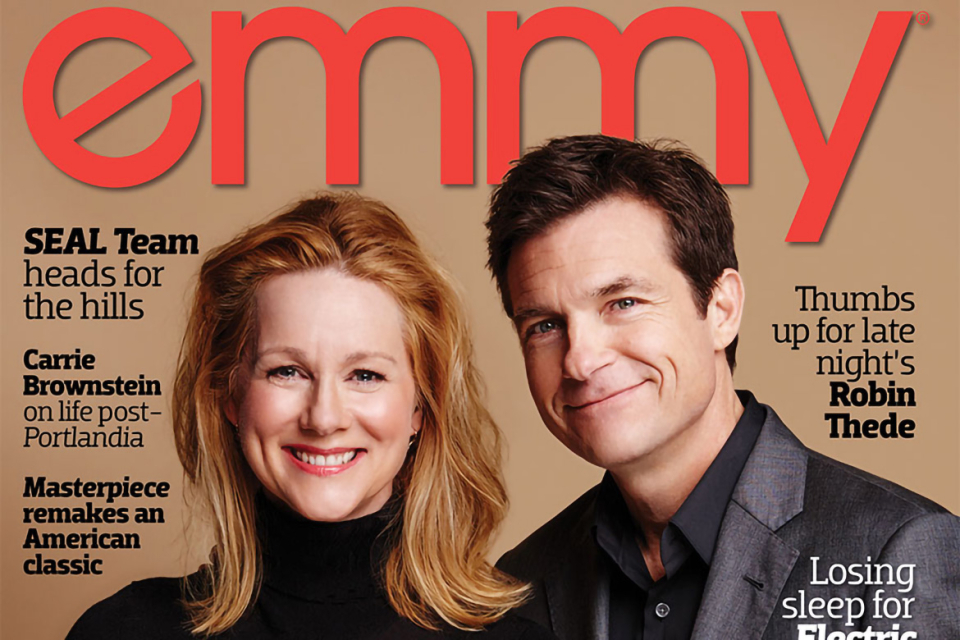

Beyond the string quartet and the ice sculpture, through a crowd of cheery black-tie guests, Jason Bateman and Laura Linney are dancing cheek-to-cheek, whispering conspiratorially.

As Marty and Wendy Byrde, the duplicitous, money-laundering duo on Netflix's crime drama Ozark, they sway and smile in the ballroom of Atlanta's stately Georgian Terrace hotel, plotting their next con. It's an unusually elegant setting for a series so unrelentingly dark. But, as fans discovered in the dynamite first season, nothing is as it seems in this show.

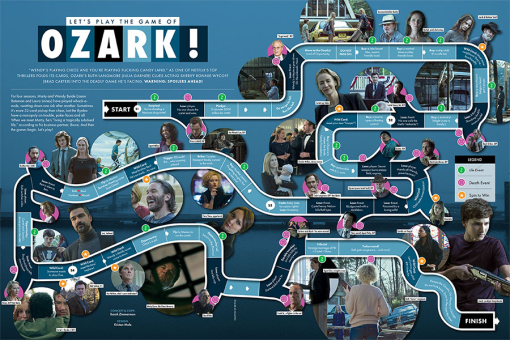

And in the second season, due this fall, the stakes are even higher. Over the course of 10 episodes released last July, the Byrdes run for their lives from suburban Chicago to the Lake of the Ozarks in Missouri with their two teenagers in tow — and a deadly Mexican drug cartel on their heels.

In no time, bodies turn up in the lake, a preacher's pregnant wife disappears, hit men are parked outside and the Byrdes' son develops a fondness for dead animals and shotguns. Yet, somehow, there's still time for mundane marital squabbles over parenting choices and overblown adolescent drama.

"The Byrdes are a family just like many others — another family with money problems," says Cindy Holland, Netflix's vice-president of original content. "I think what's captivating to audiences is, you keep asking yourself if you were that character, what would you do? It starts from a point of real relatability and just keeps spiraling from there."

