Not many filmmakers begin their career with an Academy Award nomination. but that's what happened to Lesli l:nka Glatter.

Her first film, a short called Tales of Meeting and Parting, was Oscar-nominated in 1985. In the decades since, she has crafted a directing résumé replete with episodes of Twin Peaks, Ray Donovan, The Walking Dead, ER and The West Wing, among many others, as well as pilots such as Gilmore Girls and Pretty Little Liars.

She has also become a sought-after producing director, serving as both an executive producer and director on series such as Homeland. For her work on the Showtime drama, she's earned six Emmy nominations, four for directing and two for producing, plus six DGA award nominations and two wins.

The Texas native started her professional life as a modern dance choreographer, which took her around the country and to Europe and Asia. She ended up in Los Angeles, where she brought her storytelling skills to television.

She earned her first Emmy nomination for directing the memorable Mad Men episode "Guy Walks Into an Advertising Agency," which reveals the unintended consequences of bringing a John Deere tractor into the Sterling Cooper office.

"When I first read Matthew Weiner's amazing script, I thought, this is either going to be fantastic or a total disaster," Glatter recalls. "It was risky and challenging but simultaneously exhilarating, because nothing like that had been on that show."

With Homeland approaching its final season, Glatter remains an executive producer–director while she shepherds other projects through development, including Pieces of Her and The Banker's Wife.

Glatter was interviewed in May 2018 by Amy Harrington for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire discussion can be screened at TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

Q: How did you get into the industry?

A: I got a grant to teach, choreograph and perform modern dance throughout the Far East and was based in Tokyo.

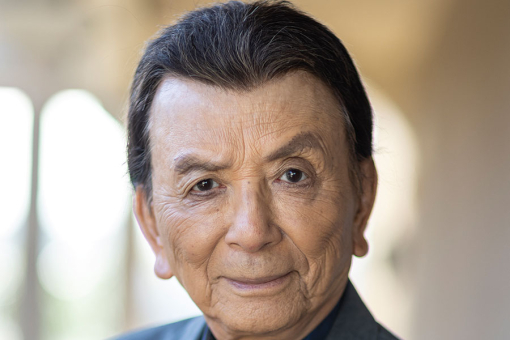

One day I wanted a cup of coffee, and there were two coffee shops — one on the right and one on the left. I arbitrarily picked the one on the right, and little did I know that it would change my life. There was maybe one seat open, and it was with an older Japanese man — I was 25 and he turned out to be in his mid-70s. He waved me over, which was a bit un-Japanese, and I sat down at his table.

Yutaka Tsuji became like my Japanese father and mentor. We had this extraordinary conversation that day in the coffee shop, and he and his wife kind of took me in. Years later he told me a series of stories that happened to him, all on Christmas Eve — even though he was Buddhist — during different wars and about human connection.

The stories were so powerful that I knew I had to pass them on, and I knew it wasn't through dance. Those stories became my first film.

Q: So did you come back to L.A. to attend AFI and make the film?

A: I was married at the time, and my husband was coming to L.A. for work. I'd never been there before and was skeptical, but ended up getting a job teaching and choreographing at California Institute of the Arts.

But Tsuji's stories kept haunting me. A friend told me about a program at AFI, the Directing Workshop for Women, but I was ineligible as it was set up for women in the film business who hadn't directed. I was not in the film business and didn't know anyone in the business.

I therefore was completely unqualified, but I applied anyway. And luckily, that year they let in a choreographer — me — and a theater director.

Q: How did that program prepare you to become a director?

A: It was a grant program, and most of the women were very experienced. At the first meeting, it became very clear to me that I didn't know anything about how you make a film. But dance is a great background to come from because you can't cheat — your leg goes up in the air or it doesn't. I realized, "I have got to work on the other women's films to learn about this process."

So I worked on ten of the other women's films. I story-boarded my film probably five times, because I needed to practice visualizing it in my head. Then I got myself into an acting class with the incredible Joan Darling, who I was just an advisor with at the Sundance Director's Lab.

