Before the comedy clubs, the television and movie sets, the Broadway stage and the awards, there was 549 East Park Avenue. The childhood home of Billy Crystal, on New York's Long Island, was where it all began.

The household, which included parents Jack and Helen and two older brothers, was a lively training ground for a budding entertainer. Jack Crystal was the manager of the famous Commodore Music Shop and, later, a concert promoter and producer who frequently invited musicians — including jazz greats like Arvell Shaw and Billie Holiday — to the house.

There, Billy, with brothers Joel and Rip, entertained family and friends with comedy routines by Bob Newhart, Rich Little and others that they heard on the records Jack brought home.

An actor, stand-up comedian, writer, producer and director, Crystal has worked nonstop in television and film since the 1970s. Though his planned performance was cut from the very first episode of Saturday Night Live in 1975, he found plenty of other jobs in television, including a role on Soap that marked a cultural milestone.

He played Jodie Dallas, one of the first gay characters on television, for the entire run of the ABC comedy, from 1977 to '81. In later SNL appearances, Crystal — as the smarmy talk-show host of "Fernando's Hideaway"— used his Fernando Lamas impression to popularize the catchphrase "You look mahvelous! " He went on to create iconic movie roles in When Harry Met Sally (1989) and City Slickers (1991).

No matter where Crystal takes the stage, he succeeds. He hosted the Academy Awards nine times to popular acclaim and helped raise funds to combat homelessness as a cohost of HBO's Comic Relief with friends Robin Williams and Whoopi Goldberg.

In 2004, Crystal debuted 700 Sundays, the one-man stage production in which he recalled growing up on Long Island and his relationship with his dad, who died when he was 15. He won a Tony Award for the show, which he subsequently adapted as a book; a film of the stage production was shot for HBO.

With six Emmys and a Mark Twain Prize in addition to his Tony, Crystal is hardly resting on his laurels; he remains busy as an actor, voice artist, writer, producer and director. His upcoming projects include the independent film Here Today, in which he is starring (with Tiffany Haddish) as well as producing and directing from a screenplay he cowrote with Alan Zweibel.

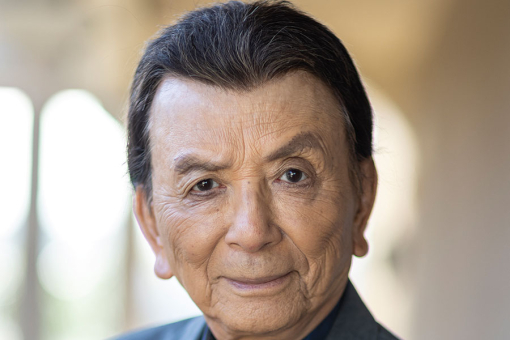

Crystal and his wife Janice have been married since 1970; they have two daughters and are grandparents. He was interviewed in October 2018 by Dan Pasternack for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire interview can be seen at TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

Q: How did you first get interested in comedy?

A: We always had a house full of funny characters. The relatives were hilarious. I started doing stand-up with my brothers; my mom had all the props. At school, I was always the class comedian — not the class clown. The class clown was the guy at graduation who hiked up his gown and had nothing on underneath. I was the class comedian, the guy who talked him into doing it.

Q: When did you start to pursue acting — in college?

A: I went to Nassau Community College and took Acting 101. I fell in love with it. I directed there for the first time. And I was making my own home movies on a Super 8.

I applied to NYU and got into the film program. There were only 30 or 40 students, but Oliver Stone was there, Chris Guest, Michael McKean…. And my professor of film production was Marty Scorsese. He was terrifying. He'd stand behind you at the Moviola going, "What did you do that for? Why don't you use a wide shot? Howard Hawks would have used a wide shot." I said, "Howard Hawks? I'm 18."

Q: And after college you started performing in a team?

A: A three-person team, with two of my great friends from Nassau Community College. We were called 3's Company and were together four years.

One time we were auditioning for Ed Sommerfeld, the manager of Sha Na Na. He says, "You guys are really funny. Buddy Morra just walked in, Robert Klein's manager. Can I bring him in to see you? And he's with Jack Rollins and Charlie Joffe. Do you mind?"

So we said, "Of course not." They're the top comedy managers in the city.

I got a call the next day from Buddy going, "Have you ever thought about being a stand-up? We think you could do it."

And around then I also got a call from my friend at NYU: "Do you know a comedian that could do 15 minutes for a party at ZBT fraternity house on Mercer Street?"

I'm feeding my daughter, and I went, "Yeah, I'll do it."

He goes, "When did you start doing stand-up?"

"Oh, been doing it for a while."

I'm lying my ass off as I'm wiping oatmeal off my daughter's face, because during that time, I was the house husband. I was taking care of Jenny while Janice was working. So, I go do this gig at the fraternity house, and Buddy and Jack Rollins came. I wound up doing over an hour of stand-up. Buddy and Jack looked at me and went, "The act stinks, but let's go to work."