That gangbusters narrative earned Ozark a second-season order just three weeks after its debut. By fall, Bateman had earned an acting nomination from the Golden Globes, he and costar Linney each had nods from the Screen Actors Guild Awards and the show had a nomination from the Writers Guild. By December, cast and crew were headed back to Atlanta for another six-month shoot.

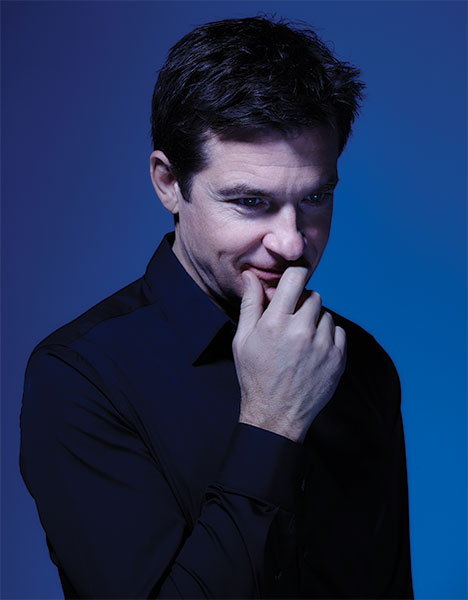

On this chilly winter day, there's a palpable sense of camaraderie among the crew, a mix of locals and L.A. interlopers. Bateman is not only a series star, but also an executive producer and director, and his poised professionalism clearly sets the tone.

After a few takes in the ballroom, he darts out to watch playback on a monitor with cinematographer Ben Kutchins. Adjusting his tux as he perches on the edge of his director's chair, Bateman offers quick, precise notes, requesting a different lens to shoot that ice sculpture and a tighter shot for the partygoers.

In minutes, he's back on set, consulting crew on lighting. "The thing about Jason is, he gets straight to the point," Ozark cast member Julia Garner says in a call from New York. "There's no running around in circles with him. A lot of people make you run around. And Jason doesn't do that. He knows what he wants."

Ozark presented a unique opportunity for Bateman. As an actor, the role offered a complex setting for the sardonic everyman character he'd mastered during his three seasons as Michael Bluth on the Fox cult comedy Arrested Development. As an executive producer — a credit he shares with showrunner Chris Mundy, creator Bill Dubuque and Mark Williams — Bateman wanted to treat the 10-episode series as "a 600-page movie."

"From a visual sense, I thought it was important to create an environment, an atmosphere, a tone, a palette that felt kind of raw and authentic and a little frayed," he says while waiting for crew to reset the scene. "It's not tidy. Bad things could happen here. It's real. Colors are probably desaturated and lenses are a little bit longer.

"The music is a little bit more atmospheric and sonic than it is rhythmic and melodic. All things in each department contribute just a little bit to create an unsettling world."

In the first season, as the Byrdes' marriage is collapsing over Wendy's infidelity, they discover that, to stay alive, they have three months to launder $8 million in an insular rural Missouri vacation spot. They frantically buy up every tourist trap they can find on the lake while playing it straight for their two adolescent kids. Meanwhile, two local criminal clans threaten it all with their own deadly schemes.

Even the writers thought the first season would be hard to top.

"We wanted to make sure that, despite the fact that there were these insane things happening and this crazy premise, at every point we were trying to ground it in reality," says Chris Mundy, who is also head writer. "This year, there's something we might have Marty and Wendy do that — although it seems small in comparison to some of the other crazy things — we're arguing over whether people would forgive them."

In season two, the Byrdes dig their hole even deeper. Now they have $50 million in drug money to launder and at least that much in heroin to move.

In the Georgian Terrace scene, they're crashing a Kansas City fundraiser to befriend a political kingmaker in hopes of launching a legal waterfront casino. "It's a bit like a Chinese puzzle," Linney says, pausing at one of the ballroom tables. "They've reached one level of safety, and a whole other level of danger opens up to them."

