Silence was the killer.

It shrouded basic truths in secrecy, muted necessary questions and enabled fatal incompetence. Technically, the killer was radiation from Chernobyl, the worst nuclear disaster in history. But one of its deadliest weapons was secrecy.

Just how many were killed? The official Soviet death toll is 31. Some estimates exceed 1 million. Still, no one knows, even 33 years later.

Most people don't know a lot about Chernobyl, other than that it was a nuclear explosion that spread panic around the world.

That ignorance intrigued Craig Mazin, executive producer and writer of Chernobyl, a gripping five-week miniseries which premiered May 6 on HBO (also executive-producing are Carolyn Strauss and Jane Featherstone; produced by Sister Pictures and the Mighty Mint, Chernobyl is an HBO/Sky coproduction).

Five years ago, reading an article about a containment structure being built over Chernobyl, Mazin — who's known for writing lighthearted fare like The Hangover Parts II and III — realized, "I wanted to do a story about something you think you know, but really have no idea.

"The explosion is merely the beginning of the madness," he explains. "It's like quicksand. It just gets worse and worse. I always felt the most important stories I wanted to tell were the human stories. I wanted to express the truth of that night — the fear, denial, confusion and chaos."

Still, Mazin, a former neuropsychology major at Princeton, faced the challenge of making a complex subject comprehensible. Terms like enriched uranium and control rods make most people long for the relative wackiness of congressional hearings on the tax code.

And at first blush, an in-depth study of a nuclear disaster that happened in 1986 feels more like a PBS documentary than a subject for HBO, especially for a miniseries.

In fact, that was the initial reaction at the premium-cable network, according to Kary Antholis, president of HBO miniseries and Cinemax programming. Until Mazin began his pitch.

"Chernobyl will be a horror film," Antholis recalls Mazin saying as he laid out his vision. "It will be a war movie. It will be a political thriller. And it will be a courtroom drama. And you know, however bad you think Chernobyl was, it was hours away from being much, much worse — from devastating millions of lives and wreaking havoc on the European continent."

Director Johan Renck (Breaking Bad, The Walking Dead) was living in Stockholm during the disaster. He recalls, "It was a big deal and obviously back then, information was curated." As he read the script, he asked Mazin: "How much of this is real?"

All of it, Mazin said.

"I was a fiction believer and as a filmmaker, I came from a place that the truth is there to be bent and shaped to the cinematic experience," Renck says. "And then I became the most staunch advocate of the truth because, for me, the shift that I went through, everything has to be utterly true. You cannot bend the truth to our benefit, and the truth is much more interesting."

If you can find it.

The first person in the series who recognizes the magnitude of the catastrophe is nuclear scientist Valery Legasov, played with the right mix of horrified incredulity and logical determination by Jared Harris (Mad Men, The Crown). He understands how atomic energy works and suspects what has happened, while everyone else still thinks they're dealing with a mere fire.

