Oddly perhaps, relatively few prominent stand-up comedians have scored powerhouse success in sitcoms. In the 1950s, only Jack Benny, George Burns and Gracie Allen, and Danny Thomas accomplished the feat. The 1960s saw even fewer noteworthy stand-ups cross over into sitcoms. Don Adams, premiering in Get Smart in 1965, was one exception. Then, in 1971, came Redd Foxx in Sanford and Son.

It wasn't until the 1980s and '90s that stand-up catapulted a cluster of stars to sitcom fame: Jerry Seinfeld, Tim Allen, Ellen DeGeneres, George Lopez and Ray Romano among them. But in the 1970s, only one stand-up stands out for making the sitcom their biggest, most sustaining career success: Bob Newhart.

With a low-key delivery and a slight put-on stammer, he starred in two long-running CBS series: The Bob Newhart Show (1972–78), which ran for six seasons, following up with eight seasons of Newhart (1982–90). Distinguished by an absence of kids and snark, both shows brought a breath of urbane, if not quirky, fresh air to the sitcom genre.

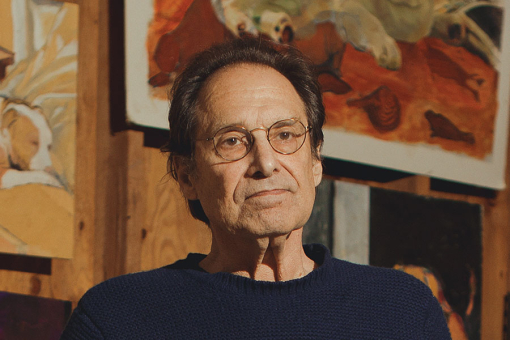

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of The Bob Newhart Show's premiere. The comedian, now ninety-two, recalls his years on the series as among his happiest. He played mild-mannered psychologist Bob Hartley, whose clients were an array of suitably neurotic folks. One of his creative therapies was a "Fear of Flying" workshop.

Set in Chicago — Newhart himself was born in adjacent Oak Park — the show had Bob Hartley married to assertive elementary school teacher Emily. Suzanne Pleshette played her as sexy in a wholesome kind of way.

Costars included Peter Bonerz as orthodontist Jerry Robinson and Marcia Wallace as the office suite's sarcastic receptionist, Carol Kester Bondurant. Comic traffic was largely supplied by the patients, played by Jack Riley, Florida Friebus, Renee Lippin and John Fiedler. Another fan favorite: Bill Daily as airline pilot and friend of Bob, Howard Borden.

In Newhart's next series, Newhart, he played a writer, Dick Loudon, who's opened an inn in Vermont, where he's surrounded by assorted pastoral eccentrics. This time, Mary Frann was his wife, Joanna. Julia Duffy costarred as Stephanie Vanderkellen, the haughty maid. Peter Scolari played Michael Harris, the producer of a local talk show that Newhart hosted. And Tom Poston, who'd played an old college buddy in the earlier series, returned as handyman George Utley.

Before Newhart found comedy, he worked as an accountant at the United States Gypsum Corporation in Chicago. Bored with the gig, he and a buddy would ad-lib funny bits on the phone. It wasn't long before the two were recording these and aiming for a career in comedy, mailing them to a radio station. Nothing popped, though, so Newhartwenton to adifferentday job, writing commercials at Fred A. Niles Productions. On the side, he penned jokes for established comedians.

