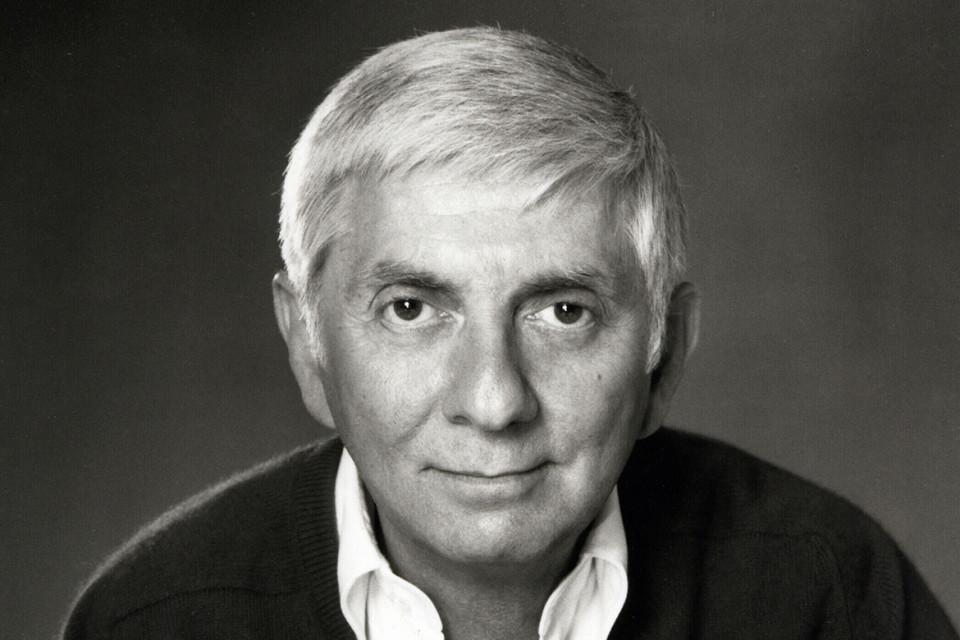

In this 1995 interview for emmy magazine, Aaron Spelling describes his humble beginnings growing up in Dallas, Texas, where he was known to his friends simply as "Skinny."

The writer–producer, who was seventy at the time of this interview, made his way into show business by directing plays, one of which caught the attention of writer–director Preston Sturges (Sullivan's Travels). The auspicious meeting led to some small acting roles for Spelling, on series like Dragnet and I Love Lucy.

He earned his first TV series producing credit on Johnny Ringo, a show he created about an ex-gunfighter who becomes the sheriff of a small Western town. Over the course of Spelling's career, he would amass more than 230 producing credits and win two Emmy Awards. The first was in 1989 for Day One, a television movie about the race to build the atomic bomb, and the second was in 1994 for And the Band Played On, a television movie about the AIDS epidemic. He was nominated five more times between 1970 and 1982 in the category of Outstanding Drama Series, for The Mod Squad, Family and Dynasty.

One of his most enduring series, however, was Melrose Place, a primetime soap opera about a group of friends living in an apartment complex in West Hollywood, California. The Fox series, created by Darren Star (Sex and the City; Beverly Hills, 90210) premiered on July 8, 1992, and ran for seven seasons. The series featured a frequently changing cast including Heather Locklear, Andrew Shue, Courtney Thorne-Smith, Thomas Calabro, Josie Bissett, Doug Savant and Marcia Cross.

The show was rebooted in 2009 with a new cast of young professionals living at the Melrose Place apartment complex, but only ran for one season on the CW.

Spelling continued to accrue executive producing credits with his long-running series 7th Heaven and Charmed, up until his passing in 2006 at the age of eighty-three.

In celebration of the thirtieth anniversary of Melrose Place, revisit this emmy magazine interview with Aaron Spelling, Hollywood's most prolific TV producer.

Forget the Aaron Spelling who's produced more hours of television — over 3,000 — than any person in history.

Forget the Spelling who's been sneered at as TV's schlockmeister for series ranging from Charlie's Angels to Melrose Place but also has won two Emmys in four years for serious TV movies — Day One (about nuclear disaster) and And the Band Played On (about AIDS).

Forget the multimillionaire Spelling, seventy, whose forty-five-room Holmby Hills estate is one of the largest and most sumptuous in southern California and from which he personally emerges to chat with the tourists pausing at his gate in sightseeing buses.

Consider instead how Spelling evolved from a kid called Skinny into the megamogul he is today. It is a little-known story — withheld, perhaps, for Spelling's own use in a book he is planning, but revealed to me in old friend-type talks.

