On her way up the ladder as a dancer and choreographer in Hollywood, Anita Mann took every job she could — morning, noon and night.

As a result, she got to dance with Elvis, stand backstage with Mick Jagger while watching James Brown, and learn the studio business from Lucille Ball. The Detroit native even got to play Miss Piggy’s tap-dancing feet in The Great Muppet Caper.

It wasn’t always easy, though.

Mann’s ambitions to be part of the creative team behind the camera came at a time when women’s voices weren’t always welcome.

She explains: “A lot of male directors didn’t want to work with me or wouldn’t take my notes. The cameramen were always my friends. They’d say, ‘You should hear what he’s calling you,’ and I’d say, ‘Yeah, let me hear.’ But if it doesn’t kill you, it makes you stronger. And I just said, ‘Nobody’s going to stop me.’”

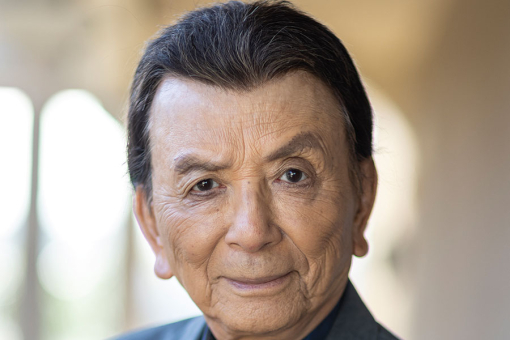

Nominated for five Emmys, Mann won one for outstanding choreography for the 1996 Miss America Pageant. With the iconic ’80s show Solid Gold, which she joined in its second season, she made her mark on popular culture. And in a career marked by working with greats, the greatest, she says, was Michael Jackson.

Mann was interviewed in April 2018 by Nancy Harrington for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire discussion can be screened at TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

Q: You appeared in your first film, Bye Bye Birdie, while you were still in high school. How did that come about?

A: The audition was announced in the newspaper. We didn’t have agents for dancers in those days. But I went to the audition and I got it. They had maybe a hundred dancers in a scene around a big fountain in a courtyard. That was the only number we were allowed to be in, because you had to be 18 to do other parts of the movie.

I watched Ann-Margret and Dick Van Dyke and it was just like heaven, every day. I went to school on the set. I did my homework and my parents totally supported my dream. I was really blessed that they would allow my dream to become my life.

Q: Then in 1964 you became a dancer for The T.A.M.I. Show.

A: Before The T.A.M.I. Show [a concert film featuring U.S. and English bands], I did about six weeks of Shindig! and then [choreographer] David Winters left for New York to do Hullabaloo. But in the interim, he did The T.A.M.I. Show and he asked me, Toni Basil, Teri Garr, Pam Freeman Parker and a bunch of other dancers to be on it, which was unbelievable.

Q: What was it like working with them?

A: Toni and I became very close — she was David’s assistant and I would help out behind the scenes or with some dancing. The T.A.M.I. Show was an incredible experience. Steve Binder was the director. It was two concerts shot in segments at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, and then he edited it together.

It ran in movie theaters as a closed-circuit TV special. It was one of the classic rock ’n’ roll shows of all time. Everybody was in it — Marvin Gaye, the Supremes, the Beach Boys….

Q: James Brown…

A: Well, James Brown was supposed to close the show, I think. But they booked the Rolling Stones to close instead — they had come over from London, and I don’t think James Brown was thrilled about that decision. While he was performing, Pam and I were on stage right with Mick Jagger, waiting for the finale, and he was watching James Brown.

James did not want to get off the stage — they were dragging him — he was doing the cape thing and the dramatic exit, a phenomenal performance. Mick Jagger said to us, “How the… something … am I going to follow that?”

He went out onstage, and if you watch some of the guys in his band looking at him, it was the first time he was doing all those jumps and movements. He got so motivated by James Brown’s performance that Mick Jagger actually started his thing that night.

Q: In 1966 you appeared on a few episodes of the Ozzie and Harriet show.

A: Oh, yes. Kris Nelson was married to Ricky Nelson — she was a dancer on Shivaree and we all became friends. I loved working with the Nelsons. They were a family of talented people, and it was my parents’ favorite show. That was pretty special.