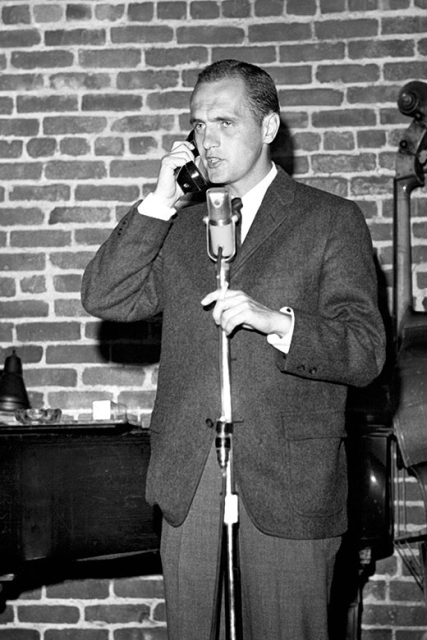

Then luck cut in: a friend introduced him to Warner Bros. Records, which wasted no time in signing him to a contract. His first comedy album, The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart, released in 1960, made him a star overnight. Not only was it his first LP, it was a recording of his first performance in a nightclub.

Newhart was part of the so-called "new wave" of stand-up comedy, along with Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce, Shelley Berman and the team of Mike Nichols and Elaine May. Their social satire skewered sacred topics and mostly eclipsed the one-liner joke style that had dominated since vaudeville.

With his soft voice and squeaky-clean self-written material, Newhart wryly parodied the corporate mentality. His comedy was usually wrapped within one-sided phone conversations. Two of the most popular routines were about a press agent coaching Abraham Lincoln on his Gettysburg Address and "The Submarine Commander," a call with the incompetent chief on a nuclear sub.

In 1961, he segued to television with a variety and comedy program called The Bob Newhart Show (his first with that title). Though it nabbed an Emmy and a Peabody Award, it failed to attract a large audience and wrapped in 1962 after twenty-seven episodes. He stayed busy, appearing in TV variety shows and made-for-TV movies and, of course, doing stand-up.

Ten years would pass before the second The Bob Newhart Show emerged, this time as a sitcom. Produced by MTM Enterprises, the series scored robust ratings in the Saturday night slot right after the popular The Mary Tyler Moore Show. (The network even dubbed it "Stay-Home Saturday.")

In the '90s, Newhart tried television comedy again, with Bob (1992–93) and George and Leo (1997–98), but neither caught on. He's had recurring or guest-starring roles on Desperate Housewives, The Big Bang Theory (for which, in 2013, he won an Emmy) and NCIS, among others. He's also appeared in some fifteen feature films.

In addition to the Peabody and the Emmys, Newhart has won The Mark Twain Prize for American Humor and three Grammys. In 1993, he was inducted into the Television Academy Hall of Fame. Sixty-one years after his initial foray into series television, a proud Newhart looks back in this candid interview.

You had a huge stand-up career before starring in your 1961 series, The Bob Newhart Show, a variety program. Comedian George Gobel, who appeared in early TV, was one of your biggest influences. Please explain.

He showed that you can be on television and don't have to be this loud guy or wear women's dresses. And of course, I was a great admirer of Jack Benny. People always said I got my timing from Jack. But you don't get timing from somebody. It's something you hear in your head. Jack was a great influence, though. I've always thought Jack was the greatest comedian I'd ever seen work. He wasn't afraid of silence. He would take the time it took to tell a joke, no matter how long, because he knew it was going to pay off. Other comedians would panic.

But every good comedian I ever saw on The Ed Sullivan Show or The Steve Allen Show was an influence. You learn from everyone.

You once said that you have a dark sense of humor. Where does it show up?

I tend to find humor in macabre places. Most comedians do. When you're in a writers' room and a tragedy happens [somewhere], it's like a contest — who'll come up with the first joke about the tragedy. You try to portray the most insensitive person you can think of who'll be totally insensitive to whatever just happened.

But you haven't used black comedy in your stand-up or sitcoms, have you?

Steve Martin said I did! There are rude scenes in my Abe Lincoln routine: someone [a press agent] wasn't showing quite the proper respect, maybe, to the greatest president we ever had by telling him how to arrange his speech. And "The Submarine Commander" [routine] had some dark areas.

How was the experience of starring in your variety show?

