When Jane Curtin got her first taste of stardom, as one of the original cast members of NBC’s Saturday Night Live, she didn’t like it much.

“I didn’t go anywhere,” she recalls. “If I did go somewhere, I tried to be as invisible as I could. There was so much hype about us [the cast] and so much hype about the show that people felt the need to challenge us. You’d be walking down the street, and they would confront you. It was very difficult dealing with people’s responses to us.”

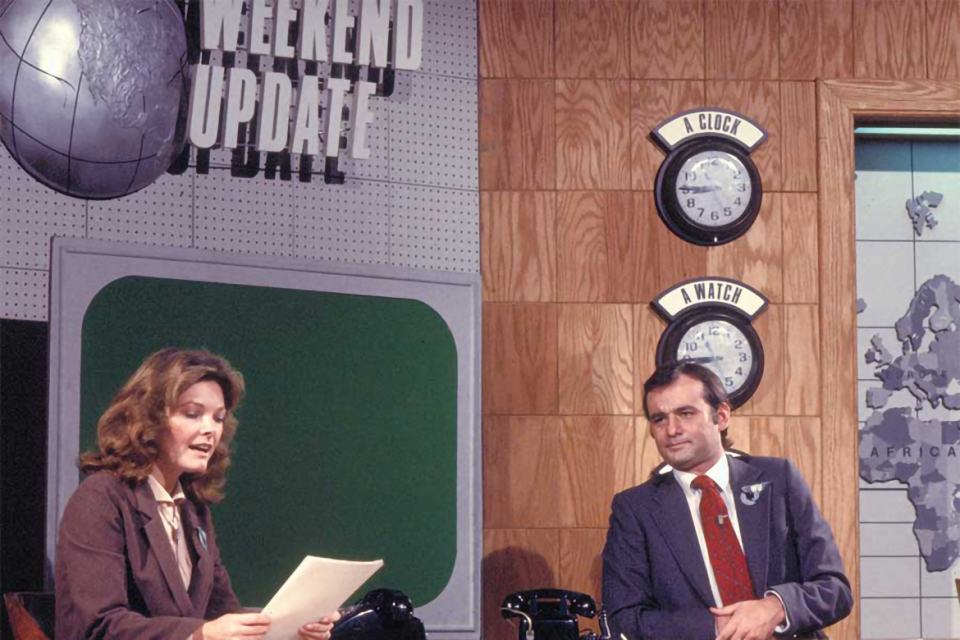

Unlike many of her castmates, Curtin came to SNL as a newlywed who was not into the party scene. Still, her barbed wit and nimble reactions in improv kept her on a solid footing among a cast that would become legendary. During her five-year run, she appeared in the show's signature "Weekend Update" and the renowned Coneheads skits.

Curtin — who would go on to star as single mom Allie Lowell in CBS's Kate & Allie and as anthropology professor Mary Albright in NBC's 3rd Rock From the Sun — was interviewed in May 2015 by Jenni Matz for the Television Academy Foundation's Archive of American Television. An edited excerpt of that discussion follows; to view the entire interview, please go to televisionacademy.com/archive.

Q: In 1975 you became part of the original cast of Saturday Night Live. How did that come about?

A: I had left [my improv group] The Proposition and was off doing other things. I got a job touring with George Gobel in Last of the Red Hot Lovers, which was pretty fun.

I came back to the city and was auditioning and somebody said, "There's a show that's going to happen — we're not really sure what it is, but we think you'd be right for it.” I thought, "I don't want to audition by myself."

So I contacted two of my friends from improv, Sam Freed and Munson Hicks, and said, "Have you guys been called into this show?" They said yes. So I said, "Let's go in and do improv together." We did and it was fun. I thought we were great.

Q: What happened?

A: I was asked back, but they weren't. When I was called back, they said, "We just want to talk to you — you don't have to do anything." Once I was there, they said, "Have you prepared anything?" I said no. That was the classic anxiety dream.

Then I remembered that I had something in my purse that I had written with someone else for a CBS test, so I said, "Wait a minute! I have something in my purse." So Gilda [Radner] and I read it, and I got the job.

Q: What do you recall about working with the first host, George Carlin?

A: I loved that man so much. He made a big thing about coming to see Laraine [Newman], Gilda and me before the show and giving us roses, saying, "I hope you have a lovely show and good luck." It was so thoughtful and kind, What a generous, amazingly brilliant man he was. I'm sorry he's gone.

Q: What was it like in the writers' room?

A: Didn't go there. I would go in on Wednesday for the read-through and just hope against hope that somebody had written something that I was in, but I didn't know from week to week if that was going to happen. It wasn't until I got "Weekend Update" that I felt as though, "At least I have this to do, and anything else is gravy."

