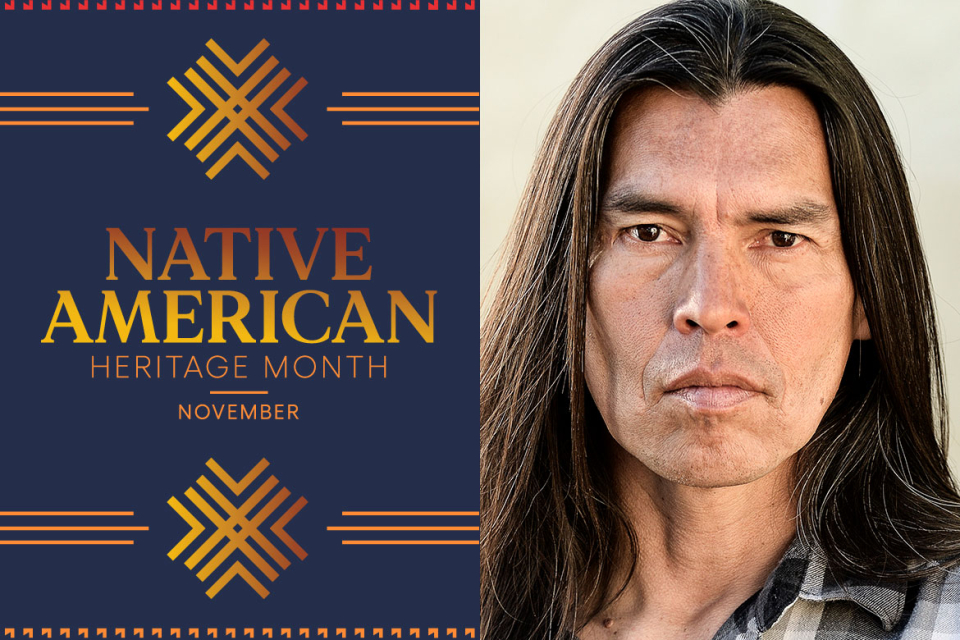

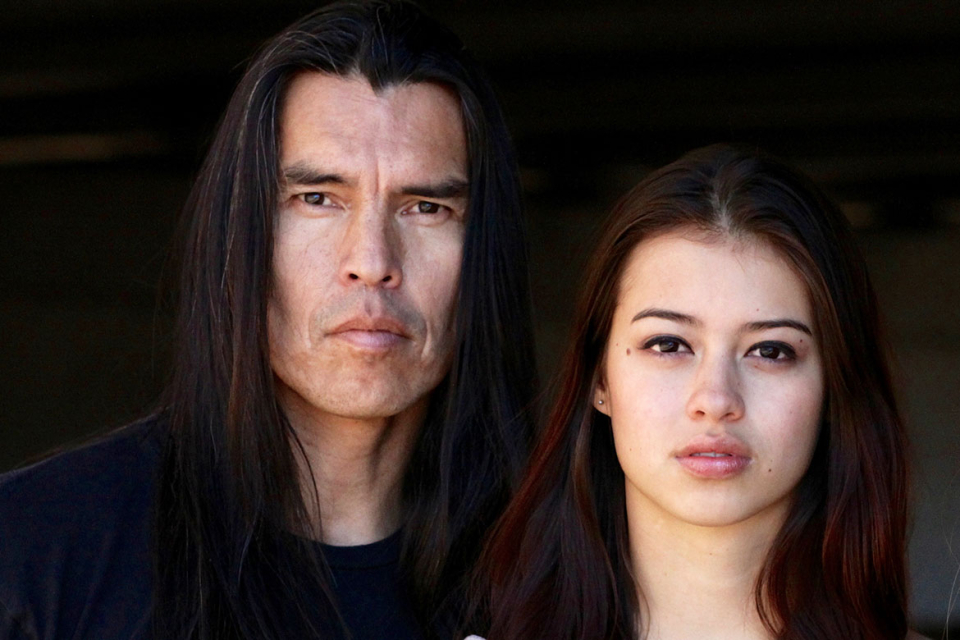

"Have you seen pictures of me?" David Midthunder (Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux Reservation) asks during a phone call from his Santa Fe-area home.