Ozark quickly drew comparisons to AMC's legendary crime drama Breaking Bad, with Bateman's family- man financial adviser likened to Bryan Cranston's high school chemistry teacher. But Bateman, a fan of David Fincher and Paul Thomas Anderson, had a few other influences in mind when he envisioned his show. Above all, he aimed to have "a fine touch" that would avoid anything treacly or overly earnest.

Having grown up in the business — from a child star into a leading man whose tinder-dry wit and masterful comic timing earned him two Emmy nominations for Arrested Development — Bateman knew what he was doing.

When the Ozark script reached him, he'd recently directed and produced two dark comedies. In 2013's Bad Words, he plays an obscenity-spewing 40-year-old who competes in children's spelling bees. In 2015's The Family Fang, he and Nicole Kidman star as siblings traumatized by their parents' macabre performance art.

He wasn't looking for a TV series, but once he'd read creator Bill Dubuque's script, Bateman wanted to run the show. He pitched an unconventional structure to Modi Wiczyk, co–CEO of Media Rights Capital, the production company behind the series: Bateman would direct four episodes and serve as a film-style director, overseeing everything but the script.

Mundy, known for his work on Bloodline and as showrunner of AMC's 2013 thriller Low Winter Sun, would plot the narrative and run the writers' room from Los Angeles.

"He has autonomy over his lane — all the scripts, all the writing, the plot: who should we kill? Who should we not?" Bateman says. "And I basically cover everything else. The shooting. Hiring of other directors [Daniel Sackheim, Andrew Bernstein and Ellen Kuras also directed season-one episodes]. The casting. The performances. A large portion of the editing. We're still kind of figuring it out as we go forward."

Bateman asked the production design team to study the aesthetic of cinematographer Adam Arkapaw, who won Emmys for his work on HBO's True Detective and Jane Campion's BBC–SundanceTV series Top of the Lake. Bateman also referenced writer-director Scott Cooper's 2013 steeltown thriller Out of the Furnace.

Before the start of shooting, Bateman hired composers Danny Bensi and Saunder Jurriaans, who had scored his 2015 thriller The Gift. For Ozark, they created a standout sound palette of distortion and "junk percussion."

The Ozark cast, meanwhile, features a mix of young and established talent. Most of them come with acclaimed stage and film experience and aim for realism in their portrayals. As a director, Bateman says he gives them the space to evolve their characters independent of his influence.

"I feel that the part is the actor's to play," he says. "It's not the director's to kind of shove the actor into. It's not the writers' or the studio's or the network's. As long as there's an agreed-upon finish line, it's the actor's prerogative to get the character there any way they see fit."

Scottish character actor Peter Mullan (Top of the Lake) plays the genteel and deadly heroin manufacturer Jacob Snell. Jason Butler Harner (Ray Donovan, The Blacklist) gives a visceral performance as an obsessed undercover FBI agent. Michael Mosley, a versatile actor with lengthy film and TV credits, was so compelling as the lakeside preacher whose life is upended by the Byrdes that Netflix cast him in the drama Seven Seconds, which premiered in February.

But Julia Garner stands apart as Ruth Langmore, a criminal genius and the teenage matriarch of a clan of impoverished ne'er-do-wells. She's made an uneasy alliance with Marty, running his strip club while plotting his murder. In season two, she faces a reckoning when her steely ex-con father gets paroled.

"You're not watching somebody perform — you're actually witnessing an actor frame up a part of themselves," Bateman says of Garner.

Garner first earned critical note with roles in the 2011 Sundance hit Martha Marcy May Marlene and more recently on Netflix's 1970s drama The Get Down. She splits time between the Atlanta set of Ozark and the New York set of FX's Emmy-winning The Americans, where she plays the daughter of a CIA agent.

Garner describes herself as "a Jewish girl from the Upper West Side." But in Ruth, she embodies a Southern firecracker as at ease rigging a deadly booby trap as she is firing a gun. Though, she admits, the first time she had to fire a gun as Ruth, she screamed.