Ironically, I was told not to make this film if I ever wanted a job in Hollywood, because it was three-quarters in Japanese, with subtitles. It also had flashbacks, narration, was a period piece set in World War II and had one Caucasian character! But I didn't care, as it was the story I wanted to tell.

Q: Did you get any mentors out of that program?

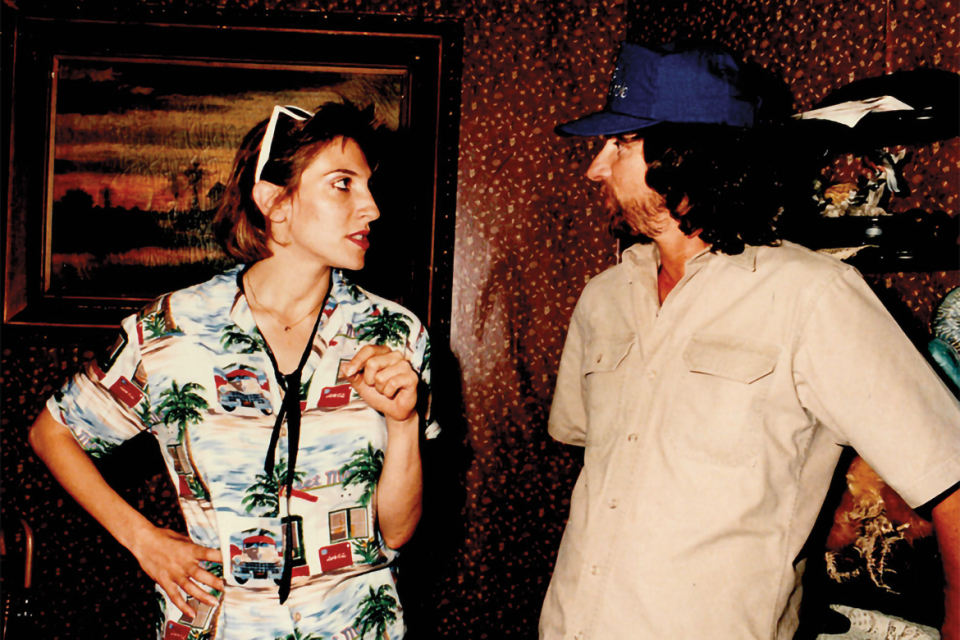

A: Yes, I have had wonderful mentors. After the film was [Oscar] nominated [for Best Short Film, Live Action], I got a call from Steven Spielberg. I thought it was a fake call, so I hung up on him!

Fortunately he called back. He had seen my film on an airplane. He called me in for a meeting as he was starting an anthology series, Amazing Stories, and was having very well-known directors directing each of the episodes.

But he was also going to pick three new directors to come on, and I became one of them. That was my real film school, because I got to shadow Steven as well as Clint Eastwood.

These two giant filmmakers — who have completely different ways of working, stylistically — taught me so much. One of the things I learned is that there is no right way, that you've got to find your own path. I ended up directing three episodes of Amazing Stories.

Q: You then started to direct a long list of television shows, TV movies, features, specials, pilots….

A: I think my next job was Twin Peaks — what an amazing thing to walk into! I went with a friend to see the premiere of David Lynch's pilot, and I was blown away. It was so observant and funny and unique and visual. Lynch is an extraordinary visionary filmmaker and couldn't be more different than the two filmmakers I had been shadowing.

One of the seminal moments was a scene, which David directed, with Michael Ontkean and Kyle MacLachlan in a bank vault. And in the middle of the table is a moosehead. The camera never moves. Michael and Kyle are on opposite sides of the table, and they have this whole conversation, but no one ever refers to this moosehead.

As I got to know David, I asked, "How did you get the idea to put that moosehead there? It's genius." He looked at me strangely and said, "It was there." The set dresser was going to hang it on the wall, but he saw it there and he said, "Leave the moosehead."

That was another important learning experience. As much as you try to control what you're doing and you're very clear about your choices, be sure you're open to the magic that happens in the moment. Be sure you're open to the moosehead on the table even if you had another plan in your mind.

