It's hard to remember a time before reality TV.

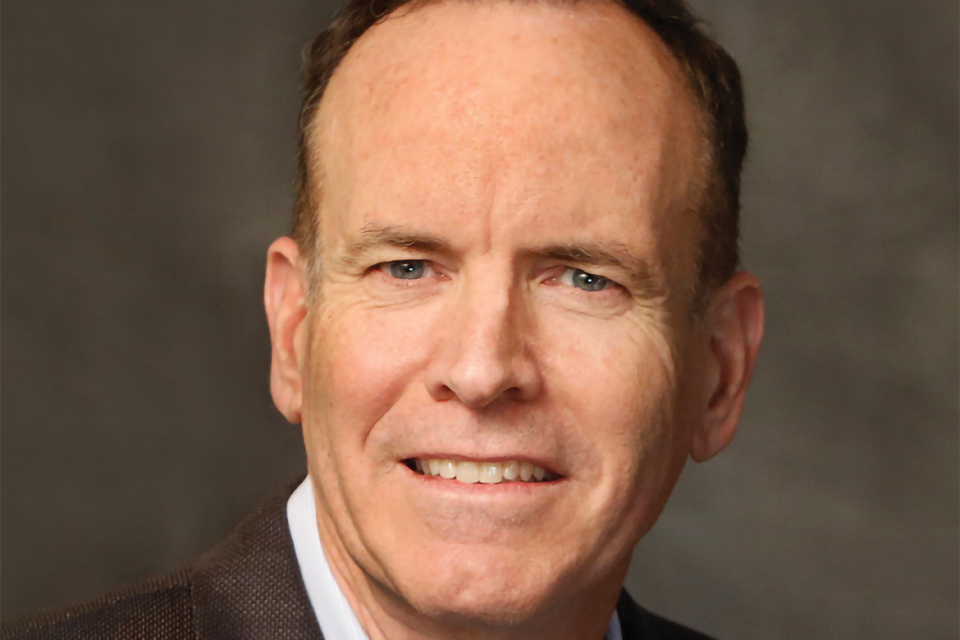

Jonathan Murray, half of the Bunim/Murray team that created MTV's The Real World, admits that he and his colleagues didn't necessarily realize that they were breaking new ground back in the early 1990s.

But The Real World, with its honest depictions of young people experiencing life's ups and downs, shifted the television landscape. And Murray, with a knack for reading human emotions and a desire to tell universal stories, helped demonstrate how watchable reality could be. "A lot of us were figuring this out and we were making a lot of mistakes," he says of the early years of the genre. "Luckily, we were learning from those mistakes. We all learned together."

A native of Gulfport, Mississippi, Murray split his formative years between the South and upstate New York. After graduating from the University of Missouri's prestigious journalism school, he embarked on a television career that presented some early obstacles but ultimately led to resounding success — and respect.

Murray has been nominated for 11 Emmy Awards, including seven as an executive producer of Lifetime's Project Runway and two as executive producer of A&E's Born This Way, the acclaimed reality series about a group of young adults with Down syndrome. He has won two Emmys, one for Born This Way and one for Autism: The Musical, a documentary seen on HBO in 2008.

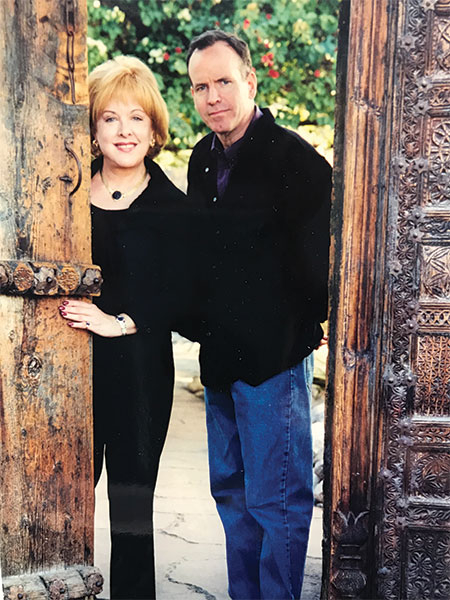

In 2012 he was inducted into the Television Academy Hall of Fame with his late production partner, Mary-Ellis Bunim.

Murray was interviewed in December 2011 by Stephen J. Abramson for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire discussion can be screened at TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

Q: What interested you growing up?

A: I had a huge interest in television, to the point where my parents used to try to ration the amount I would watch. I was probably 10 when the Syracuse [New York] affiliate put The Billy Graham Crusade on, preempting Gilligan's Island.

I marched down to my local hardware store and got an antenna to put on our roof so that I could get the Rochester station. I also would write to TV Guide regularly to get the ratings, because at that time newspapers didn't publish ratings. I was abnormally focused on television at a very young age.

Q: What were your favorite shows?

A: I watched everything from Bonanza to The Smothers Brothers. Then as PBS came along, I watched a lot of things with my parents, including in 1973 the landmark series An American Family, which had a deep impact on me. As I got older, I became more interested in the documentary form. I had a Super 8 camera and would shoot films and edit them.