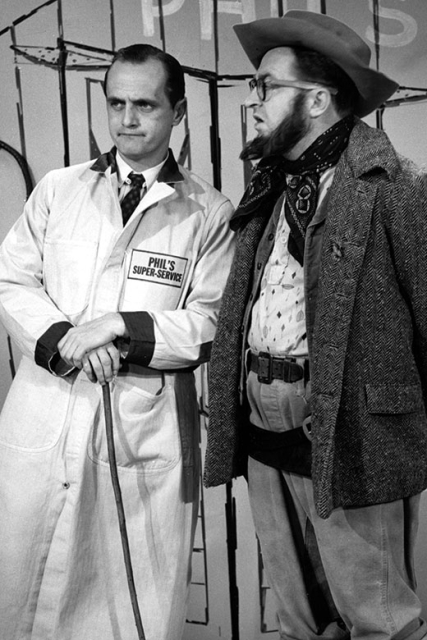

I felt the quality of the monologue was being hurt because we were doing thirty-three shows, and we didn't have time to give it the attention it needed. We usually did a comedy sketch with a guest star, like Charles Bronson or Dan Blocker. I didn't think I was very good in the sketches — in stand-up, I pictured the person on the other end of the phone [as opposed to working with an actor]. So I said to myself, "You're going to have to get better at this if you want to last very long in this business."

The show was on for only one season. What happened?

We received a Peabody Award. As far as being renewed, we were on the bubble. But NBC didn't want to be accused of canceling a Peabody Award show. And then the network and I had a falling-out. They had some conditions for renewing the show, one of which was to replace the announcer, Dan Sorkin, who was a friend of mine. He was responsible for my getting my [comedy album] recording contract. So I said no.

At that point, did you aspire to do a sitcom?

After the variety show, I went on the road doing stand-up for twelve years, all over the country. It was kind of disruptive to my family life. So when I was approached by Arthur Price, who was one of the founders of MTM Enterprises and my manager at the time, about doing a sitcom, I thought it would get me off the road and into some sort of normal life. By then, I'd had twelve years of watching television to try to get better at it. I would watch good people and what they did.

In fact, I did that with stand-up. Before I ever thought of going into it, I watched The Ed Sullivan Show, and when a comedian came on, I'd think, "Why did he pick that word?" Or, "I see what he's doing. He said that earlier, and he's playing back on it." So I watched comedians analytically and learned from some pretty good people.

Once you made the deal to star in The Bob Newhart Show, what kind of input did you have?

I had input into the concept of the show. I worked with [cocreator] Lorenzo Music, who had been a writer on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, and he and I had worked on a couple of projects together. I'd also worked with [cocreator] Dave Davis. So we sat down and said, "What's going to be my profession?"

They were familiar with my record album and the phone conversation routines I did. So they said, "Bob's a good listener. How about a psychiatrist?" I said, "A psychiatrist deals with pretty serious mental problems. It's kind of hard to get any humor out of manic-depression!" So we settled on psychologist.

How did Suzanne Pleshette get cast as your wife?

Arthur Price saw her on The Johnny Carson Show. He said, "What about Suzanne Pleshette?" I said, "She'd be great. But she has a movie career. Do you think she wants to do television?" As it happened, Suzie wanted to do a TV show because she was pregnant and not looking to travel at all. The chemistry between us was just great."

What about casting the other main parts?

There were two pilots. In the original, I was a psychologist and Peter Bonerz was Jerry, a more adventuresome psychologist. In the final pilot, he became an orthodontist.

Babe Paley [the wife of CBS president Bill Paley] had seen Marcia Wallace on The Merv Griffin Show and suggested that she might be a good addition as a receptionist. Of course, what Bill Paley wanted, Bill got. A live show throws some professionally trained actors. So I knew I had to [cast] people who were familiar with working in front of an audience.

Peter, Marcia and Bill Daily [Howard Borden], who was a struggling stand-up, all had stage experience. So I knew they wouldn't be thrown by a live audience.

How important was it to you to have a live studio audience?

You learn so much because they tell you [what works]. Very often there's an instant rewrite and the writer will say, "We're going to try this." It's dangerous but fun.

Most family sitcoms of the time had children. Why didn't yours?

I said, "I don't want to have kids. That's not the kind of show I want to do." I didn't want to be the lovable dolt who keeps getting himself in scrapes, and the kids and his wife huddle together to figure out how to get Daddy out of this scrape he's gotten himself into. That wasn't the role I wanted to play on television.

Did the network push back?

No. They understood. My wife, Emily, had her career as a teacher, and I had mine. I think that was part of the charm of the show. It was about two adults."

I understand that you, and others, taped your lines to various props because they were hard to remember. True?

Yes. They were changing all the time. I considered it an art form to hide the lines. We'd come in on Monday, do a table read, then rehearse for two days. On Tuesday we had camera blocking, and the rewrite would take place between Wednesday night and Thursday morning. So you never had time to learn anything till Thursday, and even that was subject to change.

I know it was very unprofessional to hide my lines, though Brando did it. I understand he even hid them filming The Godfather.

Where did you hide yours?

Everywhere but on the foreheads of the other actors, though I considered that. But it wouldn't have been fair to them because we'd be constantly erasing!

You and Emily routinely had scenes chatting in bed. That was unusual for couples in sitcoms back then.

We had them because Suzie and I had great chemistry. She was a marvelous foil. I think we were the first sitcom where a married couple shared the same bed. They were finally going to explain to America that sometimes married people stay in the same bed!

What was the tone on the set? Always joking around, or were you all laser-focused on the work?

One day Tommy Poston's wife, Kay, came to the set when we were having blocking and after that, we had lunch. He told me that when he and Kay were driving home, she said to him, "Please don't ever tell me how hard you work because all you people did was laugh!" That was true on both shows. We had a good time, and that translates to the screen.

Did the cast of The Bob Newhart Show usually have lunch together?

The men would drift off by themselves, and the women would drift off by themselves. But we'd see one another at the MTM commissary. Ed Asner, Ted Knight [of The Mary Tyler Moore Show], the St. Elsewhere people and the Hill Street Blues people were all there having lunch. It was one of the great lots — small and friendly. MTM made it a wonderful place for actors, writers and [other] creators.

How was the food?

It was a commissary! We didn't have a lot of weddings there. Let me put it that way.

While appearing on The Bob Newhart Show, were you also doing stand-up?

I never quit stand-up. When we went on hiatus, I'd play Vegas and Tahoe or The Front Row Theater in Cleveland. I loved doing it.

And I'd do the warm-up for the TV show audience. I always thought it made them feel kind of special, like they weren't there just to laugh and get the hell out. Also, things would happen during the taping that you'd do jokes about — people would blow their lines. Joking about things like that created a warmer feeling.

Do you have any favorite episodes?

There's one where I come into the reception area and Marcia says, "You have a new client. I put him in your office." So I open the door, and there's this ventriloquist and his dummy, who's lying on the coach.

The ventriloquist says, "Walter wants to go out on his own. He feels he hasn't grown." So then the dummy and I talk privately. It was so much fun to play this.

The hardest part was that the voice wasn't coming from the dummy, of course; it was coming from the ventriloquist. But you're trained to look at where someone's voice is coming from. So I had to remind myself that when the dummy was talking, to look at the dummy.

There used to be so many ventriloquist acts on TV shows years ago.

Yes, on Sullivan and other variety shows.

Speaking of Ed, you were on The Ed Sullivan Show many times. What are your memories?

It was a tremendously powerful show. You never knew where you were going to wind up in the show because Ed kept changing [the order]. There was an afternoon show and then an evening show. Between the two, you'd go to your dressing room, such as it was, in the Ed Sullivan Theater, which, I think, had been an old vaudeville house.

They would start out by telling you, "You're on between, say, Mickey Rooney and the McGuire Sisters." Then they'd knock on the door and say, "Now you're on after [the puppet] Topo Gigio." Then just before the shows started, there was another knock, and they'd say, "You're after Elvis!" So you never knew. It was all in Ed's head — the way he saw it.

