As someone who has been working in Hollywood for a long time, I'm often asked "So have things gotten better for South Asian representation since you started in this business?" And there is only one answer: "Of course." Of course South Asian representation has greatly improved since the days when I was starting out, where, if you wanted to pay your rent by being a working Brown actor, your choices seemed to span the comically-accented cab driver to the menacingly-accented terrorist. Where we are today is in no small part because of a cohort of South Asian writers, directors and actors in the '90s and early 2000s who fought to tell important South Asian stories without big studio or network support - before the age of the coveted "global streaming audience" - and against all the odds. Folks like Nisha Ganatra who brought queer South Asians to the screen in Chutney Popcorn, or Gurinder Chadha who told the story of a young Indian girl who wanted to play soccer. Mira Nair who portrayed an interracial relationship between an Indian-American woman and an African-American man in Mississippi Masala which was released almost 30 years ago.

So I am definitely heartened by the wide range of South Asian voices born of those pioneers that we now have access to in television and film - messy teens, powerful superheroes, romantic leads and lotharios, paranormal investigators, etc. - and how much broader our choices are. But when I'm also asked, "Do you think we still have a long way to go?" The answer for me is still the same: "Of course."

As far as we have come, it is still often the case that most South Asian stories that get green-lit or embraced by the industry have to have as a central element the protagonist's relationship to white culture - being rejected by it, seeking to be accepted by it, coveting some element of it, being ashamed of their own culture and so on and so on. The net result is that "our" stories don't get to exist without whiteness still somehow remaining at the center of our experience. In my own life I know for sure that I internalized the white gaze as part of who I was and believed (perhaps unconsciously) that the only stories that were interesting about me were those that had to do with my identity to whiteness, and that internalization was a kind of 'psychic colonialism' that I'm pretty sure limited me as a story-teller and an artist in terms of what I was even able to explore in myself. This is what made a film like Minari radical. It told a story about an immigrant family in a way that felt entirely un-preoccupied with "being understood." This is the sort of liberation that I believe all of us non-White creators deserve and should claim.

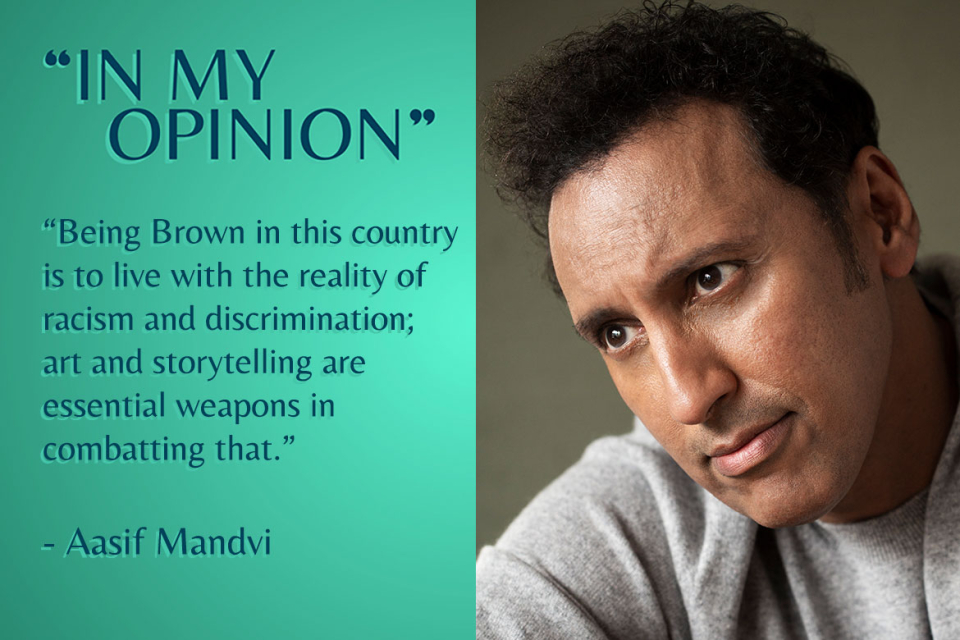

Don't get me wrong: I'm not overlooking the importance of stories that illuminate the experience of otherness or marginalization or exclusion that still rage on. It goes without saying that being Brown in this country is to live with the reality of racism and discrimination as a part of our lives, and art and storytelling are essential weapons in combatting that. But I think that if we're being really honest with ourselves, we also know that those are the stories that the majority culture often feels most comfortable telling because stories of ordinary people or the stories of simple human struggles are still seen as the domain of white people. Because for so long "normal" people on TV and in movies have been white people, everyone else was "other."

The exciting thing is that when I was coming up in the industry there was no space for this kind of conversation and so I'm glad there is now. As I look around at a generation that feels less shackled than I was, I am hopeful for the future and the kind of stories that we embrace in the coming decades.

Aasif Mandvi is currently starring on Evil for Paramount Plus, back for the second half of season two, next episode is on Sunday, 9/5, and This Way Up on Hulu.

Discover more "In My Opinion" articles.

The statements and viewpoints expressed in the article above are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily represent or reflect the opinions or viewpoints of the Television Academy, the Television Academy Foundation, or their members, officers, directors, employees, or sponsors.