INT. SABRINA'S BEDROOM — NIGHT

SABRINA

Salem, do you think the Council will grant the time reversal?

SALEM THE CAT

I'm the wrong witch to ask. They weren't very lenient to me. Sentenced to a hundred years as a cat. And for what?

SABRINA

I don't know. For what?

SALEM THE CAT

Oh, like any young kid, I dreamed of world domination. Of course, they really crack down when you act on it.

SABRINA

Wow. No wonder you're so possessive of the sofa.

— Sabrina the Teenage Witch , pilot

As a first-time showrunner and creator, I felt strangely confident going into the table read of the pilot episode of Sabrina the Teenage Witch.

I felt good about the script, the cast and the director. The only thing I did not feel good about was that I had to kick off the table read by giving a speech.

Public speaking is hard for me. My heart starts to pound and my voice gets quivery. I considered delegating the speech to someone else, but no one knew better than I did what made Sabrina special. After all, how many shows had a talking cat? Then it hit me. I had a plan.

The day of the read, the crowd filed in.

Viacom president Perry Simon patted me on the back and flashed me a smile. I waved to our director Robby Benson, who most people know as the star of One on One (if male) or Ice Castles (if female) or both (if me). At a nearby table, an animatronic cat sat stiffly on a wooden plank. Crew members and writers milled around. Actors flipped through their scripts.

Finally, the ABC contingent entered, led by the newly named president of entertainment Jamie Tarses and head of scheduling Jeff Bader. Jamie was the highest-ranking person in the room and when she took her seat, it was showtime. All eyes turned to me, then suddenly the cat came to life.

"Greeting, humans!" Salem called out.

The writers had composed a short, funny speech for Salem, who was voiced by fellow writer Nick Bakay. The cat welcomed the group, then after a few lines, started to cough and hack trying to expel a hairball. With his last breath, Salem turned the table read over to me.

After Salem's intro, the pressure was off. I thanked the network and studio for their support, the crew and writers for their work, and lastly, I thanked the actors.

"You're all amazing," I said. "I love this cast. But please know, if you complain too much…" My voice trailed off as I gestured toward the cat, which sprang to life again. The implication was that the actors could be replaced by fancy puppets. People laughed.

I nodded to Robby, who read the opening stage direction: "INTERIOR: SABRINA'S BEDROOM — NIGHT." We were off. About 24 minutes later, Robby read, "FADE OUT. END OF SHOW." Everyone applauded. They always do, so I didn't read anything into that.

The executives huddled in a corner while the writers, production staff and actors headed to stage. While I waited for notes, I thought about how far we'd come in only four months. It all started when my new agent, Abby Adams, called to ask if I'd been a fan of the Sabrina the Teenage Witch comic books as a kid. I had.

Part of the Archie universe, Sabrina was created by George Gladir. Viacom Productions turned the premise into a cable movie written by a group led by Barney Cohen. That movie was edited into a four-minute presentation that Viacom shopped to networks. Ted Harbert, then president of ABC, saw Sabrina as a good fit for the family-friendly TGIF lineup and ordered 13 episodes. Easy!

Not so fast. Jonathan Schmock, a gifted writer and artist, wrote a pilot script. He was slated to run the show as soon as he wrapped up his job on the already-canceled Brotherly Love. Then in a surprise move, the WB picked up his show and Jonathan was no longer available.

After a season as supervising producer on Murphy Brown, I had jumped into an overall deal at 20th Century Fox Studios. Peter Roth, one of the nicest and most successful executives around, signed me to an 18-month contract to create sitcoms. The studio paired me with novelist Doug Coupland to develop his book Microserfs into a show set in the tech world. We pitched our concept to the head of the Fox network.

"This is the most thought-out pitch I've ever heard," he told us. "And I didn't understand a word of it."

Microserfs crashed, but I rebounded and sold a concept to the WB about two high school besties with a cable show. Prudy and Judy was picked up to pilot, and we cast Jackie Tohn and Laura Bell Bundy, who later originated the role of Elle Woods in the musical Legally Blonde. The WB passed on the series, which made me sad, but also freed me up to meet on Sabrina.

As the new Sabrina showrunner, I was given leeway to rewrite Jonathan's pilot script, which centered on Sabrina screwing up her driver's test. I refocused the story on Sabrina discovering her magical powers and worrying about her social status.

"I don't want to be special," Sabrina (Melissa Joan Hart) insists to her warlock father. "I want to be normal ."

"I understand," her dad responds. "But that ship has sailed."