Q: Were you hoping to do a little acting at that point? Or did you just want to dance?

A: I didn’t like going to makeup, getting my hair done, having to be in front of the camera. I always loved being behind the camera. I loved creating and I loved dancing. I memorized lines and I did a lot of commercials, which I did to support my family. I did like doing commercials. And I did get a lot of acting parts, on Mission: Impossible and Love, American Style.

I had a wonderful acting teacher, Leonard Nimoy, who sadly we’ve lost. But I learned from him how to break down a scene and a character and how to make it real. But I did not want to be an actress. I wanted to dance, create dance and be a creative part of the industry. I wasn’t as good at acting — even though I could get the jobs, I was more special in the dance world.

Q: What about Elvis Presley? How did you start working with him?

A: In the days of the Screen Extras Guild, you’d register as a dancer and you’d call in at 4:30 or 5 to see if you could work the next day. We didn’t have cell phones. You’d wait in a line to get to the phone when you were on a break. I was always the first person in line. I was always so proactive to get work.

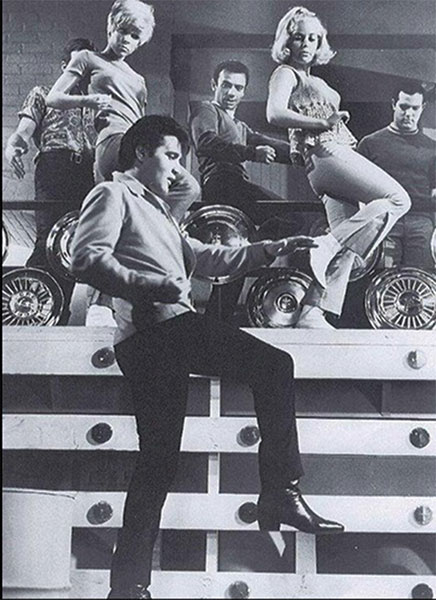

I got an Elvis movie [Spinout], and a lot of my friends were on it. It was a good party scene of dancing. So I’m onstage, I think it was at MGM, dancing and watching the cameras moving, and I was watching Elvis — he was always doing the same walk on the same words. And they were moving cameras and doing what I learned later to be reverse shots, close-ups, different angles.

Now, you’re not allowed to be choreographed when you’re an extra. You just danced. So I decided to make up my own routine — four ponies, four turns, four wild moves, four Watusis — and I did the same routine each time. The next day, the choreographer came up to me and said, “Mr. Presley would like to talk to you.” I thought, “I’m getting fired because I made up a routine.”

They said something to me like, “We’ve been watching you dance.” They said the editor was cutting around me, and I didn’t know what that meant. But my arm was always in the same position on the same lyric — it was matching. Jack Baker was the choreographer. He said his assistant couldn’t assist him on the next Elvis film [Clambake], and would I be interested in assisting?

I was 18 or 19. I said, “I honestly don’t know what that means, but yes, I would love to.” But I really was petrified. I immediately went to the library and checked out books about camera work, photography and lighting and tried to learn as much as I could before I started.

When there was a little ad lib part [on Spinout], I was supposed to go as fast as I could and shake, and then Elvis kissed me, as part of the film, and I thought, “I’m getting paid for this?” It was impossible. Then Jack Baker took me under his wing and I became his assistant, and he was Lucille Ball’s choreographer.

Q: You worked on The Lucy Show and also Here’s Lucy. What did you learn from Lucille Ball?

A: Lucy owned the studio that we were working at, and she let me use all the facilities. I went to Glen Glenn Sound. I learned how to edit. I learned to direct. I watched every camera movement.

She taught me how to run a studio if I ever needed to. She taught me how to produce, and I eventually became a producer.

She taught me how to be disciplined. What she showed us was her never-ending work ethic.

She wasn’t late, ever. She would have her lines memorized. She was ready to rehearse. She was dressed and ready to go.

And that work ethic is what gives you longevity. You have to have the talent to back it up, which she certainly had. But the hard work and understanding where everything is on the set — that’s a team effort. If you want everything to look the way you want it to, you’d better know what the team is doing and be a team captain.

She taught me not to be afraid, not to fear what other people might think of you. As a woman, she was one of the most influential, for me, in entertainment, because she owned the studio. She ran the lot. It was her name in the title, The Lucy Show and Here’s Lucy. She gave me inspiration.

Q: In 1975, you began choreographing for the second season of Cher’s variety show.

A: Dee Dee Wood was the choreographer the year before — she’s just brilliant. I admire her work so much. She had to move, and I had worked a lot with the director and the producer and I knew Cher from Shindig! So I was asked to come in for the season. I didn’t have to audition because they knew my work. I did that whole season and we had the best time.

Q: Talk about working with Cher.

A: Cher is really a natural, though she’s not a dancer. Sometimes I’d think she wouldn’t have enough time to rehearse because she did skits and so many other things and had to have her music and her Bob Mackie fittings — she was doing so much.

But she could watch a routine a few times and get up and do it. I remember we were doing a number called “Witchy Woman,” and I’d lowered her in from the ceiling — she was up for doing fun things.

Her costumes were very important, so I had to find out what she was going to wear. I would always sneak in to see what Bob Mackie had designed for her. Sometimes she’d have a feather on her back, so you couldn’t do certain movements. Sometimes one leg would be bare, or one arm. Fashion was very much a part of her incredible look.

But she worked so hard. I was in heaven with her. She could pull anything off. Sing it live. Dance it. She knew every camera. That show was really choreographed for cameras. I’d have her turn, that was her close-up, boys were going to circle her, she would look over there, she knew when the overhead shot was. We didn’t have much camera blocking time.

Cher was phenomenal.

Q: Let’s move on to The Jacksons series. How did that come about?

A: Michael was in a class — in outer space — by himself. When we heard the Jacksons were doing a summer series, everybody wanted to do it. I had worked with that team on another series and they said, “Do you want to choreograph The Jacksons?” Elvis, Cher, Lucy and now Michael Jackson?

There was nothing Michael Jackson could not do. Nothing. Michael was a dream to choreograph. There’s nobody like him. I never choreographed Baryshnikov — I think I once did something for Rudolf Nureyev — but for pure talent, he was the number-one person I’ve ever choreographed. I can say that clearly.

Q: You also worked with Jim Henson and the Muppets….

A: I met Jim in 1975 on Cher. I had just had a baby, so I was watching Sesame Street — I’d be cooking and the baby was in a highchair and I had Sesame Street on television. When Jim came to CBS, I would hear people saying, “Wait, what are these puppets doing?” And I would say, “You guys don’t know who’s in our studio? Kermit the Frog, Miss Piggy…?” I knew everything they did.

When the Muppets appeared on The Cher Show, there was a big character called Sweetums. I knew his backstory so I said, “Let’s have Cher sing [the Beatles song] ‘Something.’ ” Sweetums is going to be in love with her. He’s going to walk from the back and bump into everything and knock over pillars and trees, she’ll be singing and not knowing. We had fun working together.

Q: What are the challenges of working with the Muppets?

A: Well, they’re not real. Did you know that? They’re not real.

Q: Really?

A: They’re little creatures. And you end up talking to them. You could be standing right next to [puppeteer] Frank Oz and he’s got Miss Piggy and you go, “Okay, Miss Piggy….” They become people.

The challenge is, they don’t have feet. And you’ve got to choreograph them in a rolling chair. You have to choreograph the chair and keep it shot in a way that you don’t see it. But how do you see the dancer? So you learn how to shoot it, stop, change it out. It’s not an easy task.

Q: We see Miss Piggy’s feet in The Great Muppet Caper.

A: My feet.

Q: Were they?

A: They were my feet. The tap routine, when they pan down… that was me. I can tell that. Can’t I? Because she didn’t really have feet. Do people know that?

Q: How did you become involved with Solid Gold?