Q: Where did you go to college?

A: I did two years at Geneseo State in New York, where I was a political science major. They didn't have the kind of television, film or journalism courses that I would need to pursue this interest in television, so I transferred to the University of Missouri and got a great education in journalism and broadcast news.

Q: What were your first jobs?

A: The University of Missouri School of Journalism owned an NBC affiliate station, so I was producing the 10 o'clock news at that station in the latter half of my senior year. With that tape, I was able to get a job just four days after leaving school. That was in Green Bay, Wisconsin, producing their 10 o'clock news. Then I proceeded from one market to the next, increasing my responsibility.

After a year or more of doing television news at WOKR in Rochester, I felt like I needed a bigger challenge. The program director was leaving, so I managed to talk myself into the programming job. After three years, I started to come up with my own TV ideas and pitched them back to the people who were pitching me their shows.

Q: Where did you meet Mary-Ellis Bunim?

A: I came up with an idea called Crime Diaries. My agent at William Morris, Mark Itkin, really liked it. He said, "You're great, Jon, but you've only worked in local television and in New York as a programming guy. You need to be with someone who's worked in Hollywood." Mark suggested Mary-Ellis, and we developed Crime Diaries over the phone and via fax.

Then I flew out to California and she picked me up at the airport — it was the first time I physically met her. We went off and pitched to various places. Mary-Ellis and I loved working together. Ultimately I stayed in California, and we started working on other ideas.

Q: What were your first impressions of her?

A: She was really experienced. She was one of the first high-powered females running soap operas. And she was a perfect partner for me. She knew how we could construct Crime Diaries at a low cost with modular sets, and with a production schedule that would allow us to make it for $50,000 an episode, which seems almost impossible today.

Q: How soon after Mark put you together did you decide to form a production company?

A: We did the Crime Diaries pilot, and while we were waiting to see whether it would sell, we started talking about whether we wanted to stay together and keep going at this. We both wanted to, so Bunim/Murray Productions came into being.

Q: What kinds of shows did you want to do?

A: At the beginning we focused on low-budget scripted shows and documentary-like shows. I don't think the word reality had been born yet. One of our first big breaks was selling an updated version of An American Family. We called it American Families; we were going to follow different families through a crisis or a transition.

Q: And that sold?

A: We ended up airing [only] the pilot, which was very frustrating. I had left a very successful career in New York. These were frugal times, and we were anxious about not getting shows on the air and not knowing where the money was going to come from. Then Mark Itkin called us and said MTV was interested in doing some kind of a scripted soap opera.

Q: That sounds like the birth of The Real World. How did it come about?

A: The idea was to do a soap opera about young people starting out their lives in New York. Mary-Ellis worked with a writer, and they developed a script called St. Mark's Place. It focused on a group of young people living in the East Village.

Everybody was really happy with the script, and we did the budgets for what it would cost to make. But suddenly there was this feeling [at MTV] of, "We can't spend this kind of money — we have a channel where basically we air music videos for free." So it all fell apart.

Mary-Ellis and I started talking about, "Well, maybe there's another way of doing this." We were doing American Families at that time, which could definitely be used as an example of what we could do.

We went to New York and met Lauren Corrao, the development executive under Doug Herzog [at Viacom, parent company to MTV]. We pitched her the idea of The Real World. We said that rather than a scripted show, we wanted to make an unscripted show. We talked about casting six young people of different races and socio-economic backgrounds, putting them together in a loft and following them as they take that big step in their life when they're in the real world on their own.

MTV ordered a pilot, and on Memorial Day weekend in 1991 we moved six young people into a loft on Broadway near Spring Street and shot for the long weekend. Then we spent about four months editing together two half-hour episodes. It was a really exciting way of telling a story that wasn't on television at that time, full of jump cuts and current music. There was such a great energy to what we put together.

Q: Did any of the cast show up in the first actual series?

A: We found some really fun people who were perfect for the pilot. By the time MTV ordered the series nine months later, they were no longer right for the series. I always say that reality cast members are perishable, like fruits and vegetables. They only have a certain shelf life. You've got to get them at the right moment.

Q: Was it always going to be a different cast each season?

A: We weren't sure — we were so focused on making the pilot. MTV had decisions to make about who they were as a channel.

A lot of the reason for doing the show was to brand the channel, so it got tremendous publicity. And we tripled the normal MTV rating. This wasn't a music program, but it was giving their viewers something you could not find on CBS, NBC or ABC. People were making an appointment to see the show. It was starting to change the nature of the channel.

Q: Why did you settle on seven cast members?

A: We had six in the pilot. And when we were putting together the cast for the first season in New York, we couldn't decide on the six people, so we went with seven.

I think it's great that we did, because there's something stronger about an odd number. After we went [from a half-hour format] to an hour, there was a period when we switched to eight cast members. We did that for a few seasons and ultimately we decided that even with an hour to fill, eight didn't work. So we went back to seven.

When you had eight, usually you had four women and four men and you'd get this division in the house. By having seven, you don't get that division. It gives the show a different energy.