Q: Chevy Chase broke out early as the star. What was your interaction with him like?

A: He could present himself in a way that was funny and accessible. When he entered a room, the room changed — he had that ability — so it made sense that he would be the face of the show. But then the face became this really big face, which ticked a lot of people off. John [Belushi] wanted to be the face, and other people wanted to be the face. So it was tense when that happened.

Q: How would you describe John Belushi's talent? And what was it like working with him?

A: John and I were trying out for Howard Cosell's show [Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell], so we would take a cab together back to the Village — he didn't live far from me. He was just another actor who was looking for work. He had a lot of promise, and he was very sweet and considerate. We would sit on my stoop and talk about what we wanted out of the business,

He was married, I was married, we liked our lives. Then, when Saturday Night Live started, I saw that something had gotten to John — I don't know whether it was ego or ambition or if it had to do with drugs. He was no longer this guy I could relate to.

Working with him was hard because he didn't respect me. At least, he appeared not to respect me, and he didn't seem to respect the other women on the show or the women writers.

Q: You've talked about a boys' club atmosphere in the early days of SNL. How did you and the other women cope?

A: It was pretty palpable. Chevy actually said to me one day in rehearsal, "Does your husband ever get upset at you doing things like this?"

We were playing a married couple — the Supreme Court was in our bedroom, and we were in bed. I said no, and he said, "Really?" I said, "Well, he was an actor at one point. No, he doesn't. Would you get upset if your wife did this?" He said, "Yeah, I would." These guys came from a different place, and they just didn't think they should be competing with women. They didn't think that was right.

Q: What do you remember about working with Gilda Radner?

A: I loved Gilda. She and Laraine and I shared a dressing room the first year of the show. She would lead the conversation. She was amazing. She had so much to put out there — I'm a New Englander, I don't put everything out there. But watching Gilda and the effect she had on audiences and on everybody in the room — not many people have that gift. The audience lapped it up.

Q: What about Laraine Newman?

A: She was so young. She was trying to be happy and excited, but she was homesick. I think she was 21 when she came to the show. I wanted to be protective of her, but the pressure was huge and everybody responded to it in a different way. It was hard watching her be so sad.

Q: What about Garrett Morris?

A: Garrett was in a tough position. He was originally hired as a writer and then became a performer, but he didn't do improv. He did not come from that facile place that most of us came from. And they weren't writing for him, they weren't including him in scenes.

At one point [head writer] Michael O'Donoghue — whom I adored but was a difficult guy — wrote a sketch about the Titanic. They had filled up the dining room of the Titanic with extras and cast members, and he was furious that Garrett was there.

He said there were no black people on the Titanic. He was furious that there were Jews. "There were no Jews on the Titanic!" I'm thinking, "Okay, it's comedy. You're not doing Masterpiece Theatre. Garrett should be in these sketches. He's fun. He can do the job — let him do it."

Q: What was it like to work with Dan Aykroyd?

A: Dan was probably the easiest to work with. Dan and I were workhorses. We got this job, and our job was to do it to the best of our ability and not create problems.

So Dan and I liked working together because there was no drama, We felt very comfortable being together in scenes. Off camera, we have a very hard time carrying on a conversation, because we're such different people. But I adore that man, I do.

Q: You took over "Weekend Update" from Chevy....

A: I was thrilled they asked me to do it. I had done commercials, so I think that was one of the reasons they asked me, because I could deal with the camera. I felt very comfortable up there, and I was working with the person I probably respected more than anyone on that show, Herb Sargent, who wrote "Weekend Update."

Q: How did the energy change when Bill Murray came on as your co-anchor?

A: I love Bill Murray. It's nice to bring different energy into a situation, and Bill's energy certainly was different from most. But it was welcome — Bill always kept you on your toes.

There were times when the stage manager would be counting down, "Five, four, three..." and Bill wouldn't be there. And when he got to one, Bill was there. I always knew he was going to be there. People were freaking out — I don't know what he was doing — but he always got there on time. He never let me down.

Q: Let's talk about some of the sketches. How hard was it to get in and out of the costume for Coneheads?

A: It was hard. The problem was that we never had any time when we were doing the show, and the props were very heavy. They would put spirit gum all over you and then stick on [the cone] and put putty around the edges. You'd go out and do [the skit], and then they would have to rip it off. So you'd have welts.

I hated putting them on. [I'd say,] "Please don't glue it. I promise I won't move my head." But they had to.

Q: You got to work with Buck Henry on the Nerds sketches....

