On an idyllic spring day in Marina Del Rey, California, Tom Hugh-Jones — ready for a day of whale-watching — steps aboard The Legend, a 70-foot vintage yacht.

The Emmy Award winner (for his work on Planet Earth II) is the executive producer of National Geographic's upcoming six-part docuseries Hostile Planet, making him well-suited for today's activity.

After the show's crew spent 1,300 days filming for this series alone, Hugh-Jones has perfected his ability to spot the object of his search from a great distance. On this day's excursion, however, he didn't have to go any further than the harbor to witness a California gray whale pass below The Legend. It's a far cry from the seven days he once laid in wait for a polar bear sighting.

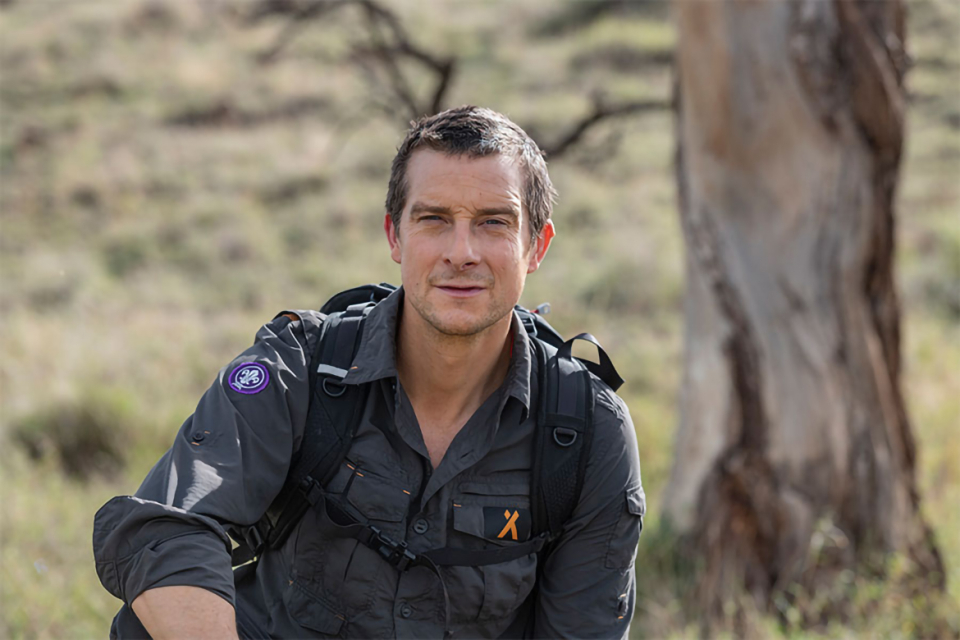

Hostile Planet, premiering April 1, traverses all seven continents and captures snow leopards, gelada monkeys, orcas, bull elephants, cheetahs and a pack of wolves, to name just a few highlights. In addition to Hugh-Jones, the series is executive produced by Bear Grylls—who also serves as host and narrator, Academy Award-winner Guillermo Navarro (Pan's Labyrinth), Martha Holmes and Delbert Shoopman.

Between whale sightings, Hugh-Jones spoke with emmy's Sarah Hirsch about Hostile Planet's potential viral moments, the moral dilemma of a documentarian and how he really feels about zoos.

Which animal have you not been able to capture on camera — your own "white whale" of sorts?

There was one we went after — fennec foxes — that I've always wanted to film in the wild. And we did film them actually, but we got very little footage, so I'd still love to do the ultimate fennec fox sequence.

It's super hard going because they're in the desert, and there are vast spaces you have to travel across in order to find them. And they're super shy, so as soon as they see you they disappear and change their den. But they're just so cute and lovable.

Have you had many instances where you were looking for one animal and you ended up coming across another?

In my career, the biggest one like that, is the snakes and iguanas sequence I filmed for Planet Earth II that went viral. We had no idea that there would be these huge groups of snakes chasing the iguanas. It was kind of luck. So yes, you often get something you're not expecting.

Have you had any moments like that on this series? Something that you think might go viral?

Yeah; we went to film snow leopards mating, and we ended up capturing this scene of a snow leopard catching an ibex, which is kind of unheard of. It not only catches it, it launches itself at the ibex, grabs it in mid-air, then falls maybe 200 feet, flips over, and somehow manages to keep hold of the ibex all the way down.

By the time it's at the bottom you think it must be dead. But it's alive, though really injured. We kept following it and about four days later it was back to hunting again.

There's another sequence in the "Polar" episode about gentoo penguins, which are actually doing quite well with climate change because they don't nest on the ice, they nest on the rocks. So there are so many of them now they're kind of taking over, and as a result, leopard seals have congregated in those areas to hunt them.

We filmed this epic chase where a seal catches a penguin, but because there's so much food for the seals it's kind of like, "Should I eat another cookie?" So it lets it go and the penguin escapes.

Are there moments when an animal's been harmed by a predator and you want to intercede, but can't?

Yeah, you never interfere by taking a prey animal away from a predator, because that's what they need to survive. But there are other situations... For example, when the camera team was filming barnacle goslings jumping off cliffs to go feed, one got stuck, so they went and helped it out of the rocks. Because otherwise it's just going to die.

Once I was filming with turtles, and they were getting confused by the lights of the city and instead of heading out to sea they were heading towards the city. And I thought, if I see one doing that, I'm going to pick it up and put it in the sea. You could argue that there's some sort of bacterial rat you're taking the food away from — it depends on how much of a purist you are.

We try not to interfere too much, but sometimes you've got to have a bit of heart.

What are your feelings about zoos?

I think the roles of zoos have really changed. At first they were a place of entertainment. It was an opportunity for people who couldn't travel to see the animals of the world. But there was a lot of pretty bad conditions that the animals were kept in.

Whereas now, zoos are playing an ever-more important role in forming community centers and institutions to breed animals and keep a genetic bank for some species that are really in trouble.

I actually helped Bristol Zoo re-establish a population of tree frogs. There were only a couple of places in Costa Rica — that were being deforested — where these frogs still existed.

So when we were filming them, we collected some, got a license to bring them back and they've now shared those frogs with zoos around the world. And they're a resource for a younger generation that isn't as connected with nature.

I don't love seeing animals kept in cages, but if it's going to help their species as a whole I think it's a necessary evil.

Have you ever found yourself in real danger while on a shoot — either from the natural elements or in the presence of an aggressive animal?

When we were filming the polar bears, it suddenly became really icy around our boat. The wind changed and all the ice started to crush up against the land and we got stuck. The ice could squeeze against you so much that the boat gets crushed and you sink. It was a frantic couple of hours where the captain was trying to break through the ice.

We got out, and he was very calm, but I hadn't appreciated how close it was. He said, "That was really, really dangerous, and we nearly died." But to me it seemed really exciting!

But the real truth is that most of the time the biggest dangers are when you return to the human world and you're in a car, or you're in a country with terrible crime. It's that kind of thing.

I only know of one sound man who died because of an animal — by an elephant. This was many years ago. But I know quite a few who have died in plane crashes, car crashes, that kind of thing. So yes, it's surprisingly safe out there. It looks treacherous, but we work with a lot of experts to try and convey the danger. But we're doing a lot to make sure it's safe.

Can you share some of the filming techniques you employed in this series?

I worked on a series called Life Story — which in some ways was like the inspiration for this show — where we really tried to film from the animal's perspective. In a lot of nature documentaries you use really long telephoto lenses, and they feel distancing. We wanted to film on the animal's level, following them with steady-cams and gimbals, to get some movement and make it feel more cinematic.

That was the first show where we really began to nail that approach. We tried to build on that with Hostile Planet. We did some experimental things like filming animals with racing drones. We wanted to make it feel like you are the animal and you're experiencing their world and what they do.

As exciting as that is, the series never feels like just a collection of cool sequences. There seems to be a narrative in each episode. How do those narratives develop? Are they mapped out before filming or do they reveal themselves as the filming happens?

A bit of both. It's not like a scripted series where you write out the script and go shoot it. But we work really hard to try and have characters that return throughout the show.

In most films and series you watch there is a sequence of events which affects all of the characters involved. So we try to apply that. In "Oceans" for example, we follow a journey out to sea, and we follow a storm back in. The viewer knows why they're going to the next show and then the stakes raise.

Which countries do you wish you had been able to visit for this series?

Unless you're working with a Chinese company, it's very hard to get access to China. There's not much wildlife there, but there are a couple of things that we would have been interested in doing.

In Niger, where they're doing research of Saharan animals, it's so remote the animals are almost naïve to humans, so you can get really close to those fennec foxes. And you see animals that are pretty much extinct to the rest of the Sahara. But it's really dangerous and we went through enormous trials to try and make it safe.

But as much as we wanted to film fennec foxes, it's not worth risking your life.

We went to most of the places we wanted to. You don't just turn up and hope you're going to find an animal. You're working with scientists and you're quite targeted about who you collaborate with and where you go. So there's some places that are really unexplored that I'd like to go to, but I'm going to have a really hard time filming wildlife there.

What's the longest you waited to capture an animal on film for this series?

When we were filming the polar bears, we went about seven days without seeing a single one. You're on a boat like this, it's freezing cold, and you're out every day, searching with binoculars trying to see a white animal on a white landscape, and you start to almost hallucinate. I became so determined that we caught up with them in the end.

What is the living situation like when you're out on location?

It really varies. Sometimes you'll be in a hotel, sometimes you'll be camping. Quite often you'll stay in a scientist's hut or something. So it depends.

We're so desperate to capture amazing moments, you're really putting all of your time and money into being out in the wild. You don't want to spend the money on hotels, you want to be able to afford a few more days when you get there.

I think my favorite is when you're literally dropped off in the middle of nowhere with a tent and a little stove and your camera kit, and the helicopter flies off and then you're there for three weeks with literally not a soul anywhere to be seen for five hundred miles in either direction…that's cool.