Anyone who knows me — or at least knows me well — knows that I love Columbo.

I've been writing a book about the series for over a decade, and once you get me started talking about the series, it's hard for me to stop.

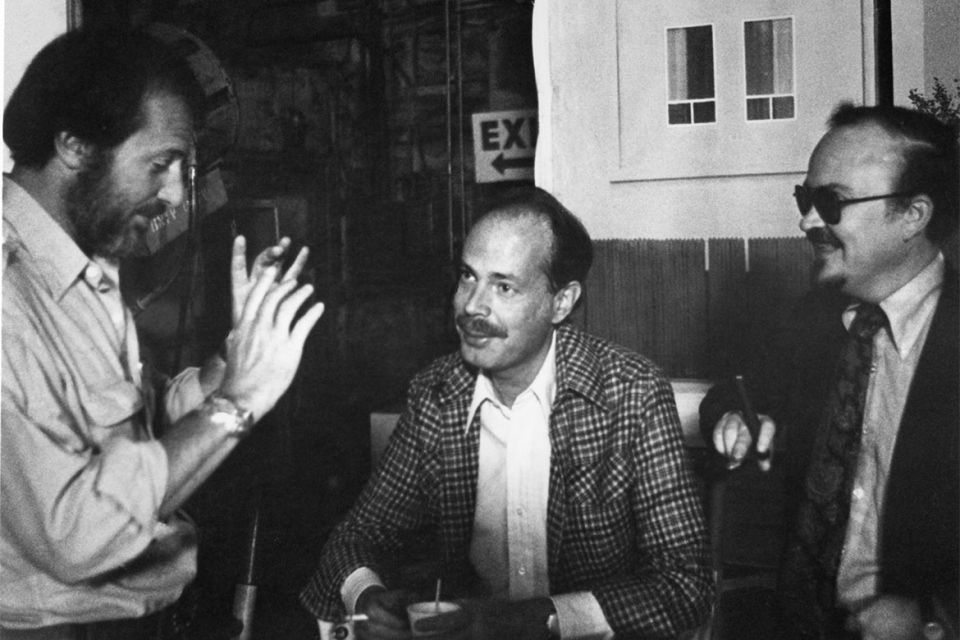

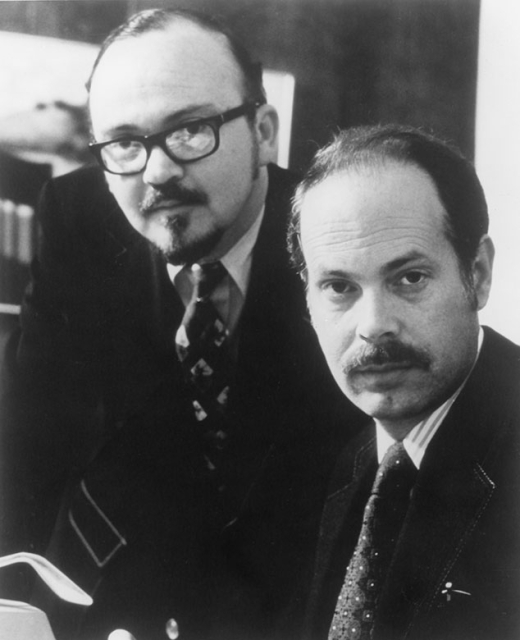

Those who have been paying attention to my long gushes about the series also know how much admiration I have for the co-creators, Richard Levinson and William Link, and how much affection I have had for Mr. Link who, until December 27, 2020 was the surviving member of the writing team.

In fact, it was a friend who texted me the news of his death, with a link to an obituary. As I followed the link, I felt my own breath leave my body in that moment, my chest contracting as a physical manifestation of both the loss of this good man and sympathy for his wife Margery Nelson. And, I admit, I also felt a great sense of disappointment in myself for not finishing my book earlier so that I could put a copy in his own hands.

After all, my work only got better as I got to know Mr. Link personally and as I came to know the extensive work that he and Mr. Levinson produced over their years together. I was terribly nervous the first time we spoke on the phone, but his warmth put me at ease. As our conversation came to an end, I asked if I might call him again.

"Sure," he said. "You seem like a very nice woman, and you know a lot about Columbo!" Overjoyed by this compliment, I hung up the phone, but I held on to this strange sense of familiarity. He reminded me of someone I knew, but who was it? And then, with the kind of flash that the most obvious of realizations bring, I knew who it was: he reminded me of Lt. Columbo himself.

Of course, he was much more than that. Through subsequent phone calls and visits to his home, I learned, for instance, that Mr. Link and I (like the eponymous detective) shared a love of dogs. And I learned that Levinson and Link were not just writers and producers but also magicians.