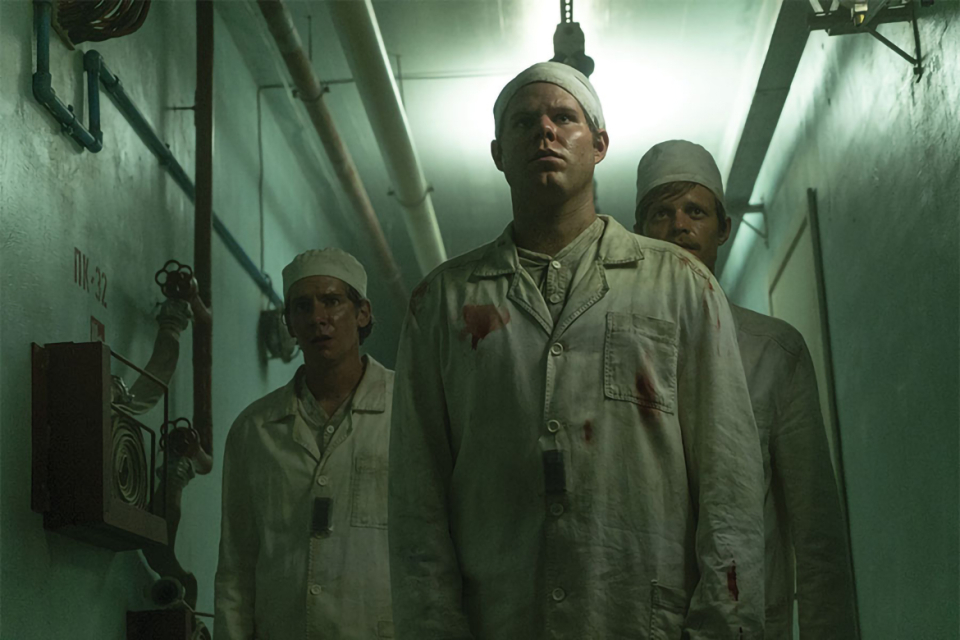

As sirens blare, first responders race to the power plant. An otherworldly glow enshrouds the remains of the reactor, from which spews a toxic cloud. Firefighters on the scene handle contaminated graphite. They can taste metal seeping into their mouths. Yet no one questions what's going on.

That's understandable. It's an emergency, and the fire has to be extinguished. Moreover, it's happening in Soviet Russia, where challenging authority is a death wish. No one dares to hesitate or even raise any doubts.

Meanwhile, the scope of the disaster is incomprehensible to almost everyone. Parents bring their kids out to watch the fire as radioactive ash flutters down. Their innocence adds to our tension: unlike them, we know what's happening, and how devastating a massive nuclear accident is.

In addition to being the first to recognize the gravity of the accident, Legasov is the first person the viewer encounters. We have no idea who he is, but clearly, he's a man on a final mission: scribbling notes, dictating into a tape recorder, determined to set the record straight.

In the end, the Communist Party's willingness to deceive, and to scapegoat its own woefully unprepared workers, was too much for Legasov. He committed suicide on the second anniversary of the disaster, although like everyone else at Ground Zero, he would likely have died prematurely.

Harris, who was a drama student in London in April 1986, says he remembers "vividly the cloud heading our way. The warning to not go outside became dire when it rained."

Though he's fond of researching characters, Harris says, "Craig needed something else. It was one of the few times I played a real character, and I didn't find research to be particularly helpful."

For Harris, it's the relationship between his contained, studious scientist and Stellan Skarsgård's Boris Shcherbina, a volatile career Party man, that defines the character. "They needed contrast," he says.

The men are naturally wary of each other — a sheltered academic, programmed to question facts, and a brute fighter, conditioned to accept orders — but they soon realize they must trust each other, and a mutual respect flourishes.

Legasov is summoned to meetings, where he explains, "The fire we are watching with our own eyes is giving off nearly twice the radiation of the bomb at Hiroshima — and that's every single hour, hour after hour." Trying to impress officials with the gravity of the situation, yet holding onto a scientist's calm detachment, he predicts, "It will spread its poison until the entire continent is dead."

Death is already cutting a wide swath through northern Ukraine. Though the series isn't gratuitous about the hideous effects of radiation poisoning, it includes scenes of projectile vomiting, blistering skin and liquefying organs. Miners, soldiers and first responders work continuously to collect radiated debris, shut off valves and try to contain the disaster.

Within 36 hours, the area is evacuated. Today, the once-thriving city of Pripyat remains a ghost town. Reactor No. 4, where the explosion occurred, is encased in a new container. But during those first days, when the disaster unfolded, it was still a mass of steel bent into grotesque shapes, belching radioactive waste.

Depicting that horrifying landscape required a very specific sort of set design. Part of the hundred-day shoot took place in Lithuania, both on a massive stage and in a real nuclear power plant. Offices in Kiev were used for interiors and exteriors, while buildings in Moscow helped establish shots.

"What that gave us was scale on the ground," production designer Luke Hull says. "We took this stage, a studio in Lithuania that was never finished — a husk of a building. It offered a good set for the shape of the reactor and also the landscape beyond."

The set itself, he says, was huge, filling the equivalent of 10 football fields. Recreating the real disaster, the smoldering remains had to be entombed. Several scenes focus on the heaviness of the gray concrete being poured over the building and over the coffins of those who succumbed early.

"It was a lot of concrete," Hull says. "Smoke-wise, special effects pumped a lot of smoke through that would be colored in after." As impressive as these sets are, sometimes the real backgrounds jump out, such as a bare-bones Soviet lab from the 1980s, where we first meet nuclear physicist Ulana Khomyuk, a composite character played by Emily Watson.

An unapologetic realist, Khomyuk quickly surmises the vast scope of this disaster. She charges into meetings uninvited and takes on even Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, in itself a shocking stance.

"For me, my most important piece of research was at the Tate Modern," Watson says. The actress had gone to the museum to take in a Modigliani exhibit, but a retrospective of Soviet-born artist Ilya Kabakov's work struck her deeply. Titled "Not Everyone Will Be Taken Into the Future," it showed the vastness of what would be lost if people left art behind. In that bleakness, Watson found Khomyuk's courage.

Assembling a timeline, Khomyuk tries to determine precisely what has happened and why. If she can pinpoint the disaster's causes, she reasons, she might be able to prevent similar catastrophes at the Soviet Union's 16 other reactors — which all have the same flawed design as Chernobyl.

In one scene, she tries to push her way into a meeting with an aggressively stupid, mid-level party apparatchik as his secretary tries to detain her.

What could be a nothing moment instead becomes emblematic of this miniseries' careful aesthetic. The blowhard's secretary wears a polyester dress that may have a longer half-life than enriched plutonium. Her turquoise eye shadow and dyed coppery hair make her a vision of mid-'80s Eastern Bloc fashion.

"The Soviet Union was completely isolated at the time," costume designer Odile Dicks-Mireaux notes. "It was so different than what was going on in the '80s in Europe. It did have its own look."

She relied on costume houses in Belarus, Ukraine, Lithuania and the Czech Republic to outfit the cast with clothes that bore the CCCP (USSR) label. "In Lithuania, we had a tailor who trained in the early '80s, and she managed to source wool and polyester suiting that is hard to get now," Dicks-Mireaux says. Local markets were a source for period-authentic eyeglasses.

For such an inherently dramatic story, the series begins leisurely, establishing a tone of peaceful prosperity in nearby Pripyat. At 1:23 a.m. on April 26, 1986, a firefighter and his pregnant wife watch the sky brighten over the plant. Naturally, he races to the fire.

Initially, she isn't too worried — he's fought fires before. Ultimately, she would be among those who paid dearly. Her husband dies, and her baby is born with fatal defects.

But it takes a while for the authorities to admit what he has encountered. Over the course of the five episodes, 104 speaking roles cover the genres Mazin had promised HBO in that pitch meeting. Firefighters, miners and the military work relentlessly to put out the fire and contain the disaster. The tension escalates long after the initial explosion.

"For me, it is a war story," director Renck says. "It has the same sort of fear and horror. But everything changes so much in the coming episodes — there is always a new mood we have to embrace and follow through."

Even though we know, ultimately, what happened — a flaw in the design that was supposed to help cool the reactor heated it up instead, triggering the explosion — the series returns us to those days when no one knew the truth.

This sort of catastrophe, classified as a Level 7 major accident, had never happened before; 1979's Three Mile Island meltdown in Pennsylvania was a Level 5 accident with wider consequences, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency's Nuclear Event Scale.

As Legasov realized what was happening and tried to persuade Soviet officials to act, he ran into an immutable wall of silence. Harris says he finds that part of the story sadly familiar. "I see similar things happening now with the suppression of the truth," Harris observes, "[like] the successful effort to silence the debate with climate science.

"Our story is an entertainment, but it's also about how dangerous it is to suppress the truth. They didn't have the mechanisms to speak truth to power, and quite often the people who pay the price are regular people."

Thousands of nameless firefighters, miners and military members sacrificed themselves for the greater good. These unsung heroes haunt.

"The most important takeaway has to do with the human sacrifice," Renck says. "This is a film that to some extent, even while vilifying the Soviet system, still casts the Soviet people as heroes."

Firefighters and soldiers wore uniforms, but some warriors wore boxy dresses as they took on the powers working to suppress the truth.

"It took incredible heroism to stop it," Watson says of the scientists who spoke up. "It lays bare the relationship of speaking truth to power. And controlling information about climate change is a very similar situation.

"We owe it to ourselves to have a standard of information for truth. The relationship of truth shows us the balance of power with politics and science and protection of the planet. It is also a story of great hope in the face of terrible, terrible tragedy. The local people displayed such heroism."

Mazin finds comfort in remembering the courageous workers. "What you see is people behaving nobly and sacrificing for each other out of duty, out of love, and you begin to see this balance.

"I believe the truth is under assault," he adds. "It is a global epidemic, and social media is an accelerant for this fire. The cause is very human. We don't like uncomfortable truths, and this is about the cost of lies. I cannot think of a more relevant time to tell this story than right now."

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 4, 2019