Comedian Jean Carroll, who had a contract with Sullivan, told me that very often, at the last minute, Ed would tell her to cut some of her act. Did that happen to you?

No, because with a routine, it isn't just cutting out a joke. If Ed told Henny Youngman to cut, then Henny would just drop two jokes and go to the end. But when, for example, I was doing the press agent for Abe Lincoln routine, I just couldn't suddenly go to Ford's Theatre jokes. You had to stay in character.

Why did The Bob Newhart Show end?

We'd done six years. It was live, so you were doing a half-hour play every week. Doing that for six years is tough. And I had this feeling, having watched other shows, that I would rather go off [the air] a year before than a year too late. I'd seen shows that should have left a year before. I didn't want that to happen.

When you began your next sitcom, Newhart, what was it like having a different onscreen wife and a different profession?

I said to Mary Frann [who played wife Joanna], "You've got a really tough job because Suzie and I had this wonderful chemistry. Many people are going to compare our relationship to that one." And it was always tough for Mary. What Suzie and I had was very special.

How was it working with Julia Duffy, who played Stephanie the maid?

She was very important to the success of the show. The first two years I didn't think we'd found it as a show. Then Julia came in, along with Peter Scolari, and it made the show work. Julia was marvelous. Her character was from a wealthy family. What the hell was she doing as a maid in Vermont!

The last episode of Newhart was memorable: Bob wakes up in bed next to Emily, your wife from The Bob Newhart Show. He says he's just had a dream of being an innkeeper in Vermont. Is it true that that idea came from your real-life wife, Ginnie?

At a Christmas party, I said to her, "Honey, it's the sixth year. I think this is going to be the last year of the show." She said, "If it is, you should end it with a dream sequence because there were such inexplicable things that went on in the show." I said, "That's a great idea."

It turned out that CBS and I straightened out the problems we had, and the show went on for two more years. Then the time came, in the eighth year, when again I decided that I didn't want to go off a year too late. I gave Ginnie's idea to the producers, and they did a wonderful job of wrapping everything up.

And that, as far as you were concerned, would be the final chapter in your TV series career?

No. I always knew I'd be coming back to television. I loved the life. We had a normal kind of life. You went in at ten o'clock in the morning and would rehearse and rewrite scenes and change things. On Friday, you'd go in at noon and would be off at eight-thirty at night. We didn't have those fourteen-or sixteen-hour days that you hear about.

Tell me about your next sitcoms. There was George and Leo.

It didn't work. It was well-written. Before that, I did Bob. That didn't work, either. We tried to take the elements of The Bob Newhart Show and Newhart, but it was a different time on television.

In a guest-starring role, you did three episodes of Desperate Housewives, playing Morty Flickman, estranged partner of Lesley Ann Warren's character. How was that?

A kick. Usually it takes half a year for a show to take off, but that one took off from the beginning. It was the hottest show on TV.

Then you did six episodes of The Big Bang Theory, playing Arthur Jeffries aka Professor Proton. How did that come about?

I knew [writer-producer-director] Chuck [Lorre] from the MTM lot. He was one of the writers on Roseanne. He'd call me from time to time. I'd tell him, "I'd love to work with you, but I don't think that's the show."

Then, in about 2012, he called and said, "I've come for my annual turn-down." I said, "No, I like the cast and the writing on The Big Bang Theory." He said, "Let me write something and see if you like it." So he wrote this great character. It just caught my rhythm, kind of my view of life.

And now you're Professor Proton on Young Sheldon, The Big Bang spinoff, as well.

My voiceover is.

Do you hope to star in another series of your own?

Oh, no, no, no. I'm ninety-two. I've had my time. It's time for the young people. I had a great run. I had a great life on television.

How do you keep in shape?

Good genes, I guess. And I've got a physical therapist who comes in once a week; we exercise together. Every day I'm on the bike, and also doing exercises. I have a wife who wants to keep me around — for some reason!

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #6, 2022, under the title, "All About Bob."