’s office to see if I could pitch them.

Back in the day, when I wanted to pitch, they had me go on the lot. I was taken to a room with a square television set, and there was another guy there — he was there to watch the pilot with me. It turned out to be John Falsey. We hit it off, and the next day he called me. He goes, “Guess what? They bought my idea.” I was very happy for him but unhappy for myself.

That Christmas, I’m on the red-eye flight to New York and I hear somebody saying, “I just sold my second script to The White Shadow.” I look around, and there’s John Falsey. When I got back to California, I got a call from him, saying, “Why don’t you come in and pitch? Something opened up.” So I pitched to Marc Rubin and he bought one or two of my ideas, but that was it. I didn’t get to go to teleplay on any of them. I was devastated.

Months later I got a call out of the blue: “Hi, it’s John Falsey, and I’m the story editor of the show. I have to write an episode, and it’s got to be done in three days. Would you write it with me?” I said, “Absolutely.”

I didn’t know this guy. I’d met him on a plane, watched the pilot with him, but he seemed like a nice guy. So I did it, and then they gave me another one. I wound up writing six episodes for them, and then I got to be a story editor on The White Shadow. So Falsey and I were both story editors. We weren’t partners.

Q: How did you become partners, on St. Elsewhere?

A: Grant Tinker, who ran MTM, asked me what I wanted to do next. To backtrack, one of my college roommates — my best friend when I grew up — was Lance Luria. He did his residency at the Cleveland Clinic, one of the top hospitals in the United States.

He said, “Somebody ought to do a show about what goes on in a teaching hospital. It’s unbelievable.” So when Grant said, “What do you want to write next?” I said, “I’d like to do a show about a teaching hospital.” And he goes, “Hill Street [Blues] in a hospital.” Now, Hill Street was not on the air yet. I said, “Sure,” though I didn’t know what Hill Street was.

Then Bruce [Paltrow, an executive producer of The White Shadow and St. Elsewhere] called me from New York and said, “Well, what do you want, Josh?” I didn’t know enough to know what I wanted, but I said, “I want to create the show.” He said, “Fine, create the show.” I said, “And I want to be a producer,” and he said, “Fine, you’re a producer.”

So I asked Falsey, “Hey, John, do you want to work on this show?” and he said, “No, thanks.” I said, “But they want 13 episodes. We’ll be partners?” He said, “Yes.”

God bless my friend Lance. Doctors and cops don’t like to talk to people who are outside the fraternity. They don’t trust them. But they trusted Lance. We spent three days [at Cleveland Clinic], and we came back with all this great material. Lance would say to a colleague, “Tell me how you killed that guy last night.” I remember the answer, and I used it in the pilot. It was: “He was hemodynamically compromised.”

I don’t remember where exactly this was in the process, but we saw the Paddy Chayefsky movie Hospital — a very dark comedy about a New York hospital — and I thought, “This is what the show should be.” So we write this thing, but it turns out that it’s not a pickup for 13 episodes — it was really just the pilot script. We had to write 10 scripts before they picked up the show.

Q: Why did you leave the series after the first season?

A: I didn’t play well with others on that show. And it wasn’t their fault. I wasn’t happy. I was young, and I’d only worked on The White Shadow. I felt like this was mine. I had to learn something, so I left after a year. I was invited to leave. Falsey didn’t have to leave. He played better with others. But he wanted to leave. So then we were on our own.

Q: How did you start working on Amazing Stories?

A: One day I was reading in the trades — there was a little thing that said, “Steven Spielberg has a show of 44 episodes that has gotten picked up.” I called one of the executives at Universal and the next thing I know he says, “Well, Steven would like to meet you.”

We went over to his place on the Universal lot, and he was a lovely guy. I remember he said, “So, are you guys fans of The Twilight Zone?” I said, “I like it, but I’m not a fan.” He said, “Do you like science fiction?” I said, “Not particularly.” We had a nice conversation and I thought, “That’s the end of that.”

But I got a call that Sidney Sheinberg, the head of Universal, wanted to meet — they wanted us to do this job. So we worked on Amazing Stories.

It was an extraordinary experience that went beyond making a show: I got to work with Martin Scorsese and Clint Eastwood and the best composers, and Sam Waterston did one. It was an anthology; John would produce one episode, and I’d produce the other. And Steven Spielberg knew more about television than anybody I’d ever met. But once again, I was invited to leave at the end of the first year.