Q: NYPD Blue. How did you get on that show?

A: I met Greg Hoblit, who was one of the first producing directors. That position, which I'm doing now on Homeland, I believe is essential to creative storytelling in television. Steven Bochco was an incredibly powerful writer and showrunner, and Greg was the balance and the visual storyteller to that incredible writing. They were a formidable team.

But it was through Greg that I started directing there, and it was also a great experience. He had created a very specific style on that show — very much long lens, whip pans, moving camera.

When I came in, it was the first season; the show was still finding itself. It was really groundbreaking TV. Steven was a game changer.

Q: Let's talk about Freaks and Geeks.

A: Oh. See? A smile. Yes.

Q: Why?

A: It was one of those unique experiences. Judd Apatow, Paul Feig — it's Paul's personal story about growing up. The stories were heartbreaking. It felt like he captured what it was like to grow up. Everyone goes through heartbreak, first love, trying to fit in — but it was done in such a wonderfully unadorned way, with such heart and compassion.

And it had a brilliant cast that normally would never be on network TV. It wasn't the perfect-looking cast, where everyone is beautiful and doesn't look like anyone you went to high school with. Things felt real — the embarrassing moments and the pain of growing up. I loved it.

Q: Gilmore Girls. You directed the pilot. And the scripts were almost 80 pages long?

A: Yes. Well, I don't think the original pilot was 80 pages. As everyone got better doing Amy's dialogue [Amy Sherman-Palladino, creator–executive producer], they did it quicker and the scripts got longer.

When we were casting, we were looking for a 16-year-old girl who was very smart and very well read — but wasn't aware of how pretty she was or how she was perceived in the world, especially by boys. And that's tricky. Because if someone is really pretty at that age, they tend to know it.

When we found Alexis Bledel, she had only done two school plays. She's a wonderful actress and was great as Rory.

There were a couple of references in the pilot script — one was to Jack Kerouac — and a lot of actresses came in to read and they would say, "Jack Ker-o-ick." Amy and I looked at each other and said, "We can't cast someone who doesn't know who Jack Kerouac is. Or hasn't looked up how to pronounce his name."

The other reference was Officer Krupke from West Side Story. That was also mispronounced. It was like, "This is not going to work." Those two characters [Rory and Lorelai, played by Lauren Graham] needed to be very smart, and you needed to believe they knew what they were talking about.

Q: The West Wing … the first few episodes you directed were during Aaron Sorkin's time on the show. What was it like directing his dialogue?

A: Aaron Sorkin is one of the brilliant writers in film and TV. He is like a modern Shakespeare to me. As an actor, if you don't have his dialogue down cold, you can't rise above it and act the role. And from Tommy Schlamme — Aaron's creative partner and West Wing's producing director — I learned a huge amount about how to be a good producing director.

He's a master. He creates a great working environment for directors to do their best work. He empowers you completely, and he wants you to come in and make your own movie. I loved working on West Wing from the moment I stepped on that set.

Q: After season four, Sorkin and Schlamme left and John Wells took over day-to-day operations. Did the show change at all?

A: Yes, it did. With Aaron, it felt like Italy. The trains don't always run on time, you might not always have a script on day one, but it's delicious and unexpected and you're going to have the best pasta ever. It was a little chaotic sometimes, but it was extraordinary.

When John — who is one of the great producers — took over, it was a bit more Switzerland. It was much more organized, but it wasn't quite as unexpected. In the fifth season, the show was trying to find what it was going to be without Aaron. Once the election started with Alan Alda and Jimmy Smits, the show reinvigorated itself — and was amazing. It was not the same, but it was really good.

Q: Mad Men.

A: I was blown away by the pilot. Alan Taylor directed it. Matt Weiner wrote it. What a compelling, layered lead character [Don Draper, played by Jon Hamm] — not a good guy a lot of the time, but you can't help but like him, be moved by him and want to get to know him. I have to say,

I think with Homeland, Carrie Mathison, played by Claire Danes, is one of the few female characters who is as compelling and complicated and layered as a man. Not always likeable. And that's exciting, too.

