When Kenya Barris was pitching his show Black-ish, a sitcom about an upper-middle-class African-American family, he told network executives, “Let’s do Norman Lear today.”

The show premiered this season on ABC, whose entertainment president Paul Lee had told Barris, “You have to do it honestly, unapologetically.”

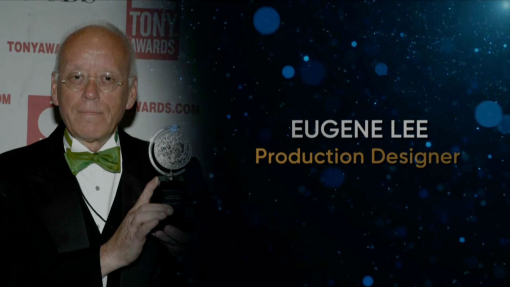

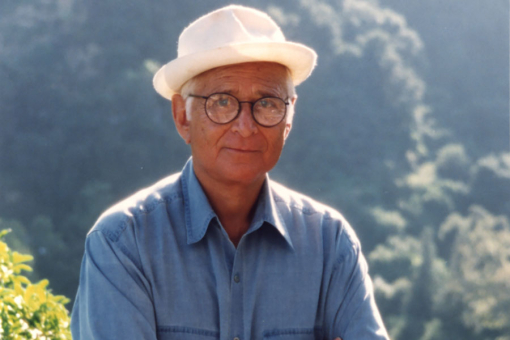

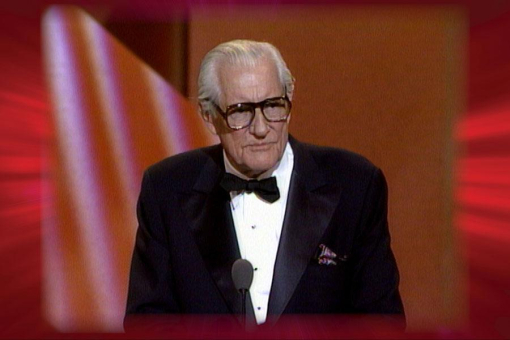

Being honest and unapologetic would certainly describe Lear’s shows, among them All in the Family, The Jeffersons, Maude, Good Times, Sanford and Son and One Day at a Time. Barris was one of a number of guests paying tribute to the prolific creator-producer-writer-director at the Television Academy’s first members’ event of the year, “An Evening with Norman Lear.”

Held January 28 at the Montalban Theatre in Hollywood, the event explored how the four-time Emmy winner’s shows, several of which spotlighted black characters and families in positive ways not previously seen on television, paved the way for the development and popularity of urban contemporary music, such as hip-hop. Guests also shared how Lear’s shows had influenced them personally and professionally.

Besides Barris, those joining Lear included rapper-actor Common; rapper-photographer D-Nice; Def Jam Records co-founder Russell Simmons; Steve Stoute, author of the book The Tanning of America; Baratunde Thurston, comedian and author of the book How to Be Black and in surprise appearances, Marla Gibbs of The Jeffersons and non-Lear show 227, and Regina King, who played Gibbs’ daughter on 227. Music journalist-cultural critic Toure, a co-host of MSNBC’s The Cycle, moderated.

Lear, who is now 92 and the author of the new memoir Even This I Get to Experience, said he tackled serious issues within his shows’ comedy because “I’m a serious guy. My father went to prison when I was nine years old. I was alone for several years, living with this uncle, that uncle. It was not an easy time. But I saw the foolishness in the human condition. … I take life seriously, and I find humor in everything.”

The humor and the truth of Good Times (1974-79) resonated with first guest Common, a Chicago native; the Maude spin-off which Lear developed was about a family in Chicago’s inner city housing projects. “Every person of color didn’t grow up poor, but we really related to the family dynamics, the things they went through,” he said. “We got to see a lot of truth about the family and relationships within the family. It was great to see ourselves on television in a fun way.”

Esther Rolle and John Amos starred as Florida and James Evans; though Lear said he realized they bore the heavy responsibility of reflecting American black family life to black viewers, many issues raised, such as a teenager talking to her mother about sex, were universal to all families.

Maude had been a spin-off of Lear’s first groundbreaking show, All in the Family (1971-79). He never considered lead character Archie Bunker (Carroll O’Connor) to be a racist, he said. “I saw him as fearful of progress. He wasn’t a hater. He was fearful: Black people are moving in next door; what’s going to happen to me?”

Those neighbors went on to have their own spin-off, The Jeffersons (1975-85), about well-to-do black couple George and Louise Jefferson (Sherman Hemsley and Isabel Sanford). Toure drew parallels between George and hip-hop. “George had the swagger, the wit, the entrepreneurialism, the rejection of the white gaze – that became what hip-hop is all about.”

Agreed Common, “Hip-hop is about coming out of the inner city, not having much and turning that into something. The whole ‘Movin’ On Up’ thing [The Jeffersons’ theme song] – not only would I look at it as literal, but figuratively – moving up to a higher place. That’s the basis of hip-hop, really.”

Many artists have rapped to that and theme songs from other Lear series, he added. “[They] are ingrained on us, and they have a universal appeal.” And he believes all of Lear’s shows influenced the artists, as the episodes were discussed at school and influenced how the young viewers grew up, which was later reflected in their music.

Russell Simmons definitely identified with George Jefferson. “[He] was my man. I walked like him – he had that swagger, plus, his success made me inspired,” he said. “He was a successful black man, and he didn’t bite his tongue. It was a road map: Be yourself.”

As for Barris, he called his approach to Black-ish “derivative. It’s based on my life and my family, but it was completely looking at what Norman had done. He took honest stories, and he told stories other people wouldn’t tell. To tell comedy with a point behind it, on subjects, issues, is almost impossible. … You were doing it at a time when America was not accepting of it.”

Barris was concerned that viewers would not like a Black-ish episode about the issue of spanking – and not spanking – kids, but they accepted it. “It’s all because of what you did, and the road you paved for me,” he told Lear. “Thank you so much.” He also learned from Lear that “you build a character, establish him with layers, flaws, idiosyncrasies. Once you do that, you can put a character in any situation, and you have a story.”

Lear said that his own stories came from the authenticity of his life, his family members’ lives, the lives of his writers and their families and from sources such as newspaper articles. “For some reason, on the shows that preceded ours, ‘The roast is ruined and the boss is coming to dinner’ was a big problem. Yes, you can have some fun with that, but you can also have fun with things going on in the family.”

The event was a presentation of the Academy’s activities committee, co-chaired by Tony Carey and Michael Levine.

Watch the replay of the entertaining two-hour event.