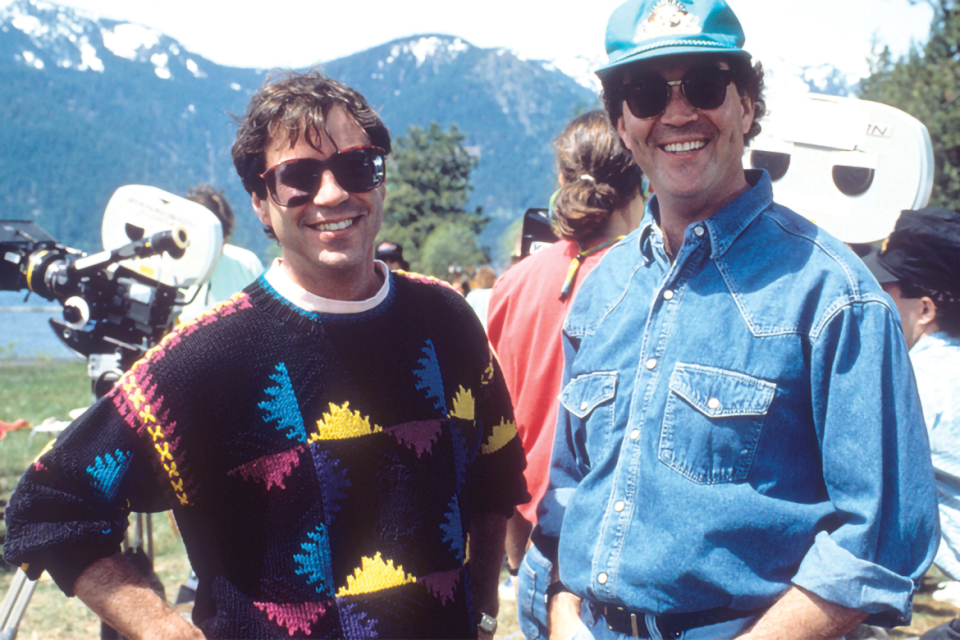

Q: Where did the idea for Northern Exposure come from?

A: A couple of things went into creating it. I was a big fan of the movie Local Hero. And I had seen a movie called Never Cry Wolf, which Carroll Ballard directed — these are both fish-out-of-water stories. In Local Hero, Peter Riegert plays a guy working for Burt Lancaster, an oil man, and he has to go buy out a village in Scotland so they can drill oil there. All the Scots are these wacky characters. There’s nothing like it.

I didn’t want to do another doctor show. But I knew that if you say, “a doctor in Alaska” — why Alaska? We knew we couldn’t shoot in Alaska, but we said, “It’s got to feel like it’s Alaska. It’s a new frontier. It’s where everybody goes to re-create themselves. Everything loose that isn’t tied down winds up there. It would be a fun place to do it.”

We had to figure out where we could shoot it. We went to Colorado, Seattle — we couldn’t find a place. I remember the location manager said, “I’ve got one more place to show you,” and took us to Roslyn, sixty miles from Seattle, over the Cascade Mountains.

In the town, there’s one main street and there was that mural of the camel painted on the wall that said, “Roslyn.” I remember I turned to him and said, “Well, the town was founded by…,” and we knew that we were going to call the place Cicely. I said, “Cicely and Roslyn, they were two lesbians and they basically founded this town.” And that’s how the town came about.

Q: What were the challenges of shooting Northern Exposure?

A: Everybody told me not to do it. My agents told me not to do it. My lawyer had told me not to do it. He said, “First of all, you’re not getting any money to make it. Second, nobody’s going to see it.” Nobody did summer replacement shows.

We had to go up to Seattle to shoot, but we didn’t have money for a real crew. I was directing, and they didn’t want me to direct it — I think they were afraid of my having too much power. But I said, “I’m not doing it if I don’t direct it.” They said, “We’re only going to pay you the minimum for an episode.” I said, “I don’t care.” I wanted to do it.

Q: Why so badly?

A: It was proprietary for me. I loved St. Elsewhere because I love learning. I’m a reader, and I love learning about things like Munchausen’s disease and coming up with crazy things. But Northern Exposure was closest to who I am.

I’m interested in ideas. I read about them. I like to talk about them. I like to think about them. And I’m interested in seeing things that are different. We were going to make something that would look different than anything on television.

I’m interested in challenges, [like] “How are you going to shoot it at a distant location?” I had a family, two kids. I wasn’t going to live there. I loved the script, so I wanted to do it. I also figured out by that time in my life — I was 30-something — anytime somebody is going to give you money to do something you want to do, say, “Yes.”

Q: And the show found an audience….

A: Yeah, we did eight episodes, then all of a sudden it was popular. Somehow people had found this summer show. It was a critical hit — the only show I did that was a critical hit. It was a top-20 show, sometimes a top-10 show, and it was a commercial hit. Everybody loved it.

I did 66 episodes, but at some point I was going to get fired from that show, too. I did something they didn’t want me to do. It was an episode [“War and Peace”] where Maurice and a Russian guy, Nikolai, had a duel. The characters go, “Well, they obviously can’t kill him.” Then they just walk off.

It was a version of breaking the fourth wall, and they didn’t want me to air that. They said they would lose the audience. I said, “I don’t care. It’s funny, it’s terrific.”

They aired it, but at the end of that year they flew me to New York and basically said, “Are you going to be a good boy?” I said, “I’ll be a good boy.” I kissed the ring. I went back to L.A. and thought about it. I went to Falsey and said, “I can’t do this. I’m sorry.”

I wasn’t negotiating. I wasn’t being a wise guy. I just didn’t want to do it. I left after five years. I felt like I was repeating myself and I just didn’t want to do that. I said, “I’ve gotten to do everything I want.” And while we were doing that, we also sold I’ll Fly Away and Going to Extremes.

Q: Tell us about those.

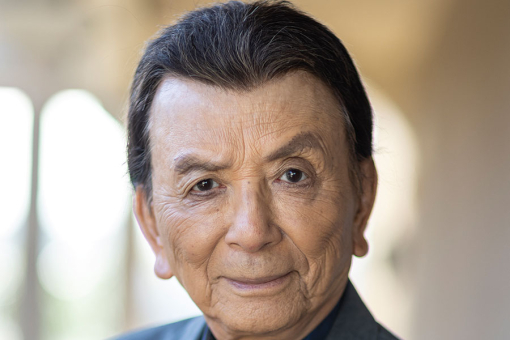

A: I’ll Fly Away was our idea for To Kill a Mockingbird from the black point of view. We set it in “universal time.” It was the opposite of Mad Men or The Americans — we didn’t want it to be period-specific. There was nothing other than cars that determined the period.

We walked out of the pitch and NBC said, “We’ll buy both of them.” So we’re in the parking lot and Les Moonves [now chairman of CBS Corporation, he was with Warner Bros. at the time], one of the greatest salesmen in the history of Hollywood, said, “So what do you guys want to do?

We said, “I don’t know…. We could do this one, we could do the other one.” And he said, “Are you crazy? They’re going to pay you money to do To Kill a Mockingbird as a network television show! You’ve got to do that one.” We went, “Oh, right,” and we decided to do that. So we sold Going to Extremes to ABC, which was an idea that Universal had.

I did not want to do another medical show [Going to Extremes was about med students on a tropical island], but we were getting to shoot it in Jamaica. It was like Lord Jim, the logistics of it. Jamaica had never shot a television show — you have to bring everything in.

And what we pitched was, “Jamaica doesn’t have a film school. So let’s say every third person on every part of the crew is going to be Jamaican. In the second year, they’re going to be the number-two person and we’ll get a Jamaican for number three. We’re going to be your film school.”

They got really excited about that. And I got excited — it was enormously satisfying. We had three television shows, and John Falsey and I did not believe in redundancy. We were into division of labor. Mine was Northern Exposure. John loved I’ll Fly Away. He loved, loved, loved it.

But we made a big mistake. We hired David Chase, and John said, “Here’s the deal: you can run either I’ll Fly Away or Going to Extremes,” which was brand new, thinking he was going to pick Going to Extremes because it could be his thing. David chose I’ll Fly Away, so John was stuck with Going to Extremes, which he didn’t love.

Q: What do you love about writing?

A: I never did love it — I used to hate it. When I was in the writers’ room and everybody else was having fun, I wanted to get out. But I found I could do it and I was good at it. And I started to love being in the room — by myself.

But when I was younger, I didn’t like it. I felt like I was being deprived of something. So I bridled against it, but now I love the submersion into a world — it’s like diving into clear water. There isn’t a place that I’d rather be.

I found out that there’s nothing in my life that I like more than taking an idea and seeing if you can turn it into something. Shaping something from an abstraction into something concrete. And that’s actually part of being a consultant [on The Americans]. Part of that was learning how to play well with others.

I would like to be a part of you doing the thing that you want to do, participating in a project that you think has value.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 7, 2017

For the full interview, click here.