It's rather a rhetorical question. Audiences have seen much more than still photos of Midthunder during a 30+ year career on the big and small screens in projects including Westworld, Longmire, Hostiles, The Lone Ranger, The Book of Eli, The Last Stand and Maleficent: Mistress of Evil.

He asks because we are talking about acting opportunities, and he has what he calls a "stereotypical Native look" and therefore doesn't get many roles that are non-Native. Those sorts of parts, the ones that are not necessarily defined by one's ethnicity, are often considered a kind of Holy Grail for actors. Many point to Wes Studi's portrayal as a cop in 1995's Heat as a prime example.

"When you watch films with Native content, it's typically historical. We are such a small 1% of the population, a lot of what people think they know is what they see on TV. When they see modern Indians out there surfing, dirt biking, rock climbing and having fun, they don't know we're like that," Midthunder says.

"For me, what really inspires me is the first time I saw the 1976 film Car Wash. Henry Kingi was a modern Native man living in downtown LA and working at a car wash. I liked seeing that."

Midthunder also points to 1998's Smoke Signals as a contemporary film he admires, one that defined the essence of the modern Native community.

"I'm typically not the doctor or store manager. If it's a period piece, I'm Native, or if it's contemporary, a rancher or that kind of role. I think it's starting to change. I'm thankful for what I have," he says, invoking the Lakota term Wopila, meaning sharing thanks for all of existence and the blessing inherent in each moment of it, or as Midthunder defines it, a mindful and careful way to approach life.

Wherever his career has taken him, he looks for the positive aspects in it. "I figure out why this was washta [good], and made me stronger. When I went to boarding school, until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, through all the generations we couldn't practice our religion.

"It made me more determined to hold on to traditions and go to ceremonies. By looking at everything washta, it made me tougher, more resilient, when I look at Hollywood or my career."

Midthunder got his start in the industry in a kind of modern-day discovery at Schwab's drugstore way. It was accidental. He was studying cultural anthropology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City when he was approached – he says clearly because of his looks – to ride horses before the university's football games.

At one of those games, some production people were in town making a movie and spotted him, then offered him a job. He wasn't really interested, as he'd never thought of acting, but for the $5-$600 the film people quoted for an action scene, thought he'd give it a shot.

A SAG card and an agent soon followed. He began studying the business of entertainment and getting advice from other Native actors about its pitfalls as he began auditioning and getting a lot of jobs. One of the perks he enjoyed was the travel, something he’d done with his family growing up, as his father worked for the federal government’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

“I was born in Montana, just west of the Cheyenne tribe and in the late 60s and early 70s we would go to powwows, whose ceremonies weren’t still out in the open, with the Pawnee Nation in Oklahoma, the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho and the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians in Palm Springs,” he remembered.

“Those days were a hotbed of Red Power. When we were in the Bay Area or Sacramento, we would go from reservation to reservation to go back to Montana. We would go to places we knew were safe to gas up and eat at restaurants. Native spirituality brought my family through difficult times.”

Over the decades, he's seen many changes for the better in the way Native and Indigenous people are portrayed on screen.

"I think the old Westerns of the 40s, 50s and 60s showing a male warrior on the warpath attacking white people didn't show this guy trying to get revenge for his people being decimated as they invaded his homeland. Instead it looked like a bloodthirsty killing of white settlers. Audiences didn't know the reasons. There were misconceptions.

"We were families living there, wives, children, grandchildren. We were patriots fighting to protect family and homeland."

The recent racial reckoning that has shaken this country and many others across the globe gives him reason for more optimism.

"The feeling I'm getting is we've always relied on our resilience. We all stand together, all colors, if we talk about injustices, whose voice is getting louder? I hear it getting it getting louder and more articulate," Midthunder says. "Things are changing. There are new ways of looking at some of the [New World] discoverers. Were they really heroes, or just trespassing? Anger also can be turned into energy. Why is the anger good? It's a motivation."

Read more on Native American inclusion in the television industry.