For starters, he says, "You know, in one of the Mod Squad episodes, I gave one of my characters the line 'I was born in a six-thousand-dollar house with one bathroom and wall-to-wall people.' With that line, I was talking about my own childhood in Dallas."

It's difficult to think of Spelling being poor at any stage of his life, but in the 1920s, it was wall-to-wall poverty for him. "My father, David, was a tailor and didn't make much money, even before the Depression. Tops, he earned forty dollars a week. That little house was on an unpaved street in Dallas. In addition to me and my mother and father, my brothers Max, Sam, and Danny lived there, also my sister Becky and her husband. My aunt lived in a house next to ours. On the other side was a house with a sign in its window, FIFTY Cents and a Dollar. When I got old enough [he was the baby of the family], my brothers told me it was a whorehouse."

Being the youngest, Spelling profited from the help of his brothers as they got old enough to hold jobs. They made sure he went through high school. They then encouraged him to go into the army so he could go to college on the G.I. Bill, which he did. His college of choice was Dallas's best, Southern Methodist University.

While at SMU he got involved with the Reuben Theater in Dallas, a local amateur playhouse financed by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. At the time, everyone called Spelling "Skinny," a nickname that remained with him until after he made his first million.

Skinny ended up directing one play a month at the theater, though he really wanted to be an actor. Penniless, he decided he had to make some money out of his predilection for the theater, and that the only place to make money was in Hollywood. He came by bus.

"I was so broke after laying out the money for the bus fare, that I took the first job I could get. The job was selling airline tickets at Western Airlines, and I lived in a cheap, cheap apartment in the cheap, cheap part of Hollywood."

One day, a former Variety reporter named George McCall came in to buy tickets for his wife's touring band. His wife was Ada Leonard and her band was Ada's All-Girl Orchestra.

"McCall and I got to talking at the ticket counter," Spelling says, "and he seemed to like me. He asked what my name was, and I said, Skinny. He said, 'Do you like this job, Skinny?' I said no. He said, 'I'm looking for a band boy. Would you like to come with us?' I didn't know what a band boy was, but it sounded like show business, and I said sure. So I ended up schlepping the heaviest instruments for the band from place to place — cellos, drums, guitars."

Spelling rose to the role of talent scout for the show, which aired as an all-female amateur hour on KTLA in Los Angeles. "Every kid in the [station] mailroom wanted to be an actor, and they entered a one-act play contest. They knew I had directed some amateur plays back in Dallas, so they asked me to do the same for them. I wrote and directed the play, and we won the contest. Flush with victory, the mailroom boys asked me to do a three-act play. I came up with Garson Kanin's Live Wire which we did in a little forty-five-seat theater over the bus station on Cahuenga Boulevard."

"For some reason," Spelling continues, "the Los Angeles Times reviewed our production quite favorably, which brought in director Preston Sturges, who moved us uptown to his theater on Sunset Boulevard. The funny thing is that of all the mailroom guys who wanted to be actors, I was the only one to become an actor out of this. A man came up to me in the theater and said, 'You're a good director. Can you act?' 'Certainly,' I lied. As a result of this brief conversation, I got small acting roles in such TV shows as Dragnet. The money wasn't much, and I still was living in that cheap, cheap Hollywood apartment. By now I really wanted to write, and I kept submitting scripts on speculation to TV producers, always getting turned down."

Then came an acting role in a movie, Vincente Minnelli's Kismet. It was only one line, but it paid much more than his TV work.

"When I tried out for the part," Spelling recalls, "Minnelli said, 'Ah, a young skinny one. That's good.' At the time, I was dating Carolyn Jones, who became my first wife. She knew a lot about acting, having done more than a dozen films by then, at Paramount and Columbia studios. She knew Minnelli and came to MGM to watch me do my one line in Kismet. Afterward she came to me, shaking her head, and said quite firmly, 'You'll never act again. You will write.'"

That was the end of Spelling's abortive acting career. He resumed sending scripts to producers. One of them found its way to what was then Four Star Studio, where the successful TV series Zane Grey Theater was produced, at the height of the Western craze in both movies and television.

"They called me and asked me to come in with samples of host spots," says Spelling, "sort of introductions for the host of each episode of the anthology series. I hated the idea, but I brought in some hastily written spots anyway. They didn't ring a bell with anyone — except Dick Powell, one of the owners of Four Star. He said to the others, 'Here's a good one: He stole a cow that wasn't his'n; was hung before he got to prison.' And I was hired, at $125 per spot."