I soon after learned that in a feat less of magic and more of the compassion necessary to tell stories that were not their own that they were also dedicated humanists. UCLA Television Archivist Mark Quigley introduced me to their made-for-television movies, and he also made it possible for me to finally see the other series they co-created for the second NBC Mystery Movie line-up, Tenafly.

What follows, then, is a sketch of their work together that both led to and followed their most famous collaboration. I offer this sketch not just as a history lesson of sorts, but also as a tribute to the important work that Mr. Link and Mr. Levinson produced together and which, I believe, we can continue to learn from today.

Richard Levinson and William Link were plotting literary murders from the time they met in their Pennsylvania junior high school, and they continued to write together over the next four decades. Together they composed a high school musical, and at the University of Pennsylvania they co-wrote a television pilot as their undergraduate thesis.

After stints in the military, they reunited in New York City in the 1950s and started to work together professionally, penning short fiction and eventually becoming primarily writers for television. Their first broadcast co-creation was the episode "Face to Remember" of the Canadian anthology series Encounter (also known as General Motors Presents), which ran on January 18, 1959.

And they continued to write together for television for nearly 30 years, until the early death of Richard Levinson in 1987. "And I've missed him every day since," Mr. Link told me during one of our conversations over the years.

As the first iteration of Detective Columbo in the 1960 Enough Rope would show, detective writing was their primary modus operandi. Though evidence of that genre infects even those films that wouldn't be classified as such, in the television industry their long-running interest in mystery and crime was central to the series they worked on.

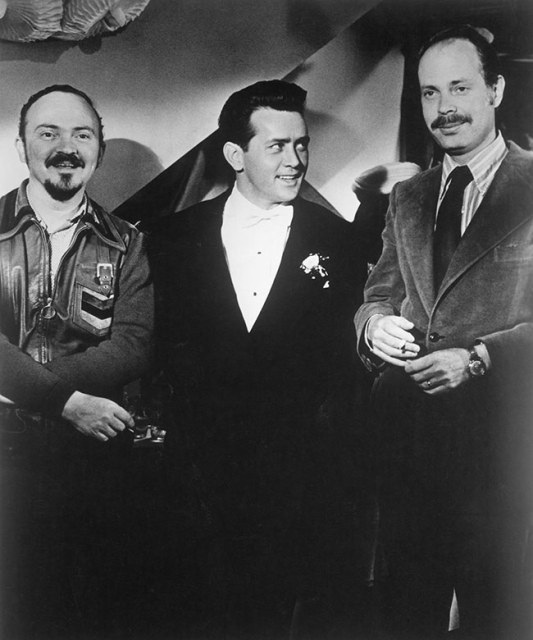

Extremely prolific writers, they contributed episodes to series such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, Honey West, and Burke's Law, and they created Mannix in 1967 with Bruce Geller. They subsequently wrote single episodes for two of the NBC Mystery series — McCloud and Banacek — and they also created Tenafly for the 1974-5 season of the Wednesday night edition of the mystery wheel series.

In the prime of Columbo, they adapted a new version of Ellery Queen, and in the years following they co-created with Peter S. Fischer both the popular series Murder, She Wrote and the short-lived Blacke's Magic. (After the death of Mr. Levinson, Mr. Link teamed up with David Black to create The Cosby Mysteries.)

After the first season of Columbo, Levinson and Link left the daily grind of the series. Though they continued to be involved through conversation with the new producers and with Falk — sometimes supplying clues, story ideas, or other elements — their break from the day-to-day of the series enabled the two collaborators to focus in particular on made-for-television movies.

Their major works of this time exhibited liberal (and sometimes more progressive) political concerns, making this otherwise mystery-writing team ahead of their time. Some of these elements are already part of Columbo. For instance, they designed rules of non-violence for the series (occasionally broken by others involved in the production), such as the fact that the detective did not carry a weapon.

This decision was in opposition to a series like Mannix, which took such a violent direction from what they intended that they never wrote for it themselves.

Moreover, as part of the signature formula of the series, every episode highlights class divides between the working class detective and the rich denizens of Los Angeles. Less obvious to a casual viewer might be the subject of race: on the heels of the Civil Rights era, Levinson and Link refused to intertwine criminality and race, such that none of the murderers on their signature series were Black.

Standing as a noteworthy companion to the weapon-less detective is the 1974 made-for-television movie The Gun. As the title suggests, the film is explicitly the story of a single gun and its effects on its owners over a three-year period. With this weapon as the titular character, the film opens with its "birth" of sorts.