"I knew that Ruth was going to be a three-dimensional character," Garner says. "There wasn't one character in the show that wasn't developed. Each character had its own subconscious."

Show creator Dubuque grew up around folks like Ruth and the Langmore clan. As a teen, he spent summers at the Lake of the Ozarks, working as a handyman, pumping gas and manning the grill at the Alhonna Resort, the inspiration for the series' Blue Cat Lodge. After he had a family of his own, they vacationed at the lake.

"When I talk to people who are not familiar with Missouri or the Midwest, they think I'm making it up," he says in a recent call from his St. Louis home. "I can show you a home for $5 million, and I can show you a home that's worth $30,000, and I can show you abject poverty. I can take you on the outskirts of town to a trailer with two horses in the front yard and two Confederate flags. It's this whole mix of everything."

While researching his 2016 Ben Affleck thriller The Accountant, Dubuque learned a lot about money laundering. He started playing with the idea of a family man saddled with loads of illegal cash and how that conflict might play out in the Ozarks. In the process, the show illustrates the class divide in America that has come to define the most polarized political climate in generations.

"I thought if I could do those things and use the lake as a metaphor for capitalism and power, I'd have a winner," Dubuque says. "Then it was getting into these characters without making them look like stereotypes." In the writers' room, Mundy says, early discussions revolved around how HBO's The Sopranos juxtaposed horrific crimes and unrelenting danger against the ordinary challenges of a privileged middle-aged couple raising two adolescents.

"We really thought about it as a story about a family in the middle of this," Mundy says. "The arc of the first season was about this marriage: can it survive? And this family: can it survive? More than this plot about [whether they can] launder this $8 million. You just felt in this strange way that if any viewer was thrown into this situation, this felt realistic."

Throughout the series, scenes of ordinary stress are mixed in with life-changing devastation and terror. In the pilot, Bateman's Marty blithely talks a young couple through some financial planning options, while surreptitiously watching a surveillance video on his computer of his wife unbuttoning another man's pants. There's no indication from his even tone that it's the first time he's confirming her affair.

After movers unload all their belongings onto the front lawn, Marty chides his kids about bringing in some boxes, while pausing to matter-of-factly explain the meaning of money laundering . Later, Marty's son secretly watches a gruesome news report about the murderous cartel that employs his father.

Wendy, desperate to normalize the situation with a grocery-store run, goes on a pilgrimage for her daughter's favorite pistachio ice cream, only to glimpse Mexican hit men tailing her. When a store clerk tells her they only have mint chocolate chip, she throws a tantrum right there in frozen foods.

"What's the most fun in dealing with her, even now, is that she's a woman who doesn't know herself very well," Linney says. "She's very capable, but she's not terribly mature. And she's not very in control of herself."

Linney, a three-time Oscar nominee and four-time Emmy winner, last led a TV series as a suburbanite grappling with cancer in Showtime's The Big C. After four award-winning seasons, the show ended in 2013.

When Bateman approached her, Linney had just finished two dramas, the 2015 film Mr. Holmes opposite Ian McKellen and the 2016 biopic Genius. He flew to New York and took her to breakfast to make his pitch. Bateman knew Linney's pedigree would draw talent to the production.

"She doesn't do a lot of acting," Bateman says. "Everything is just very real. So you have to make sure you've got your shit together. Everything needs to be buttoned up so you're as believable as she is, which then basically adds up to chemistry."

Together, Linney and Bateman cultivate a restrained sort of depth and intensity that not only amplify the tension of Ozark but also bring humanity to the show.

"When you sign on to something like this, you have to take into consideration it could last for a very short period of time, or it could last for several years," Linney says. "It's all about the people that make the material, and the material itself. I just followed an instinct. The world [of Ozark] itself is interesting. But really, I wanted to help Jason create something that was different for him."

Go behind the scenes of emmy's cover shoot with Jason Bateman and Laura Linney at TelevisionAcademy.com/cover.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 4, 2018