Q: How did you hone your act?

A: Well, I'm at it for three months, and then Jack Rollins comes to see me again. I killed that night and we go out afterwards. I'm nervous because he's the guy who put Nichols and May together. He turned Woody Allen from a writer to a comedian to a director.

He says, "How do you think you did tonight? How'd you feel?"

I said, "I felt great. The audience was great. I thought all my timing was good. It was a strong show." Pause.

He sighs. "Okay. I didn't care for it." I could feel my hand reach for the knife at the table.

Q: For him or for you?

A: It was going to be Norman Bates. I said, "Why?" Trying to act cool.

He said, "Effective, yes. And that may serve you well. But it was all bits. You didn't leave a tip."

I go, "What do you mean?"

"A tip. The little extra something you leave on a table to tell the waitress you did a good job. They remember you because you left a tip. I know nothing about you. I want you to go home and tomorrow, when you come back, talk about your life. You're married, yes? You're a father? Talk about that. And be prepared to bomb. Don't work so safe. Leave a tip."

At first, I was enraged. I went home. I didn't sleep.

Next morning, I'm playing with Jenny. Mister Rogers' [Neighborhood] is on. And I'm thinking about my role as her father. I started making notes. I went back that night, talked about being the only man in the play group with the other women. I talked about Mister Rogers. And the next night it got better.

I put myself into it. I left a tip. Whenever I'm asked by young comics for advice, I tell them that story because I still think about it whenever I go on stage.

Q: How did your acting career take off?

A: I did a night at The Comedy Store, and Charlie Joffe filled the room with great television producers and executives. Norman Lear was there, Michael Eisner, Carl Reiner.... I did a 45-minute set and it went really well.

I go back to Long Island and a week later, the phone rings. It's a woman saying, "Would you hold for Norman Lear, please?"

"Really? Sure."

"Hi, kid. It's Norman Lear. Listen, we have a part on All in the Family coming up. I think it could be really good if you do it. We'll bring you out. You play Rob's best friend."

I said, "Of course." I was flown out to L.A. I played Al, the nut boy. We had a great time.

Q: Let's rewind the tape to talk about Saturday Night Live.

A: By late summer of '75, I'd been working a lot. This young producer from Canada named Lorne Michaels starts frequenting The Improv and Catch a Rising Star. He's looking for funny people for this show called NBC Saturday Night. He signs me to be on the very first show, October 11, 1975.

We do the run-through the night before. I did a non-traditional piece and it played great, but it was long. At the end of the night, Lorne was doing notes, cutting this, moving this. He said to me, "I need two minutes." I said, "Take two minutes out?" He goes, "No. I need two minutes total."

Q: How long was the piece?

A: About five-and-a-half, six minutes. I went, "Whoa." My managers come and talk to Lorne, who said, "Two minutes is all I have room for. The show is running long." I didn't have anything else. I didn't have a two-minute bit. So I got bumped from the very first SNL.

Q: How did you get involved with Soap?

A: I had a development deal with ABC out of that Comedy Store night that Michael Eisner was there for. We were trying to get something off the ground.

I get a call from Buddy Morra: "ABC wants you to read this script called Soap. It's a contemporary soap opera. The pilot is two half hours put together. There's something really special here, but you should know, the character is gay."

I said, "Is he funny?"

And he said, "Yeah. There's not much to do in the first half hour, but the second has a really funny scene. You should go meet the creators. They're great people."

It had a really funny writer, Susan Harris, who had written for All in the Family and Maude. And young producers, Tony Thomas and Paul Witt. And the director was Jay Sandrich, a giant of television directing.

So I go to meet them in late 1976. And they tell me about this character, Jodie Dallas: "He's a gay man. He is very honest about who he is. He's very positive. He's very funny. And we think that there's a long life for this character."

I knew that if we did this right, we could make a change in the way gay people were represented on television. It was a different America then. There'd never been a recurring, openly gay character in a primetime series. I so trusted the creative group that I said, "Okay. I'll do it."

Q: What was your experience making the pilot?

A: In the second half hour, I'm in my mother's clothes while she's out. I'm all dressed up in a wig and a dress, primping in front of the mirror. She comes in and she screams, "Jodie, stay out of my closet! What are you doing with my… Oh! You wear it belted. I never would have thought to wear a belt." I said, "Oh, yeah. If you do that, then everything just flows." It was very funny.

Q: How was Jodie received?

A: From the general audience, great. There were some gay groups that were upset that he was a stereotype. I felt that, and we made him more real. The proof of that was when he had a one-night stand with a woman, which ends up producing a baby. And there's a custody battle. ABC did a poll, and America wanted Jodie to have custody of the baby.

I thought that was a victory. That was big that they trusted a gay man with a child at that time.