Powell, a very hot actor at the time, became Spelling's guardian angel at the studio. As Spelling tells it, "After I sold a story idea to Jane Wyman for $300, my first real writing fee, Powell said, 'Hey, Skinny, why don't you write a script for us?' I did, and he liked it. He said, 'Skinny, you're going to be producing this show for us some day, won't you?' I laughed, but in three years it was so."

Spelling produced Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theater (as it came to be called) until its demise in 1962. "Dick and I became veiy good friends," Spelling recalls. "I even used to take Dick's kids over to Ronald Reagan's house to play with his kids. It was a sad day for me when Dick died in 1963. I was outraged when, two days later, the studio removed Dick's wife's name — June Allyson — from her parking spot. I was so outraged that I quit Four Star."

He did not lack for work, however. Playhouse 90 wanted to do a Western and they grabbed Spelling to write it. The day after the show aired, Twentieth Century Fox bought the same story for Spelling to rewrite as a movie feature. By now he was a William Morris Agency client and a favorite of Abe Lastfogel, head of the agency and known to all his favorites as Uncle Abe.

At this point, Spelling's days of poverty were well in the past. Lastfogel sent him to New York to head a new television department for United Artists. "By the time I got there on the train," says Spelling, "they had changed their minds about going into television, but I had a signed contract and they had to pay me for doing nothing. That's how crazy TV was in the 1960s."

Even crazier, Spelling got back to Los Angeles and was having dinner the next night at La Scala with Candy, his soon-to-be second wife, when a voice roared at him from across the room, "Hey, partner! Hey, partner!" Spelling peered in the direction of the roar and saw that it was Danny Thomas. "Danny summoned us to have a drink with him, which we did, and he said excitedly, 'Did Uncle Abe read you in New York?' I said no. Whereupon he picked me up — I was and still am skinny — and swung me around. He bellowed, 'You're my partner in my new television company!'"

And that's how the very successful Thomas-Spelling TV production company was born.

It was a profitable melding of talents, which lasted from 1969 to 1972. In those three years Thomas-Spelling produced a dozen TV movies and had six series on the air. Chief among them was Mod Squad, a huge hit for five seasons on ABC. The genesis of this show exemplifies a unique Spelling habit that exists to this day. "I don't talk much to my colleagues in television who live in Bel-Air and Beverly Hills, because when you ask them which TV shows they watch, they always say PBS when they're closet viewers of sitcoms like Roseanne and The Simpsons."

"I don't fly, because years ago I was supposed to be on one that crashed. So I always drive or take trains, and I do a lot of talking to common people in coffee shops and such along the way. That's how I got the idea for Mod Squad and, later, The Rookies. People kept telling me they loved cop shows on television, but all the cops were forty and older. 'How about young cops?' they said, and that's how Mod Squad came into being." Spelling's latest youth-movement shows (Beverly Hills 90210, Melrose Place) evolved from ideas similarly derived.

After Thomas-Spelling came Spelling-Goldberg (Leonard Goldberg had been a top programming executive at ABC), which lasted from 1972 to 1976. This was the millionaire-making period of Charlie's Angels, The Love Boat, Family (an Emmy winner), Starsky and Hutch, Hart to Hart, Dynasty, Fantasy Island, et cetera.

In 1972 Spelling founded Aaron Spelling Productions. Today it is called Spelling Entertainment and is 78 percent-owned by Viacom, which put it up for sale last August. (As of press time, the company had not sold.) Through it, Spelling produced his two Emmy-winning TV movies, Day One and And the Band Played On, his answer to those who still hurt him by labeling him as strictly a purveyor of voyeuristic schlock. He has had two hit series on the Fox network, Beverly Hills 90210 and Melrose Place, with Central Park West new this fall on CBS. Spelling International Films has several theatrical films in or near production with such big-name movie producers as Oliver Stone.

He admits, however, he made one blooper, a series called Nightingales. It was about student nurses, but most of the scenes displayed the women in various stages of undress in their locker room. It was a ploy that worked in Charlie's Angels, but it didn't work here. Loud protests from real nurses and women in general soon drove Nightingales off the air.

Spelling is a firm believer in the Rodgers and Hammerstein South Pacific axiom, "You gotta have a dream." He urges people to stick with their dreams, because "at least some of them can come true."

One of his favorite utterances about his own dreams is, I took the Love Boat and landed on Fantasy Island. In fact, "he says, that may be the title of my book."

Not bad for a skinny kid who started out selling airline tickets.

Bill Davidson is a former contributing editor of TV Guide.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #6, 1995, under the title, "The Evolution of Aaron Spelling."

To watch Spelling's Foundation Interview, go to: TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews