William Shatner's decades-long relationship with fame began on the theatrical stage as a young Canadian actor before American television helped turn him into one of the medium's most noteworthy stars.

With roles like the traumatized airline passenger aboard the classic Twilight Zone episode, "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet," and, of course, his most famous part — Star Trek's Captain James T. Kirk — Shatner would spend more than five decades becoming a load-bearing column of pop culture. His landmark career, with all its considerable peaks (winning two Emmys for his role as attorney Denny Crane on The Practice and Boston Legal) and valleys (the cancellation of Star Trek), is the subject of his latest documentary, You Can Call Me Bill. The doc, directed by Alexandre O. Phillippe, weaves key moments and events from Shatner's life and profession with the 93-year-old actor's preoccupation with his own mortality — which seems sparked by his recent trip into space at the age of 90 on Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin rocket.

In the documentary, a vulnerable Shatner reflects on his talents by saying: "Every human being is limited by who they are." If his industrious career is any indication, he seems to be the exception to the very limits he speaks of. With the pending release of You Can Call Me Bill on VOD April 26, Shatner spoke with the Television Academy and reflected on some of his most memorable TV roles and experiences.

Television Academy: I know it's been a long, long time, but how was your experience working with the late director Richard Donner on The Twilight Zone episode, "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet?"

William Shatner: I had come from live television out of New York and Donner was a very prolific director. I had worked with him several times prior in live television. So we were more or less friends, pretty good acquaintances. So when he called, it was like an old buddy saying, "Let's do this thing." And when I read it — I was of two minds. I mean, it could be laughed at. And then when I saw the suit that the Czechoslovakian acrobat was dressed in, I thought, "Well, I hope this isn't laughed at." This is good for laughs, at least.

The last thing we shot was the last shot of the episode, where my character is being carried away on the stretcher. And [while shooting], I remember thinking: "I hope that everybody takes this thing the way it was meant to be [taken] and not laugh at it." Since we're talking about it more than 60 years later, my hope seems to have come true.

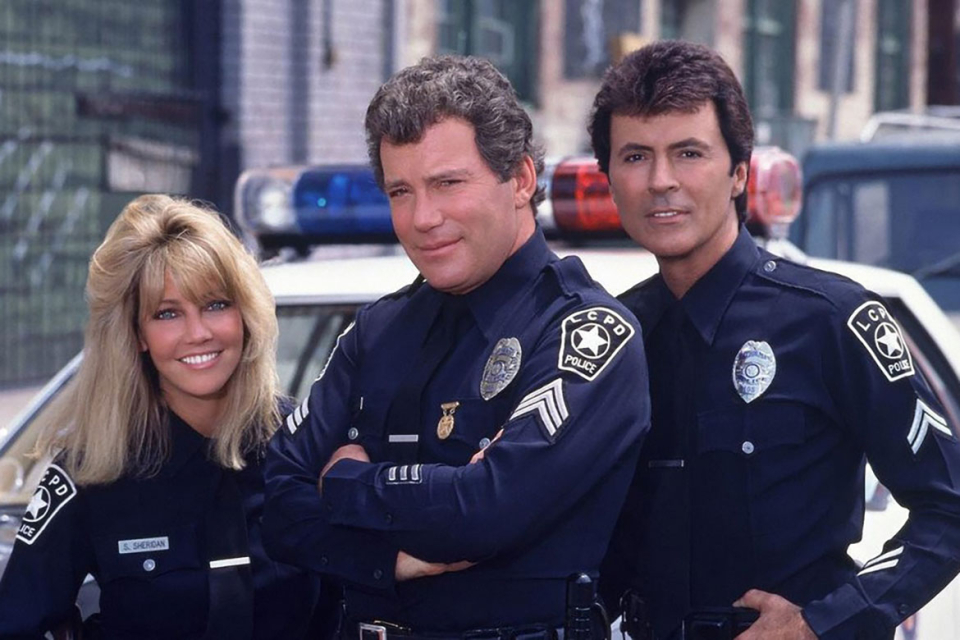

Moving on to T.J. Hooker, 1982 was a significant year for your career — with this series airing March 1982, ahead of the June premiere of the feature film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. How did the role of Hooker, which was a significant departure for you at the time, come about?

Well, before the exigencies of television got ahold of it, it was meant to be about a cop who hadn't progressed into the modern police age. So, the complex idea for T.J. Hooker was this cop trying to work himself into the modern age. At its best, the show did that. And, at its worst, it was a good cop show.

The series went from ABC to CBS for its fourth season. Can you recall why that change happened and how that impacted you?

I wasn't aware. I just knew it was happening, to the best of my recollection. As long as it went on the air — on somebody's air — I was happy.

And T.J. Hooker afforded you opportunities to direct, as well. How was directing television different — or maybe more exciting for you — than, say, directing feature films, like your feature directorial debut, 1989's Star Trek V: The Final Frontier?

Well, in television directing, the common knowledge is you're good for [getting] one artistic shot a day. Meaning a director gets that shot and you're busy doing close-ups for the rest of the day — just getting in and getting out. So I would try to take advantage of that time to set up a good shot — whether the camera was moving, or whether it was an artistic shot where I'd want the lighting a certain way. It all took time, and I had to ration the importance of [getting] that shot that I would have thought of that morning or the night before. And I would fight to get it in, and then stick to getting fairly close shots from then on in the interest of time. So, when I got to direct a feature, I was armed with the knowledge of how to save time while filming.