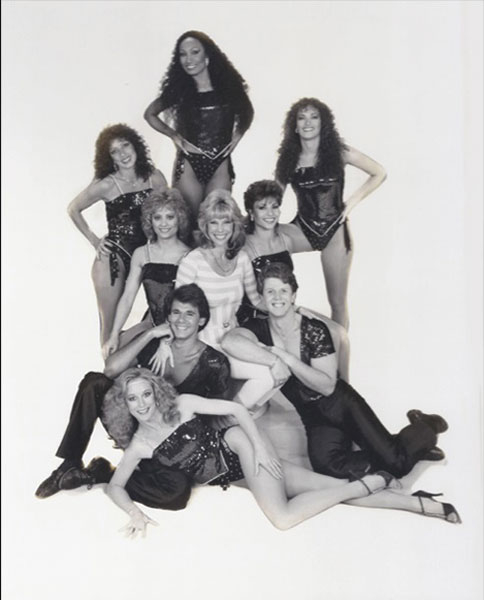

A: I had worked with the team on other jobs and they said, “There’s a pilot that we’re going to shoot; would you be interested in choreographing it?” And I said, “Oh, yes.” So we started talking about six women and two men and what the look was going to be.

But something came up in my personal life and I had to quit. It was a really tough experience, but sometimes you have to take care of family obligations.

But [choreographer] Kevin Carlisle and I had a very similar style. I was his assistant in 1972. He was perfect to do Solid Gold. He knew my style and I knew his — so he did the pilot and it was sold. That was in 1979.

Then things came around, and I started working again. A year and a half later, Kevin had to leave the show. They called and asked me if I would come in the middle of season two, and it was a seamless transition.

Q: What did you look for when hiring Solid Gold dancers?

A: The first thing I look for is attitude. If somebody has a bad attitude, that’s not going to fly. I watch every dancer walk into the room. I see who puts their dance bag down or shoves somebody else’s bag away. I watch when they’re learning the routine — who tries to get in front of somebody else.

The next thing is dancing skill and how quickly they learn the routine. A mistake on camera costs money.

Q: Did you ever experience any interference from the networks?

A: I did get letters that our costumes were too sexy, from some religious people on television, who said basically, “Burn in hell,” because I was exposing bodies in a certain way. I think bodies are beautiful — we’re not exploiting the bodies, we are just using our strengths.

I would get comments about partnering certain people — not on Solid Gold as much, but in the ’60s I was dancing in the Petula Clark special — she put her arm on Harry Belafonte and the show went off the air, right at that minute. At NBC. We couldn’t believe it. The T.A.M.I. Show was one of the first hugely integrated shows in 1964.

As a dancer, you don’t think about who you’re dancing with. It’s our art, our job.

Q: As a woman in the industry, have you faced discrimination?

A: Did I just laugh? Yeah. Of course, I did. First of all, in dance clothes, you look like an easy target. I would always cover up. Going into the meetings, I’d put on a dress. But I was the only woman in most of the pre-production, executive and network meetings in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s.

The movement now — to bring to the forefront what women dealt with or are still dealing with — I think it’s critical. But it was hard. Really, really hard. There was so much discrimination against me. I’ve been called names, and a lot of male directors didn’t want to work with me or wouldn’t take my notes.

The cameramen were always my friends. They’d say, “You should hear what he’s calling you,” and I’d say, “Yeah, let me hear.” But if it doesn’t kill you, it makes you stronger. And I just said, “Nobody’s going to stop me. I know what I can do — and I will.”

But I did it with integrity, and no one could get to my insides. I would get in my car sometimes, drive home and cry, “How could that man be so rude to me? How could he do this?” But I’d say, “It’s not going to get to me. It’s not going to stop me from accomplishing what I want to do.”

Q: What advice would you give an aspiring choreographer?

A: Follow your dream. Follow your passion. if you’re a great dancer and you know what you’re doing about movement, you can probably become a choreographer. But to become a great choreographer — as a living — you have to be willing to learn and collaborate and not think that your way is the only way.

Put yourself out there. People aren’t going to necessarily knock your door down.

But you do have to have other ways of making a living. If you can, teach. I think work breeds work. The more work you do, the more people you meet. And don’t worry about how much money you’re going to make. Don’t be a diva. That’s a lot of advice, but I want to help whomever I can. It’s not easy. But don’t give up.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 8, 2018