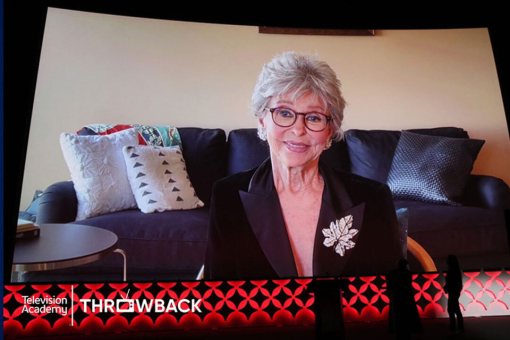

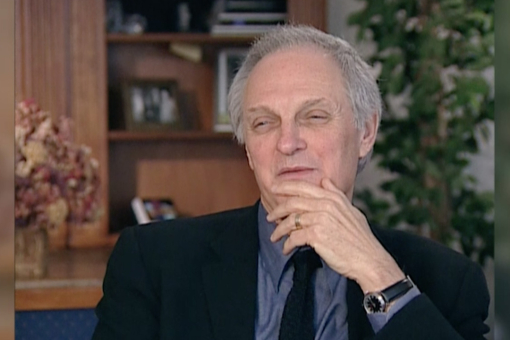

Alan Alda — the only human ever honored by the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences with Emmys for acting, writing, and directing — owes it all to burlesque. Well, a lot of it, anyway.

"I remember when I was nine years old and my father and I were rehearsing a sketch to do at the Hollywood Canteen," said Alda, reached at home in the pastoral bayside town of Willowbrook, New York, in the Hamptons. “The little hints he would give me came directly from his experience in burlesque. He would talk about how to approach a moment in the sketch, and he was dealing with it in the same way an improvisational performer would deal with it, which is often what burlesque comics would do. They had a basic sketch, and they would do jazz riffs around it.”

Strippers, comics, straight men, raconteurs — this was the company Alda kept through much of a childhood spent on the road with his father, actor Robert Alda, on the burlesque circuit of the 1940s. Alan debuted on stage at the age of six months, a crying or sleeping "prop" in a high chair playing foil to funnymen with names like Hank Henry and Rags Ragland. A dubious tutelage? Not to hear him tell it: “When you think about burlesque comics," he said, “most people don't think about them as being disciplined and creative. You think of them as filling in time between the girls. But I look back on the way they would create a character in a sketch over a period of years, adding little bits to it here and there. The development of a persona that was distinct and was original and had a uniqueness to it — that was very creative of them. … Not a bad model to have if you're trying to be good at your work.”

Alda seems a modest, even self-deprecating person, but he wouldn't likely argue with the assessment that he has been good at his work. Best known as Hawkeye Pierce in the beloved series, M*A*S*H (for which he won five Emmys in the show's 11-year run), the man has also won two Writers Guild Awards, three Directors Guild Awards, six Golden Globes from the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, and seven People's Choice Awards. For what many critics called his finest performance, in Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors, he won the D.W. Griffith Award, the New York Film Critics Award, and was nominated for a British Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor.

His acting achievements, of course, are well known. What is less known is his decidedly unusual, and often difficult, childhood. Aside from growing up onstage, where for several years he found himself competing with a pig for his father's attentions (more on that later), young Alda had to contend with a bout of polio at age eight, his mother's mental illness, and being an only child.

Asked to elucidate what was indelicately referred to as his "weird childhood," Alda merely exclaimed, "How dare you!" and laughed.

Asked how he managed to overcome trials of his youth and emerge well adjusted, he offered this:

"I didn't. I'm speaking to you from the top of the tower in Texas. There goes a nun!"

The answer, obviously, is in his lightheartedness. (He didn't get the role of glib, acerbic Hawkeye for excelling at sober drama.) In the spirit of indulging lightheartedness, well, what about that pig, Alan?

"The pig was part of a sketch where my father told fellow burlesquer Hank Henry that he was going out," said Alda. “And Hank said, ‘Don't come back until you bring home the bacon!’ And my father comes back in and says, ‘I brought home the bacon,’ and he's carrying this pig. The pig is just this one sight gag. By the way, I don't consider that much of a joke. But apparently, in those days 50 years ago, they thought that was hysterical. It got a big enough laugh to warrant carrying that pig around from town to town for a year or two. I think I was jealous of it. The pig got more attention than I did in some cases, because at least the pig got to go with the actors. Sometimes I got left with an aunt.”

But not so often that theater didn't become the preoccupation of Alda's young life. He still clearly recalls pivotal thespian advice his father gave him before that Hollywood Canteen sketch. They were doing Abbott and Costello routines (Alan, describing himself as having had buck teeth and having been "very fat," did the Costello parts).

"Neither one of us realized, I don't think, that he was tying me into an old tradition of steering by an internal compass," he said. “Oddly enough, that's almost the same direction I got from Woody Allen, 45 years later [in Crimes and Misdemeanors], Woody almost doesn't give you any direction. But when he does, he says ‘Don't say my lines the way I wrote them, that's very stiff and formal. Make it your own.’ The little direction my father gave me, was, I think, based on a similar thing, and went back to his working with burlesque comics.”

Considering his upbringing, the next bit of fatherly advice Robert Alda offered — when 16-year-old Alan told Pop of his decision to pursue an acting career — is fairly shocking. “My dad did pretty much the same thing I did with my kids. Two of them wanted to be actresses. What he did was to say, ‘You really shouldn't do it’ — and then he did everything he could to help me. Helped me get a job in summer stock when I was 16, a job in Rome when he was doing a play there — twice, when I was 18, then in my 20s. Well, I did that same thing with my kids. I discouraged them, then I wrote parts for them in The Four Seasons.”

After the job in summer stock, Alda entered Fordham College with the goal of becoming a classical actor. His fondest ambition? To play Oedipus. From Fordham, he acted at the Cleveland Playhouse on a Ford Foundation grant, then went on to years of struggle in New York. Throughout his twenties, frustrating times of "making rounds" in New York, Alda came to painfully understand why his father hadn't encouraged him to go into show business. During one lean period, Phil Silvers, and old friend from the burlesque circuit, helped him get a part in an "awful" off-Broadway revue.

Eventually, he did land decent off-Broadway, then Broadway, and finally television parts (he was a regular on That Was The Week That Was). Married at 21 and a father not long after, Alda was 29 before he realized that Oedipus probably wasn't in the cards. It dawned on him, dramatically enough, right in the middle of a musical in Boston called The Apple Tree, directed by Mike Nichols. Alda found himself on stage in tights and fright wig, playing a caricature of a rock 'n roll singer. As he once told an interviewer, “They pulled this sheet off my head, the audience looked at me and laughed as I did my song, and I gave up something in that moment. I gave up a fantasy of being highfalutin' and settled for what it was in me to do, whatever I could do well.”

He wound up nominated for a Tony Award for wearing that fright wig, and went on to his first movie role in Gone are the Days (a recreation of his stage role from Purlie Victorious). Then came parts in The Moonshine War, Jenny, The Mephisto Waltz, and Paper Lion. It was shortly after being nominated for an Emmy for his portrayal of Caryl Chessman (Kill Me If You Can) that Alda accepted the part that most defined his career. No great story here. The producers of M*A*S*H simply called him up and asked him to play Hawkeye. Alda, ever conscious of the social value of his work (this is, after all, the feminist who spent 10 years campaigning for the Equal Rights Amendment) did have one concern.

"We had to postpone our final talk till the night before the first rehearsal, so I hadn't really agreed to do it until we'd had our talk," he said. “I was making a movie about the Utah State Prison called The Glass House. That final talk was about an agreement that we wouldn't just do slapstick at the front. We would treat the war seriously. We would show that the war was a destructive force. When I realized that was what they wanted to do, too, we were fine and went to work the next day. I was concerned that we would do something like McHale's Navy, which would trivialize the experience of the people who had really lived through it.”

Amazingly, what became the staple M*A*S*H moment — the operating room scenes — were initially opposed by CBS. "The network wanted us to stay out of the operating room," he remembered. “They didn't want to see any blood. I mean, there was a real effort to keep us antiseptic and just be a bunch of crazy guys at the front, which was the very thing I did not want to do. Midway through the first season, when the guy died on the operating table, everybody realized that we could do things that had more substance than people first thought.”