Q: Were you still doing stand-up at that time?

A: Yeah, I did my first HBO special in '79, in the second year of Soap. Michael Fuchs, who created HBO, was the executive producer of that show. I loved doing that. It got really good reviews and people really liked it.

So, I wasn't just Jodie; I now had myself back. But as I look back on Soap, I'm really proud of what we did. I'm really proud that we hit some moments that had never been done before. As flawed as some of the moments were, I always look back on it and go, "We did something important there."

Q: Tell us about your 1982 variety show on NBC.

A: Brandon Tartikoff, the head of NBC, wonderful guy, comes to me with the thought of doing a summer variety show. We make a deal for six shows called The Billy Crystal Comedy Hour. We taped the first two and they were okay. But those shows take a while to develop.

Q: You did your Fernando Lamas impression there, right?

A: Yes, but Fernando really got going on my second HBO special, A Comic's Line, which caught Dick Ebersol's eye. He was now producing Saturday Night Live. Lorne had left. And I got a chance to host the show. I had the best time. Then I hosted again that year and it went very well.

That summer, Dick calls me and says, "If I could get Chris Guest, Marty Short and Harry Shearer, would you be a regular on the show?" I thought about it for two seconds and said yes. So we moved back to New York. And I think we energized the show in a different way.

Q: Why did you leave after that year?

A: I got a call from a director, Peter Hyams. He wanted me for a movie, Running Scared. We made the movie, but in the interim, Dick Ebersol left SNL and Lorne came back. He wanted to start from scratch with a new cast, so that was it.

Q: Let's talk about Comic Relief.

A: [Then–HBO chairman] Chris Albrecht and [comedian] Bob Zmuda came to us [in 1986] with a concept of a telethon on HBO, four hours, to raise money for the homeless. They wanted Robin, Whoopi and me to host. We all said yes.

And it couldn't have been more delightful, more creative and more impactful on our personal and performing lives. We raised a significant amount of money in the first one, and we were then brothers and a sister for all the rest of the specials. Comic Relief bonded us as family.

Q: You had a lot of projects at HBO — you did several more specials.

A: I think my favorite of the six HBO specials I've done is Midnight Train to Moscow.

Q: Whose idea was it for you to go to Moscow before the fall of the Soviet Union?

A: Michael Fuchs. Michael is a genius. He said, "Would you think about doing a show in Russia?" Gorbachev was in power. [It was 1989.] It was still the Soviet Union. But we make a scouting trip in April to St. Petersburg. And there's a midnight train from St. Petersburg to Moscow. So I went, "Well, I got a title."

And in Moscow, lo and behold, a cousin of mine is there telling me about all this family that we have there. That gets on my mind. I thought if I could come out and speak Russian for the first five minutes, that'll endear me to the audience. So we write a monologue in English, and I had it translated into Russian. And I learned it in Russian, phonetically.

I walk out and do the Russian jokes. And they killed. I don't know why, but I was not nervous. I had nothing to lose.

My cousin found 30 family members who we didn't know existed. That's what the show became about. I started out as a kid performing for my relatives and now I'm 12,000 miles away from that house, again performing for my relatives.

Midnight Train to Moscow won an Emmy.

The degree of difficulty on the show was tremendous. To take a show to Russia and score was something I am really proud of. And the lesson for creative people is, don't say no. Don't say you can't. We investigated. We researched. And we found a way in with honesty, with heart and with humor.

Q: Let's talk about the awards shows. You've hosted several Grammy and Oscar telecasts.

A: I had a great time doing the Grammys. Then movies had started to happen for me, and I got asked to host the Oscars. I've done nine of them now. Some of my favorite moments have been on that stage.

Q: Can you share some?

A: There's a moment that I think is my proudest moment as a stand-up. I'm supposed to introduce Hal Roach, one of the fathers of screen comedy. He was sitting in the second row and was supposed to stand up and wave.

I said, "Ladies and gentlemen, he's 100 years old, one of the giants of film comedy. I am so thrilled that he's here in person. Mr. Hal Roach." He stands up and waves. He gets a huge ovation. But then he starts talking. Without a microphone. And I'm 10 feet away.

I see a young man with a microphone trying to get it to him. I know the red light is on me. I've got jokes flying through my brain. Then one just sort of stuck. I went, "This is perfectly fitting. He got his start in silent films." And the audience went nuts. I walked off going, whoof. Fast ball on the outside corner.

Q: What is your proudest career achievement?

A: I'm lucky that I'm still here and still healthy. I'll leave you with this little story: I have almost a 50-year marriage, two great daughters, and the husbands they have are great. Four grandchildren. The little guy is very much like me. I see it. When he was three, he said, "I want to be like Grandpa. I want to be a chameleon." Because he couldn't pronounce comedian. That was the coolest thing.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, issue No. 10, 2019