On her first day at school, Sabrina makes a series of mistakes. She gets hit in the head by a football in front of the boy she likes. She fails a pop quiz. Finally, she loses her temper in the cafeteria and uses her magic irresponsibly. The second act opens in the Spellman kitchen. Sabrina enters, panicked, holding a pineapple.

SABRINA

I hate being a witch. I just turned the most popular girl in school into a pineapple.

HILDA

Chill. I can fix this. (TAKES A CLEAVER OUT) Chunks or rings?

ZELDA

Hilda, there are other ways.

HILDA

Wedges?

Aunt Zelda turns the cheerleader, Libby, back into her human form. Libby isn't sure what just went down.

"You did something to me," she says. "You sent me somewhere. It was small and smelled like Hawaii."

Libby storms out, promising to destroy Sabrina's reputation. And she has the power to do it. "She's a cheerleader," says Sabrina. "No one has more credibility."

Desperate to undo the disastrous day, Sabrina petitions the Witches Council to turn back time. This scene set up the metaphor of the entire series: being a teenager means coming into your powers, but being an adult means learning to control them.

The council — I cast magicians Penn and Teller as council members Drell and Skippy — turns down the request. Sabrina has no choice but to go back to school and face Libby's ridicule.

"Fine. I surrender," Sabrina says as she heads off the next morning. "I guess every school needs a weird kid. Might as well be me."

"I was the weird kid!" Hilda calls after her, cheerfully.

It made my heart beat faster to hear Caroline Rhea deliver this line in such a chipper voice. I was the weird kid, too. Sabrina was my attempt to create a show that my teenage self would have watched.

In the final scenes, Aunt Hilda confronts Drell and forces him to give her niece a do-over. Sabrina makes the most of her second chance. She catches the football, aces the quiz and doesn't turn the cheerleader into a pineapple. At the end of the school day, Sabrina races home, triumphant.

"Yay! I'm normal!" she declares. "Gotta go tell the cat!"

Back at the pilot table read, the ABC huddle broke and Jamie Tarses delivered the notes. She opened by saying she enjoyed all the performances. She liked the animatronic cat. She thought the story worked fine. She did, however, have one "fairly major note." I tensed. Jamie felt there wasn't enough conflict between the aunts. She asked me to describe each one.

"Zelda's the straight man: logical, restrained and stable," I said. "Hilda's the wild card: emotional, blunt and an incurable romantic." Jamie thought we needed to push the contrast more, especially in the aunts' attitudes toward their niece.

She pitched an idea: What if one of the aunts didn't want Sabrina living with them? Jamie's pitch definitely created more conflict, but it felt off to me. I'd been primed to nod and say, "Let me look at that," but I couldn't see doing any version of this pitch.

"That seems sad," I said. "Sabrina's a teenager. If she's not with one of her parents, and the aunts she's living with don't want her there, how can we laugh?"

Jamie and I went back and forth. I kept hoping someone from Viacom would back me up, but arguing against a network president is a lonely task. We reached an impasse. I sensed it was my cue to say, "Okay, I'll try it that way," but before I got the words out, Jeff Bader jumped in and uttered the four most beautiful words in the English language: "I agree with Nell."

Most networks present as a monolith, so Jeff offering an independent opinion was completely unexpected. His speaking up broke the deadlock.

"Fine," Jamie said, ready to move on. "Leave it." I will always be grateful to Jeff for his creative support at such a crucial moment. From then on, the pilot shoot went smoothly, thanks in large part to Robby Benson's creativity, preparation and expertise. Robby even did double-duty when he agreed to play Sabrina's dad and had to direct himself.

Closing in on our premiere, Sabrina was flying under the radar as ABC focused its promotional efforts on Clueless, an adaptation of Amy Heckerling's perfect movie.

I worried that reviewers who were — and still are — mostly male might not appreciate our series and its three female leads. Some reviewers did dismiss the show, calling it "daft" and "borderline funny-dopey." But a few heavy hitters, like Pulitzer Prize winner Tom Shales, were charmed.

Sabrina premiered on Friday, September 27, and the next morning at nine, I stood in my kitchen, dialing into the ABC overnight ratings hotline. TGIF shows typically received a 10 to 14 audience share. The voice on the hotline droned through the eight o'clock shows. Then: "Eight-thirty, ABC, Sabrina the Teenage Witch, premiere, 20 share."

I screamed. Over the weekend, I dialed that number over and over and never tired of hearing that "20 share," which translated to over 18 million viewers. Within weeks, my hero Jeff Bader was telling Entertainment Weekly, "Sabrina is the little show that could."