A lot of laughing, and "never seeing daylight" are Alda's main memories of the 11-year run. "We would usually go to work before the sun came up, and go home after it went down. We were down in the mines." Perhaps his favorite moments were the two shows that featured his father. Alda wrote the scripts, which featured his dad as a good-natured but controlling surgeon ("kind of an inside family joke") who starts out in conflict with Hawkeye, but ends up teaming with him when wounds render Hawkeye's right hand, and the other surgeon's left hand, useless. They symbolically join hands for an operation. This part was Robert Alda's idea.

“What was nice about it was not only the image of these two surgeons carping at each other, how they have to come together and cooperate, but it was nice for a father and son to cooperate like that, to be right and left hand in same operation. I guess that's the last time we ever worked together. I like it that I could use his idea like that. We really were collaborating.”

He rarely watches M*A*S*H reruns these days and has no opinion about the series' place in television history: “That's for other people to say. I think it was a unique program in that there's never been, I don't think, one that had so much comedy in it but that was so much about life and death. The fact that we always tried to go back to what the real people had gone through, I think, kept us dealing with a version of reality that the audience could identify with. I think that's unusual, or unique, but I don't know anything about its role or place in television history.”

Neither does M*A*S*H co-star Wayne Rogers, but he did have observations to make about his friend of 25 years: “Alan's obviously very talented, and I can only tell you that desire to always make the material better and always do the best possible job is probably the only thing that exceeds his talent. Work is part of his life, not his whole life. It sets him apart a little bit from most of the people in Hollywood who are just ambitious, you know. He's also intelligent, well-read, and has a wonderful understanding of the human condition.”

That desire, almost a compulsion really, to understand the human condition is what prompted Alda to take his latest job — hosting the PBS series Scientific American Frontiers. Now in its second season, the show features Alda traveling the world to interview great scientists and translating their work into manageable terms for young people and lay persons. The longtime subscriber to Scientific American magazine loves the job.

"Science was not something I was interested in as a kid," he said. “I did very badly in a summer course in chemistry in college. I sort of lived the split that C.P. Snow talked about between the two cultures of art and science. I thought I was not in the scientific part of it. Although science has become more popular now, I think there are still people who think that because they are interested in literature that automatically excludes an interest in science. And I think one of the things this program may do is help break that down for young people.”

Alda is 56 now, a grandfather, and habitually embarked on any number of projects and pursuits. Fluent in Italian and French, he has lately been teaching himself Chinese and Yiddish. “My goal in any language is to be able to make jokes in that language. I have done it in Chinese, but it was labored. Somebody heard me talking Chinese, and said I sounded like a Tibetan monk. That I had the accent of a Tibetan monk. I take it as a compliment, but I don't think it was meant that way.”

His major preoccupations at this point in life, he will tell you, are his wife Arlene, a professional photographer, daughters Elizabeth, Eve, and Beatrice, grandson Scott, and granddaughters Emilia and Isabel.

Not to suggest that new work doesn't loom: I'm thinking just as much about what projects I might do next as I ever did," he said. "The only difference is that I don't feel driven to do something next. I'm taking pleasure in looking for what I really deeply want to do next."

Does he feel hoary enough to be inducted into the Hall of Fame?

"Well, I tell you, it's nice," said Alda. “I know a lot of people think, ‘Oh my God, Hall of Fame, this must mean I'm dead. Or that I'm not going to ever do anything again!’ I like it. I've just been nominated for another Emmy for And The Band Played On. And White Mile [an HBO movie] is the best work I've ever done. What's nice is there isn't anything about my life that makes me wonder if this award is a signal that things are grinding to a halt. I've never been busier and I've never been happier working. I can just enjoy it. I feel very good. It's a great honor. I mean, there's a lot of people that have worked in television. That this group thinks I should be singled out is a tremendous compliment.

He timed the next line like a burlesque comic.

"I mean, I can enjoy it without wondering if I'm still alive."

This tribute originally appeared in the Television Academy Hall of Fame program celebrating Alan Alda's induction in 1994.