From here on, the movie is made up of several vignettes which follow the same pattern: the date is announced on screen, the cost of the gun is declared (including when it's "free"), a new person takes ownership, danger appears to be imminent, danger is averted, and the story starts over again.

The final chapter reveals the attempted roundup of guns in the city, yet the original "character" goes astray, only to be snatched up by a worker. The film ends with the worker's child discovering the gun: the sound of its firing echoes while his mother washes dishes in the kitchen.

Hardly a mystery, The Gun still offers an investigation akin to that of a detective series, and its findings reveal the social and economic conditions that trigger personal crises across economic and racial lines.

Such inquiries were evident not purely of a non-violent ethos (after all, the writing team was regularly plotting murders for the screen) but of a humanistic sensibility that undergirded everything they originated together. This liberal humanism was spelled out most explicitly across three of their other made-for-television movies of the 1970s: My Sweet Charlie (produced in 1969, aired January 1970), That Certain Summer (1972) and The Execution of Private Slovik (1974).

None of them fit squarely into the detective genre by a long shot, but they offer investigations of complicated topics and stories for their time period — the aftermath of the Civil Rights era, the Stonewall riots, and the end of the Vietnam War.

My Sweet Charlie explores racism and an interracial romance; That Certain Summer concerns a 14-year-old boy who comes to realize his divorced father is gay; and The Execution of Private Slovik narrates the true story of the first US soldier to be executed for desertion since the Civil War.

None of these films offer easy solutions. Like the eponymous detective of Columbo, they are introspective. Offering the first positive representation of a gay male couple on television, That Certain Summer lays out some of the very concerns that will continue to characterize the LGBTQ movement for decades.

As the movie nears its end, father Doug and son Nick have a heart-to-heart talk.

Doug describes his relationship with his partner: "Gary and I have a kind of a marriage." When Nick insists that he doesn't want to talk about it, Doug gently presses on, "We love each other.... Does that change me so much? I'm still your father! I've lied to myself for a long time. Why should I lie to you? I should have talked about this to my own father... The hardest time I've ever had was accepting it myself. Can you at least try to understand it?"

Levinson and Link similarly personalize the dilemma at the heart of The Execution of Private Slovik, as the film queries who was responsible for the soldier's death. Its exploration of this central question begins with the soldiers who are commanded to kill him. Their Sergeant specifically asks: "Is there much talk about this among the men? ... How do they feel about it?"

And shortly thereafter the chaplain gives the "boys" who are charged with shooting Slovik the chance to talk about how they feel. Such questions concerning both the ramifications of the command to kill another soldier and the emotions involved in this act set the stage for the viewer's response to the events as well.

Through a structure that resembles the classic Citizen Kane, Private Slovik ultimately suggests that the accountability for Eddie's death is a shared one.

And then there's the short-lived series Tenafly. As the pilot premiered February 12, 1973, it was the first television drama with a male black actor/character in the singular (and eponymous) lead. Moreover, it was one of the only series during this era to include a Black writer, Booker Bradshaw, at the helm of two episodes, a demand which Levinson and Link negotiated when they made their deal with NBC.

As Herb Tenafly, James McEachin played a former cop who shifted to work as a detective for an insurance agency, and each episode balances an investigative case with a personal issue. Thus, while both the detective's actual family and overt mentions of race are absent from Columbo, in Tenafly each is woven into the narrative of every episode of the series.

Moreover, as was an element of the very plan of the series by Levinson and Link — a departure from Columbo — parts of each episode also take place at Herb Tenafly's home.

Certainly the series is an imagining of the lasting presence of African-American life in Los Angeles that Columbo — and almost every other drama on television in this era — does not reveal. On Tenafly, we see what Columbo doesn't see in the midst of his usual cases, and we go where his criminals don't normally take him: into the larger space of Los Angeles and into the middle-class homes of Black families.

Looking at Tenafly 40 years later, much like my experience of seeing That Certain Summer four decades after it first ran, produces for me an almost ineffable sensation, but surely one that is defined by an emotional one: the thrill of looking at a screen that holds only Black Americans together at home.

In this way, Tenafly enables a sense of intimacy with its characters that is otherwise largely unrepresented on television.

I realize now that I watch these various television creations as Lt. Columbo himself might have. Or perhaps it's more accurate to say that I have watched them as Columbo trained me to. That is, I see them as Levinson and Link have taught me to see, for this television duo helped to cultivate patient and even compassionate viewers.

As I write about their work in turn, I feel a profound sense of gratitude for what Richard Levinson and William Link gave to television viewers. And, given the ways that his kindness and his work profoundly shaped my own, I am particularly grateful for knowing Mr. Link.

Richard Levinson and William Link were inducted into the Television Academy Hall of Fame in 1995.