A: My character, Mrs. Loopner, was based on a woman I met walking my dog in New York. She had a dog, and my dog and her dog would play. Nothing ever bothered this woman. She'd say, "Oh, my dog just had a terrible tumor removed from her skull." She thought everything was hysterically funny, so that became Mrs. Loopner.

Q: There are so many stories about the legendary after-show parties, but you kind of stayed out of that....

A: That was the height of the drug culture, so drugs were everywhere. Cocaine mostly. Once you'd done the show for 90 minutes, and it ended at one in the morning, you weren't able to go right to sleep. So you had to have something to bring you down.

I stopped going to the parties because they weren't fun. It was mostly a postmortem, and there would be writers walking around severely depressed. Then you'd be sitting next to a rock star who had his fist in his nose and you're thinking, "Okay, I think I'm going to go home."

Q: How was it working for Lorne Michaels?

A: I had very little to do with Lorne. I had an encounter with Lorne once when John [Belushi] was a little out of control and was going through my stuff. I told him,"I don't know what to do. The guy needs help. He's going through people's purses looking for pills or money or whatever. It's not good."

It fell on deaf ears, so I thought, "I'll leave you to do your thing, and I'll do my thing and we'll be fine." The time on "Weekend Update" when I was supposed to rip open my shirt, he didn't ask me to do it directly — he asked Gilda to see if I would be willing to do it. I went, "Yeah, yeah." We had very little contact with each other.

Q: Why did you decide to leave in 1980?

A: My contract was up. And everybody was leaving. It had run its course, as far as I was concerned. I couldn't give any more. I was spent. It was five life-altering years of extreme pressure, extreme stress and extreme fun. All of that takes its toll.

Q: How did you deal with the fame?

A: I didn't go anywhere. If I did go out, I tried to be invisible. My husband [Patrick Lynch] and I went out to dinner once with my parents and his mother. We walked into this place in midtown, and there was a bunch of young executives having a beer. We knew the people who ran this restaurant, so they greeted us warmly. But these guys at the table started ripping me to shreds.

Q: About what?

A: Saying things like, "Well, she's not so great. I mean look at her — she's chunky." There was so much hype about us, so much hype about the show, that people felt the need to challenge us. You'd be walking down the street, and they would confront you. It was very difficult.

Q: What is the legacy of your five years on the show?

A: We got the outline for the show in place. It was very different in the beginning from what it is now. I think our legacy was the idea of bringing live television back.

As far as the comedy was concerned, it was a little more pointed, a little rougher. It was less of the Red Skelton, Henny Youngman, "Take my wife" kind of humor. It was broader and more encompassing of life and politics and culture.

Q: Let's move on to 1984's Kate & Allie. How did that show come about?

A: It was presented to me as a series called "Two Mommies" — instantly I wanted to barf. I didn't want to do it. I thought it was stupid. They said, "Just meet the director." I met Bill Persky, but I was still thinking, "I should be doing something much more important."

Then my agent said, "They're going to pay you this amount of money," and I thought, "Okay, I'll do it." It turned out to be really fun. I worship the ground Bill Persky walks on. I think that man has done a tremendous amount for television.

Q: Do you think the show portrayed something — two divorced women moving in together to raise their children — that was going on in American culture?

A: Apparently it did. We got a lot of feedback from people, especially a lot of older men who saw their daughters in Kate and Allie. All of a sudden we were legitimizing single mothers, saying, "Yes, this happens." These women have to go on, make a life for themselves and their children, and this is a great way for them to do it.

Q: You returned to series television again in 1996, with NBC's 3rd Rock from the Sun. How did you get involved with the show?

A: My phone rings and it's Bonnie Turner [one of the writers of the Coneheads movie]. I said, "I hear you're doing something with John Lithgow, How's that going?" She said, "Well, we shot the pilot, but it didn't really work." I asked why and she said, "We have one character that really should be two, so we're going to have to reshoot it. Maybe you want to come out and do it?"

Q: What did you love about the show?

A: The silliness. And the fact that during the read-throughs, you couldn't control the tears because you were laughing so hard. It was one of the funniest things I've ever done in my life Loved it. Loved every minute of it.

Q: What would you tell others who want to get into acting?

A: That you might not get everything you want, but there's so much within this business that you can do. This business is so welcoming. If you want to start acting when you're 50, chances are pretty good you're going to get a job. They always need 50-year-olds, 60-year-olds.

A friend of mine knew a college professor whose wife had died and he had retired. He bought a motorcycle, drove to New York City and called my friend, asking if he could sleep on his floor. He said, "I think I'm going to be an actor." Within a month he had gotten a job on Broadway and he won a Tony! So don't give up.