Q: Tell me about the show Starting Over.

A: Ever since we did The Real World, people had been asking, "Can you do The Real World as a daily show?" We always said no, because we shoot The Real World for 16, 17 weeks and make anywhere from 12 hours or 22 half hours out of that material. The story process is long and involved, and the editing takes a long time because you have to find the story.

For a show to run five days a week, it would have to have some structure to guarantee that you'd have a beginning, a middle and end to each episode. So we started talking about, "How would you do The Real World for adults? What if there were some adults who came together and life coaches could work with them to help them make a change in their lives?"

Q: How did Mary-Ellis's experience come into play?

A: Because she had come out of five-day-a-week daytime TV, Mary-Ellis had some really good ideas about how to structure the show. But she was facing a personal battle, a reoccurrence of breast cancer. And during that first season of Starting Over, Bonnie Bogard, one of our lead producers, was facing ovarian cancer.

Mary-Ellis was really pushing herself, and at the same time we were also shooting The Simple Life and that had its challenges when [stars Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie] weren't speaking to each other. A lot was going on. Mary-Ellis and Bonnie passed away [in January 2004]. It was a very challenging time.

Q: How did Mary-Ellis's death affect you?

A: For virtually the entire time Mary-Ellis and I were partners, we shared the same office. In the almost 17 years that we were together, we never had one argument. We had such respect for each other and such an appreciation of what each of us brought to the picture. It was an amazing relationship.

Q: How did you get involved with Keeping Up with the Kardashians?

A: My old friend Lisa Berger [an executive at E!] had a deal with Ryan Seacrest, and he brought Kim Kardashian in about doing a show. They had shot some tape with the family and there was a feeling that it would be interesting for E!

On a Friday we got a call from Lisa, saying, "We want to do this show, and we think you should partner with Ryan on it." Over the weekend, they put the tape that Ryan had shot up on our server so I could watch it, and I said, "Oh, my God. This is great. It's like a real-life sitcom. We should do this."

It's been an amazing experience. The family is incredible to work with. They are incredibly trusting of us, and the reason the show is so good is because they let the cameras roll on everything. They don't stop us.

Q: What has been your main contribution to Project Runway since you started as an executive producer on that show?

A: We were able to take a fresh look at it. They used to make more of a deal of the model selection. But the show is not really about the models, so we've taken that out. And at the very end of the show, when [host and judge] Heidi Klum is addressing the people who may be sent home or may win the challenge, I wanted to flash back to their design on the runway because I sometimes can't remember who had which design. So we put that in.

And the big reinvention for us came when Lifetime said, "Let's make the show 90 minutes." It allowed us to open up the show more, and as a result you get to know the designers a little better.

Q: Have you learned anything about human nature during your career?

A: One of the things that probably helped me is my experience growing up — first in Mississippi, then moving to upstate New York — where people made fun of me because of my Southern accent — then moving to England and being made fun of because of my American accent. Then moving back to America and being made fun of because of my British accent.

At some point, I realized I was gay. And as a gay person in America — certainly as I was growing up in the '60s and '70s — you felt like an outsider and you became very observational. You would have to gauge situations. You would have to judge character, whether you felt you could share who you were with someone. Then going to journalism school and learning about storytelling — all of those things prepared me for what I've done.

When you're making these kinds of shows, you're observing human nature.

I can sit in The Real World control room, watch what's going on and say, "She can only take this for about another two minutes, then she's going to run upstairs and throw herself on the bed. Let's get a camera up there and be waiting for her." You get good at reading people, and you can predict what's going to happen so you can have your cameras in the right place. Sometimes they'll surprise you and do the opposite of what you think, and that makes it fun and interesting.

Q: How do you feel about being called a pioneer of reality television?

A: Pioneer is better than grandfather! You know, it's something a lot of us making The Real World did together. There was no textbook for me, Mary-Ellis or George Verschoor, our producer-director on the first four seasons. There were a lot of people from the network — a lot of us were figuring this out. We were making a lot of mistakes, and luckily, we were learning from those mistakes. We all learned together.

Q: What advice would you give a young person who wants to produce or create reality TV?

A: Go to work for a production company whose shows you like. Learn everything you can. Do every job you can. At Bunim/Murray, we don't have a problem with someone working all phases of the show. They may do casting, go into production, then come back and work on post.

You need to know how to make a reality show before you pitch reality shows. Because you have to understand whether that show can be made, how you're going to make it and whether you can do it on a budget that will work for that network.

When we're hiring at Bunim/Murray, we look for really smart young people. I don't care if they've studied TV. If they have an English or philosophy or a history major, that's fine.

We can teach them what they need to know about running a camera or running audio equipment. There's very much an apprentice-type program here. Every year, 20 to 30 young people arrive here and start their careers.

Q: How would you like to be remembered?

A: As someone who always treated people fairly and who supported people in their efforts to be creative. And as someone who tried to not only make entertaining programming, but also programming that hopefully did some good.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, issue No. 5, 2018