Q: The visual style was very different than other shows.

A: I had a Mad Men episode that was unique, "Guy Walks Into an Advertising Agency." I've had a few of them in my career, where I got handed a script, and I panicked. I read it and I thought, "This is either going to be fantastic or a total disaster. It's so out of the box." I love that as a director, it's always a new thing.

Even though I've been doing this for many years, I'm always challenged by every new project in ways I could never imagine. You can never get arrogant. One is always learning.

That was the episode where someone brings a John Deere tractor into a party at the ad agency and it ends up cutting off a guy's foot. I designed it and storyboarded it like an action sequence; it was all shot in one day. There was one try at everything — the tractor going into the wall, the glass breaking — it was very challenging.

But it was exhilarating, because nothing like that had been on that show. It was so different. And very funny. One of the ad guys says, "My God, the man lost his foot!" and John Slattery [as Roger Sterling] says, "Just when he got it in the door."

Q: Homeland — you directed your first episode in 2012….

A: That was the beginning of the second season. They had called me for the first season, but I was an executive producer–director on another series and was unavailable. They came back to me in the second season and, luck of the draw, I got an episode that was written by the late, great Henry Bromell, whose parents were both in the CIA.

The episode was called "Q&A," and 40 pages took place in an interrogation room. What was I going to do to make this interesting? But then I realized, "I'm in this room with Claire Danes and Damian Lewis. I'm in this room with amazing writing and these two brilliant actors."

The producing director at the time, Michael Cuesta, who had directed the pilot, said to me, "Don't be afraid to be simple." That was an incredibly generous and smart thing to say, because with 40 pages, you can't rely on some crazy camera work to try to make it more visually interesting. You have to truly delve deeply into the material, into the characters, into the performances.

And the scene was written beautifully, so trust that. And I always like really smart characters — and I want them to be as smart as they can be. My favorite kind of Homeland scene is when two characters have completely opposing views and they're both right.

Q: In season three, you directed the first episode and joined the show as an executive producer. How did you balance your roles as producer and director?

A: First and foremost, I'm a director and I love directing and I love being part of the whole series, being there for the whole "novel."

But specifically as a producer, I want to be the producer that every director wants to have, in the sense that I want to give the director everything they need to tell their story in the best way, and be sure they have all the information — about the crew, the actors, whatever they're moving into — so they can knock it out of the ballpark.

But once they're directing, I'm not going to stand there and stare over their shoulder. We hire amazing directors, and we want their insight and their unique creativity. I'm around a lot in prep and I'm always there for support, but then on the set, it's their set.

Q: How have opportunities for women in the industry changed since you started?

A: I do feel that in the last couple of years — because the disparity has become part of the public zeitgeist, and there's been so much dialogue about it — things have truly started to change. I felt this before — when the statistics went up a bit in the past, I felt like, "Oh, good, it's changing. Hopefully this won't be an issue anymore." But then it's always gone back.

But I do feel there's been a seismic shift. It's not easy for anyone to become a director, but it shouldn't be more difficult for our daughters than for our sons; it should be an equal playing field. I've been mentoring women directors for many years now, and I think anyone in a position to mentor should do it, grab the hand of the next generation and help open the door.

I have been wonderfully mentored by men and women. I think the recent change is something that's good for both genders, so there's more of a balance. It's not trying to take something away from men, it's trying to balance something that has been so slanted in one direction for way too long.

Q: What do you like about directing?

A: I love being a storyteller. I can't imagine doing anything else. I love the process of collaborating with a team of incredibly talented people. And I love being surprised by the ideas that your team comes up with, which make the story better. As long as the story stays first and foremost, all of those different voices are wonderfully additive.

You have to be able to play and work well with others — that's essential — and channel people's energy toward one goal. It is a thrilling process. When it works and you've got the right piece of material and everyone's focused on the same thing, it's truly an extraordinary thing that we get to do.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 11, 2018