Saturday Night Live … or Hollywood Squares?

That was the unexpected job choice Alan Zweibel faced in 1975 when he was working in a New York deli and trying to make it as a joke writer. SNL was yet to debut — Zweibel didn't really know what it was — and Hollywood Squares was an established success. But the SNL job sounded like more fun, so he took it, and the rest, as they say, is history.

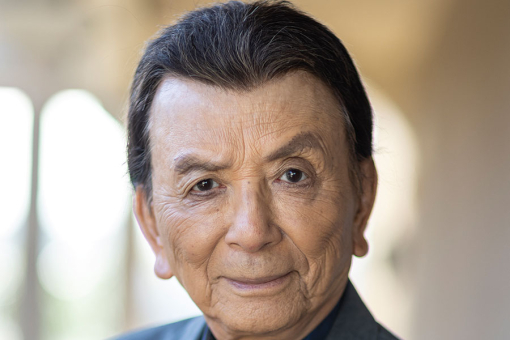

Zweibel ultimately stayed with SNL for five years. During that time, he partnered with Gilda Radner to create some of her most memorable roles on the show, and the two remained close until her death in 1989. Zweibel also cocreated and produced It's Garry Shandling's Show and worked with Larry David on Curb Your Enthusiasm.

Across his career, Zweibel has been nominated for eight Emmys and won three, in 1976 and 1977 for SNL and in 1978 for his writing on NBC's Paul Simon Special. He also won a Thurber Prize for American Humor in 2006 and was awarded an honorary PhD from the State University of New York in 2009.

In keeping with his friendship with Radner, he contributed home movies and photos to the 2018 documentary about her, Love, Gilda, and was an executive producer as well.

In addition to his work for television, Zweibel has written novels (one was a collaboration with Dave Barry), a children's book, screenplays and humor pieces for The New Yorker and Esquire. He also worked with Billy Crystal on the Tony Award-winning play 700 Sundays and its subsequent HBO special.

Married since 1979, Zweibel says the production he's most proud of is his family with wife Robin, consisting of three children and five grandchildren.

Zweibel was interviewed in November 2017 by Dan Pasternack for a coproduction between the Writers Guild Foundation and The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire interview can be seen at TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

Q: When did you start to get some traction writing jokes?

A: The traction is all due to my mother. My mom and dad went to Lake Tahoe and saw Engelbert Humperdinck. The opening act was a Borscht Belt comedian named Morty Gunty. My mom ran into him the next day and said that her son wanted to become a writer. He gave her his address and said, "Have him write me some jokes and mail them to me," and I did.

He liked them and he bought a couple. So I wrote for the Borscht Belt guys, but I grew bored after a couple of years.

Somebody told me about the Improvisation, a showcase club here in New York, and another one called Catch a Rising Star.

That's where Richard Lewis and Larry David and Freddie Prinze and Robert Klein and Lily Tomlin and Bette Midler would come. So I took all these jokes, and the plan was to go onstage and deliver them, as a writer. Just so people could hear my material. I had every hope that a manager or an agent hanging out at these places would like the material and help me get a job writing television.

Q: How did you happen to put yourself in front of SNL's Lorne Michaels?

A: I didn't know I'd put myself in front of him. He had seen me bomb at Catch a Rising Star. Lorne introduced himself — I didn't know who he was — he said he liked my material and he wanted to know if I wrote it and asked to see more. He was combing the clubs for writers and actors for this new show. So I showed Lorne about a thousand jokes that I had written.

Then I got a phone call, I think on my 25th birthday in 1975, that I'd gotten a job on that new show. On the same day, I was offered a job writing questions and bluff answers for Paul Lynde on The Hollywood Squares. I'm working at a deli, and all of a sudden I get these two offers!

Hollywood Squares was a network primetime show going into its ninth season on the West Coast, where the industry was on a higher pay scale. What a great entrée into the business, as opposed to this Saturday Night Live thing! Who the hell is up watching TV that late? Who the hell is John Belushi? And on the East Coast, you made like a dollar an hour.

I gave it all of 15 seconds of thought. But my mom said, "Well, which one will you have more fun doing?" I said, "This Saturday Night Live thing."

Q: What was it like, coming onto the scene at SNL?

A: My background was joke writing. Theirs was improv. I was blown away by their facility and ability to create something on their feet.

Q: How did you integrate yourself?

A: One strength I had was joke writing, and since there was "Weekend Update," I gravitated toward [writer] Herb Sargent, who was like the elder statesman. We were all in our 20s, but Herb was 54. He was a beautiful person, so it became like a father and son relationship. I found protection there. And the other place was just as effective, if not more so — Gilda [Radner].

Q: How did you initially connect?

A: I was in Lorne's office because we were supposed to tell our ideas for stories. But I had seen all these other people, and I was spooked by their talent. I was too nervous to talk, so I hid behind a potted plant in the corner. Then I heard a girl's voice from the other side say, "Can you help me be a parakeet?"

I parted the leaves and looked out, and it was Gilda. She said, "I think it would be really funny if I stood on a perch and scrunched up my face and spoke like a parakeet. But I need a writer to tell me what the parakeet should say. Are you a good parakeet writer?"

I had no idea what she was talking about. But at least somebody was talking to me. So I said, "I'm a great parakeet writer." She asked why I was behind the potted plant, asked if I was nervous and I said, "Yeah." She asked me if there was any room back there for her because she was nervous, too. So she came back, and that's where we met. Squatting behind the plant.

Q: It's almost a cinematic rom-com kind of "meet-cute."

A: The whole relationship was like that. In her own weird, crazy way — if you had enough tolerance for it — it was incredibly romantic. But it came with a huge amount of acceptance that she had some demons.

If she designated you as somebody that she depended on, that was your role. To a great extent back then, I was a brother. Lorne might have been her dad. She had to know where her stability was. We were platonic lovers, she and I. It's the only way I can describe it.

Q: In the fifth year of SNL, did you have a sense it would be your final season?

A: We had heard in previous years that Lorne wouldn't be coming back the next year. There were rumors. The last image of the last show of the fifth season — Buck Henry had hosted — was of the sign outside Studio 8H that says "On Air," and the light was going off. A day or two later Bernie [Brillstein, my manager] called and said, "Lorne's not coming back."

Q: Was there an understanding that if Lorne was leaving, everybody was going with him?

A: You had to be invited to come back. Jean Doumanian, who replaced Lorne, wanted me to be on her staff and I didn't want to. I thought, how much bigger and better and more successful could it be? I was exhausted. And opportunities were presenting themselves for movie scripts and TV shows and I just felt it was time.

Q: So you went to It's Garry Shandling's Show.

A: Bernie asked if I'd ever heard of Garry Shandling. I had seen him on Letterman and thought he was really funny. He was doing a special for Showtime. It was a really funny idea — The Garry Shandling Show: 25th Anniversary Special — they made believe it was the 25-year anniversary of his talk show.

I read the script and thought I could help. So I went out to L.A. and worked on it. Garry and I hit it off the first night we met. I called my wife and said, "I think I found a writing partner." It was like lightning had struck a second time. It was like it was with Gilda.

Garry and I were on the same page, but we had different strengths. Garry was better at structure and story. He had written for Welcome Back, Kotter and Sanford and Son and mainstream sitcoms. He knew the form and he knew what he was parodying. I was better at dialogue. The combination worked.

He had an idea for a show where he played himself talking to camera, about the life of a comedian. I had an idea for a show, independent of his, with a guy like me, a comedy writer who's married with kids. We combined the two into one show, with his character and a friend who's married with a kid.

Q: Did you initially conceive the meta-quality that came to characterize the show?

A: That evolved. When we came up with the title of the show, I said, "It's got to be different. Why don't we make it Garry Shandling's Show?" And he came up with the It's.

We wrote the theme song in an elevator at Bernie Brillstein's office. He said, "We're going to need a theme song." I said, "Should we start hiring people? What kind of theme song?"

He said: "Why don't we do a theme song about a theme song?"

I asked: "What does that mean?"

And he said: "This is the theme to Garry's show, this is the theme to Garry's show. Garry called me up and asked if I would write his theme song."

And I added: "I'm almost halfway finished. How do you like it so far? How do you like the theme to Garry's Show?"

Then he repeated: "This is the theme to Garry's show, the opening theme to Garry's show. This is music that you hear when you watch the credits."

And I said: "I'm almost to the part where I start to whistle, and then we'll watch It's Garry Shandling's Show."

We both started whistling and I think Shandling said: "This was the theme to Garry Shandling's Show."

By the time we got to the lobby we had a theme song. That's how I got along with Garry. It was truly magical.

Q: What led to Gilda's appearance on the show?

A: They thought she had Epstein-Barr virus. She ended up having ovarian cancer. I said, "How can I help?" She said, "Make me laugh."

At one point, when they believed she was in remission, Gilda and I took a walk on the beach and I said, "Do you want to come on the show? Are you ready?" She said, "Yeah, but I haven't been on TV in six, seven years. I'm afraid nobody's going to recognize me when I come through the door."

I was just starting to say, "Don't be silly…" when she said, "On the other hand, I've got to do your show. My humor is the only weapon I have against this fucker."

That's what she called the cancer. She personalized it and called it "fucker." Then she said, "Zweibel, can you help me make cancer funny?"

So that became our mission. We wrote a bunch of cancer jokes. She wrote most of them. The night of the show, she was unannounced. The audience just erupted.

Garry said: "Hey, Gilda. How have you been? I haven't seen you in a while."

And she said: "Well, I've got cancer. What's your excuse?"

He said: "Well, I've been stuck on this show, for which there's no cure whatsoever." When she said cancer, the whole audience — it was fascinating — there was a little gasp and then right on the heels of the gasp, it was as if the audience said, "Oh, she's allowed to do it because she has it."

Q: Right…

A: They gave in to the laughter. When I went to edit the show, on the shot that I wanted of her entrance, the frame was jumping just a little bit. I couldn't figure out why and then I remembered: the night that we shot it, the cameraman was crying.

She died on my birthday, which I think is incredibly ironic and so Gilda-like. It was as if, "Okay, asshole, you're going to remember." Whenever it's my birthday, we have a cake and a memorial candle next to it.

To this day I find myself writing for her, [asking] "What would Gilda do with this?"

My wife said: "You should write about you and Gilda."

I resisted and said: "I don't want to capitalize on that."

She said: "Fuck that. Your best friend died. You haven't cried yet."

It was true, and my way of dealing with it was, I wanted to recreate everything I could remember about the relationship. Four years after she died, I wrote a book called Bunny, Bunny. The whole book is dialogue. She talks, I talk, she talks, I talk… for 14 years, ending with my eulogy at her memorial.

I even illustrated it, and I can't draw. But I knew it would make Gilda laugh if she was around. That book was a way of keeping Gilda alive.

Q: What's the origin of Bunny, Bunny?

A: That was a superstition that Gilda had as a little girl. She felt that the first words she said when she woke up at the beginning of every month had to be "bunny, bunny," and that would make it a good month. Some people say, "rabbit, rabbit." She kept that superstition all through adulthood to the end of her life. The first of every month on Facebook I write, "bunny, bunny." That's my way of saying hi to Gilda.

Q: Let's return to It's Garry Shandling's Show … that was your first time as a showrunner.

A: I welcomed the role. I wanted to be the Lorne of my show. I got along with everybody in the cast and had their respect, but Garry was the star. He played a guy named Garry Shandling, which happened to be his name. At best I was vice-president. So there was a certain frustration.

Q: Why did the show end when it did?

A: It ended for me because I was getting bored. Garry wanted this to be a very personal show, but he was a single guy who lived alone and we were running out of stories. So for the last year of the show, I insisted that [his character] get married, so there could be more storylines. I think intellectually he thought it was the right idea, but he just didn't feel comfortable with it.

By this time I had three children. I was the commissioner of our son's Little League. There were other things happening that I wanted to write about. And he and I weren't talking, which I don't think led to the demise of the show, but it didn't make the prospect of coming back pleasant. We had just had it with each other.

Later, I was in New Jersey, and Robin read that Garry was appearing in Atlantic City. She got him on the phone and said, "Listen, I'm bringing Alan down. I'm putting the two of you in a room and you're not coming out until you're friends again. You've been through too much together."

And we had our talk. There was something about Garry that I loved, and I wanted to keep him in my life. I always had this pipe dream that we would find each other again creatively.

Ultimately I was out in L.A. and wanted to have dinner with him to discuss It's Garry Shandling's Show possibly being syndicated. He called me and said, "Do me a favor. Call me Thursday and we'll talk about everything." He died Thursday. He really went to an extreme to avoid talking to me.

Q: You weren't involved in Curb Your Enthusiasm from the outset…

A: In a way I was, but not officially. Billy Crystal, Larry David and I shared offices at Castle Rock. BiIly was writing a pilot with and for Jeff Garlin. I introduced Jeff to Larry upon Jeff's request. One day Jeff said, "I have an idea I want to discuss with Larry," and ultimately it became the Curb Your Enthusiasm special about Larry's return to stand-up, which became a pilot for Curb.

During the first year of Curb, Larry would come in and bounce ideas off me. In the second and third years, we made it official — I was a consulting producer. Then I appeared in an episode in the eighth season. I play a guy named Duckstein who wants to have lunch with Larry, but he doesn't want to have lunch with me. I basically chase him around the whole episode, begging him to have lunch.

Q: How is the real Larry David different from the character?

A: Larry David is an incredibly generous guy. He's a good friend. Does he have the naughty thoughts that the character does? Of course. The difference is that the character acts on them, whereas Larry and I will kid around and go, "What if…?"

Larry is — here's a word that's not used very often about him — he's incredibly sensitive. Because in order to be insensitive, you have to be sensitive to know what people are thinking and how they're feeling. That's where your comedy comes from.

Q: What do you like about writing?

A: I love words. I love word origins. One of the things that Herb Sargent and I bonded over were words. How certain expressions came about and the order that you can put words in to convey humor or sadness or whatever mood you want.

One of my heroes, who I ultimately spent time with, was Larry Gelbart. What Larry Gelbart had was something I think every writer should aspire to. Buck Henry is that way, too — there's an inherent wit. I don't claim to have their level of wit, but I love the process of taking words and trying to put them in an order where you make a person laugh.

There's also an omnipotence that a writer has, because you create a world, populate it with characters and they say what you want them to. The greatest part is that when you're successful, those characters tell you what they want to do and say. Even if you had preconceived that a character would do something, by that page you realize, "No, he wouldn't do that. He's telling me he wants to do this ."

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 7, 2019