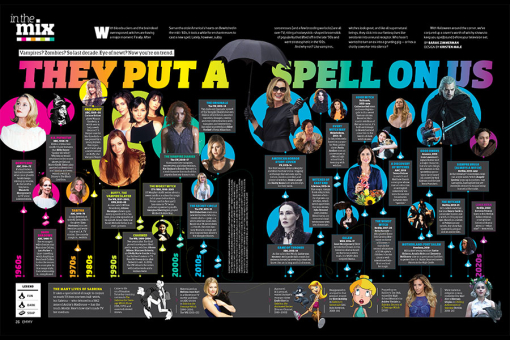

The network flipped our timeslot with Clueless. We stayed in the nine o'clock slot and finished 30th out of 155 shows for the 1996–97 season. More importantly, the Valentine's Day episode fulfilled a dream of mine to get mentioned in TV Guide's "Cheers & Jeers" column. Even better, it wasn't a jeer. ("The campy spell cast by Sabrina was enchanting.")

As showrunner, I got to build the writing staff and hired coexecutive producer Norma Vela and supervising producers Carrie Honigblum and Renee Phillips. I'd never worked on a show with so many high-level women. Still, I should have been more inclusive.

The Sabrina room had some diversity, but we didn't have any writers of color. I'm aware of all the excuses I could make to justify the homogeneity because they've all been made against me on male-centric shows. I had the opportunity to include more voices, and I didn't make enough of an effort. That was a mistake.

The cast was all white, too. Early in the pilot process, my CAA agents pitched Cicely Tyson for the part of Aunt Zelda. Tyson is a Tony-and Emmy-winning actress, and I should have jumped at the suggestion. Instead, I said that we were already zeroing in on Caroline Rhea and it wouldn't make sense for the two to be sisters.

"It's a world of magic. Maybe one sister is black," my agent said.

It would have been an interesting and bold move, but I didn't pursue the idea.

The rest of the writing staff included Salem's alter ego, Nick Bakay, who went on to a stellar career in TV and movies. Frank Conniff was better known as "TV's Frank" from Mystery Science Theater 3000. Rachel Lipman had written a classic Rugrats episode. I leaned heavily on coproducer Jon Sherman, who went on to become an executive producer of Frasier.

On set, Paul Feig was hysterical as Sabrina's biology teacher, Mr. Pool (first name: Gene). Watching Gary Halvorson direct six episodes was a master class in how to run a set. Editor Stu Bass made every show funnier. (Hey, I never got to make an Emmy speech, so I'm doing it here.)

The show's tone tended to be my favorite mixture of grounded and absurd. Sabrina's high school football team was nicknamed "The Fighting Scallions," a misprint of "Stallions" that the school couldn't afford to correct. We wrote in a giant flan and a lint monster that leapt out of the dryer.

We hired guest stars like Bryan Cranston, Henry Gibson and Donald Faison. Raquel Welch played Sabrina's fun-loving, thigh-high-leather-boot-wearing Aunt Vesta and helped deliver the show's highest-rated episode.

Beth Broderick and Caroline Rhea made a fantastic team as Aunts Zelda and Hilda.

Beth anchored the plots and accepted the necessary task of laying out exposition. Caroline took the show to comedic heights. Her upbeat delivery allowed her to say the most insane lines with complete conviction. When Hilda and Drell start a relationship, she explains that if he breaks a date, he always sends a pot roast, which magically appears in the oven.

"Flowers wilt," Hilda says. "Say it with beef."

The original order for 13 Sabrina episodes expanded to 22, and then the network added two more.

We had some turnover in the writers' room and with five shows left, I hired my friend Barry Marx as a staff writer. Barry had never written for TV, but he'd worked on a video game with Penn & Teller and I knew he could do the job. Barry moved out from New Jersey, subletting an apartment near the Hollywood sign.

By the final two episodes, I was exhausted. New shows are a lot of work, and having a green staff meant a lot of rewriting. Executive producer Liz Friedman once summed up the experience: "Running a show is like being beaten to death by your own dream."

My contract had been for a season, and Viacom offered me a generous — but not perfect — deal to extend for another. I was on the fence about returning for a variety of reasons, and I didn't have the psychic energy to sort it out while still in production.

My goal was to finish strong. The penultimate episode was built around Sabrina and her classmates visiting Salem, Massachusetts. I'd written a detailed outline that the studio and network approved on a Friday. The table read was on Monday, which meant I had to write the script over the weekend.

That Friday evening around seven, I sent the writers home. One lingered.

"Is there anything I can do to help?" Barry asked.

"Thanks," I said. "I'll be fine."

