The Masked Scheduler has been unmasked!

Preston Beckman, the head of NBC’s scheduling in the Must-See TV era and executive vice-president of strategic program planning at Fox during the American Idol epoch, started tweeting about TV anonymously under that moniker in 2008. Even though he officially retired from the business in 2015, Beckman keeps tweeting — and he recently launched a new column for the website TV By the Numbers.

Recently, emmy contributor Bruce Fretts spoke with Beckman about his brilliant career and the future of TV.

How did you originally get into TV? Did you watch a lot as a kid?

Oh, I loved television. My earliest memories involve Milton Berle and Superman. I grew up in New York, and my father owned a grocery store on the Lower East Side. He would get tickets for Howdy Doody and Wonderama. So I was on all those shows. Yeah, I’m old.

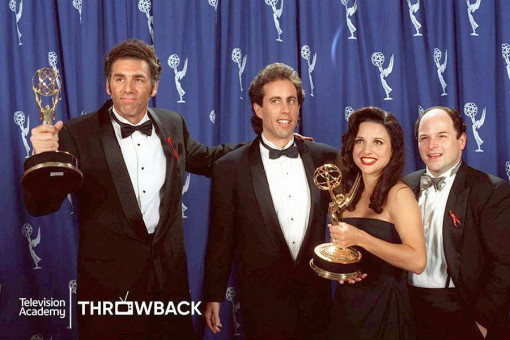

At NBC you were an early supporter of Seinfeld, but the show took several years to become a hit. What gave you such confidence in it?

It was different. We had been doing shows like The Facts of Life and Diff’rent Strokes.

[NBC entertainment president] Brandon Tartikoff wasn’t a big fan of it. We put the pilot on the air on a Thursday night, after the season was over. The number popped. I wrote a memo to Brandon showing how it performed in the markets, because he had said it was too Jewish and too New York. I pointed out that it did not skew New York.

We wound up ordering six episodes and putting them on Thursday, late in the season. There was still not a lot of passion. We ordered 13 more — those didn’t come on until January. After Brandon was gone, we screened more episodes.

I remember Bob Wright said, “This show is so funny! Why isn’t it on the air?” And I said, “Well, no reason anymore!” We moved it to Thursday behind Cheers. I got a lot of calls from people, saying that I was crazy, that it was a small show, that it was not going to work. I just thought, “Maybe I’m wrong, but I think this is the real deal.”

You had such a great run with NBC through the ‘90s. What prompted the move to Fox in 2000?

Well, success breeds failure. [Former NBC entertainment presidents] Warren Littlefield and Don Ohlmeyer were gone by then. I thought, “This isn’t fun anymore.” I just figured it was time for me to move on.

To be honest, I always wanted to work at Fox. They were the renegade network, so they saw me as the veteran broadcaster who’s going to come in and show them how to win. There was a lot of fear of success over there. They didn’t want to be one of the big boys. They were different. But you gotta win. So, for me, it was a good move.

Then American Idol came along in 2002. How did you manage that phenomenon?

Very early on, we made some decisions about the content. It was originally portrayed as a very nasty, dark show. We changed up the promos to make it more aspirational. It was a post–9/11 show. It was at a point where people wanted to feel like they were in control of something: you can pick the next superstar!

We decided to make it feel more like an event by doing it once a year. Then when we moved it from summer to January and debuted it in the same timeslot as 24, I used to call it the shock-and-awe week. We would start on Sunday night, usually after a football game, with two hours of 24, then two more hours of 24 on Monday, then four hours of American Idol over Tuesday and Wednesday night. By the end of the week, the other guys would throw in the towel.

Why did you develop the Masked Scheduler persona?

When Twitter came along, I thought, “Well, I could go on as me, but that might not be wise because my bosses might tell me to shut up.” Also, I thought it gave me more freedom to express myself. I never said who I was. Everybody kept saying, “It’s you!” and I had to deny it. I’ve never come out on Twitter and said it’s me. Some people still don’t know to this day.

What do you make of the current landscape? Is there too much TV?

I laugh a little bit at the term “peak TV,” because it’s all about platforms and feeding the beast. If you’re a cable channel or a streaming platform, you better have one or two signature shows. You need content. The more content you need, the more you’re forced to allow people to express themselves in ways that aren’t necessarily ratings-driven.

But at some point, there will be a shakeout because there’s only so much consumers are going to pay.

How has the TV game changed?

When I started, it was a cutthroat, zero-sum game among three or four players. You really had to think about counterprogramming and how to put together a schedule. At some point, it became, “Worry about yourself.” You still need to put a schedule together, but you don’t have to attack the other guys. Everybody carves out a little bit.

With time-shifted viewing, is everyone a scheduler now?

Yeah. Everybody is going, “Okay, after dinner I’m going to sit down for three hours — what am I going to watch? I can watch something live, I can look at what’s on my DVR, I can go on Hulu.” Everybody does some combination of that. Then you throw in sports!

For everybody, there are a couple of shows that, if they don’t watch live, they watch as close to live as possible. I would go crazy if I didn’t watch Walking Dead or Game of Thrones within a couple of days. With Twitter or Facebook, I’d better watch these shows before somebody spoils them for me.

And, on top of all this, everything’s available now. I started watching The Wire years after it had ended. I came in the middle of Breaking Bad, and to this day my son still screams at me, “Dad, when are you going to watch the first three seasons?” But anything from the past that you want to watch, it’s there. Which is good!

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 5, 2017