Barry flashed me a smile. We said good night and I returned to the set, where we shot for another couple of hours. When the set wrapped, I headed home to my husband, Colin. We were already in bed at 11 when the phone rang.

It was Penn in Vegas. Barry's girlfriend in New York City had just called. She'd been talking to Barry when he suddenly exclaimed, "Ow, that really hurts!" and then cut out. She tried calling back, but the line was busy.

She didn't know how to call 9-1-1 from out of state, so she called Penn, who was calling Barry's friends in L.A. Another friend, Rich Nathanson, had already reported the emergency. Colin and I jumped in the car.

Police cars were outside the apartment complex when we arrived. Rich was standing on the lawn, his face contorted. We cried as coroners carried a body bag to the van.

We later learned that Barry had suffered a rupture in his aorta, a congenital defect. He was 40. That was Friday night. I spent Saturday with friends and my family. On Sunday, Jon Sherman came to my house and together we turned the Salem witch trial outline into a script.

The table read on Monday was a blur. Later that afternoon, I stumbled through a call with Barry's parents, telling them how sorry I was and how much we would miss him. I felt guilty that the job had moved him 3,000 miles away.

That same week, my lawyer called to say Viacom was pushing for an answer on their latest offer. I asked if we could hold off until the season wrapped. Viacom's business affairs department said no.

And this is what I learned: If you're on the fence about signing up for an all-consuming project and that week you watch a friend carried out in a body bag, you will determine that life is too short. You will make the choice that allows you to spend precious time with the people you love most. I walked away from Sabrina.

There are days when I regret that decision. There were compelling creative and financial reasons to stay. There were also unpleasant aspects of the job that may not have been fixable.

Mitch Hurwitz, creator of Arrested Development, once compared running a show to "piloting an airplane while the passengers throw rocks at your head." I know that feeling well. You want to turn around and shout, "Hey! If I go down, we all go down."

My friend Miriam Trogdon took over as Sabrina showrunner, and I appreciated that Viacom hadn't replaced me with a male writer. (Eventually, that happened.) Miriam called me to check in.

"Here's my recommendation," she said. "Never watch the show again."

I took her advice, although once on a plane, I caught a scene from a much-later season. Sabrina and her aunts were arguing in the Spellman kitchen and the characters' attitudes were unrecognizable to me. The only things that felt familiar were the little teacup handles on the kitchen cabinets that I had picked out with the set decorator for the pilot.

Sabrina continued for three more years on ABC and two on the WB. Ratings were never as high as that first season, but they remained strong enough for the show to sell into syndication.

In 2016 the show celebrated its 20th anniversary, and a reporter reached out to women who'd grown up watching it.

Lena Dunham, who was 10 when the show premiered, shared this: "Sabrina the Teenage Witch was truly formative for me on every level — it was subtly radical feminist storytelling, never denying the power of sisterhood or the magic of a teenage girl. Sabrina had agency, she had spunk, and it took the form of magic. It makes me laugh to this day. I feel lucky it was on TV for girls like me."

Lena's words made me think back to that table read where I fought to keep the aunts welcoming of their niece. "Never denying the power of sisterhood" turned out to be a key to our success.

As a science-fiction fan, I fantasize at times about visiting a parallel universe where I'd stayed on as Sabrina's showrunner. I'd like to meet alt-Nell and ask if it was worth navigating the obstacles to create bigger flans and lintier monsters. But mostly I want to go to that parallel universe and spend time with alt–Barry Marx, who is still alive and well and flashing his sweet smile.

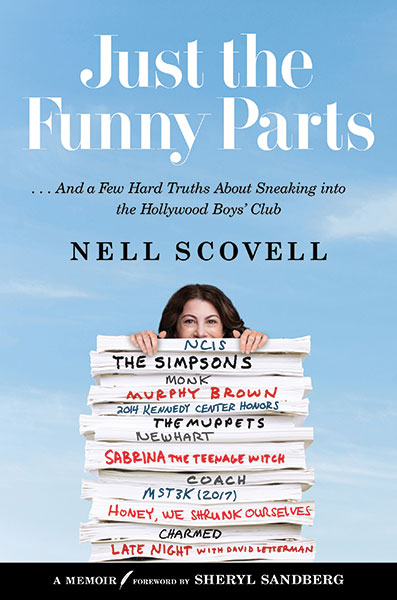

Adapted from JUST THE FUNNY PARTS: …And a Few Hard Truths About Sneaking into the Hollywood Boys’ Club by Nell Scovell. Copyright © 2018 by Nell Scovell. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 9, 2018