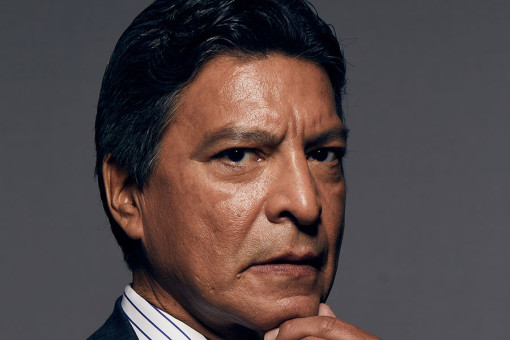

Wes Studi (Cherokee) is characteristically modest when asked about the Oscar, awarded him last October to honor his career achievements in films including Avatar, Dances with Wolves, Heat, Geronimo: An American Legend and The Last of the Mohicans.

He has the distinct honor of being the only Native American actor to have ever received an Academy Award. (Canadian-born Native Buffy Sainte-Marie won an Oscar for co-writing "Up Where We Belong," best original song from 1982's An Officer and a Gentleman.)

On the celebrated night at the Governors Awards held in Hollywood last year, the glittery crowd eagerly awaited the history-making moment, which Studi first met with humor before turning serious.

"I'm amazing. The way these people will tell it, I'm absolutely amazing," Studi said with a smile as he began his acceptance speech, after being feted by Christian Bale, Q'orianka Kilcher and US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo. "I'd simply like to say, it's about time. Ladies and gentlemen, it's about time."

"Amazing" can also describe Studi's career, which began in community and dinner theater and educational television before he broke out in 1990's Dances with Wolves, the Oscar winner for best picture and recipient of six other Academy Awards.

He had moved to Los Angeles from Tulsa, OK in the 1980s to take a shot at being an actor. It was a time when Hollywood was taking an interest in more authenticity in casting after a shameful track record of casting white actors in Indigenous roles.

With the help of a now-defunct organization called the American Indian Registry which promoted Native actors, Studi got an agent and booked a role in Kevin Costner's landmark film. Another career-making part soon followed in the Michael Mann-directed Mohicans.

Yet looking back on his role in it as Magua, a fictional Huron Indian chief based on the character from the 1826 James Fenimore Cooper novel, he says Native audiences especially would have appreciated an explanation of his character's motivations for revenge.

While many of his roles have been in historical pieces, Studi believes accurate representation of Native peoples is best displayed in contemporary stories.

"Shows like Yellowstone afford a better solution exposing people to Native culture," he says during a phone call from his Santa Fe home. "I find it sometimes disappointing that some roles offer little more than two-dimensional characters. We don't really get to know who they are or what drives them.

"Contemporary shows about Native Americans are generally not accepted as marketable and bankable. It hasn't worked out so far. The Red Road [on Sundance TV in 2014-15] lasted only two seasons."

Yet Studi sees that young Native filmmakers are becoming recognized in the industry and beginning to make their mark. That in turn provides more opportunities for actors, opportunities that are still more abundant than for below-the-line positions.

"The social atmosphere has created the need or impetus for diversity in casting, certainly giving a boost that includes Native actors," he says. "The opportunity is going to be there, but it's up to the actor to be ready when it comes along. It's a matter of looking outside the box in terms of casting Natives in parts not necessarily written for them.

"Many Natives who have names like John Smith can be recognizably Indian. Casting and production people should begin to think in those terms and make film more representative of the world we live in."

Studi himself has had those kinds of opportunities among his nearly 100 film and television credits.

"I've been fortunate to have roles in films where they looked outside the box," Studi says. "I played a policeman in Heat, a villain in Street Fighter, a wannabe superhero in Mystery Men. Those opportunities came from people willing to think outside the box."

At the same time, non-Natives - and those who claim to be - are still being cast in roles defined as Native, especially for parts in period pieces or Westerns that Studi and other members of the community call "feathers and leathers."

"It's a matter of conscience of those who would claim to be Native. What they're doing is denying another an opportunity. It's a sensitive situation in that we want to play parts not necessarily Native, then we gripe about non-Natives playing Natives. It's a double-edged sword," he says.

Reflecting on the era of Native American activism which began in the late 1960s, Studi says it had an impact on storytelling in film, but that the pendulum swings back and forth.

"The activism created an interest in 'Who are these Native people running around claiming rights?' The business saw that and put out films with a degree of Native American content. Show business is definitely a business, let's recognize that. Clever writers are those who can include what's interesting to the public at the time. That's how I think Hollywood responded to the American Indian Movement (AIM)," he says.

As for today's racial reckoning, Studi hopes it brings a realization that his community and the diverse cultures within it are seen as equal citizens in America.

With three films in production, including one he's executive producing, and nine listed in development, Studi is optimistic not only about his own projects but about an improving landscape for other Native and Indigenous people.

"There are billions of stories in the world and we are the subject matter. We are developing real filmmakers who are going to bring more to the table than in my era of actors, acting in stories written by non-Natives and being able to be part of it. The interest remains," he says. "Our writers tell stories that show more of our real selves. That's what Native audiences have been looking for, for a long time, characters that are fully developed."

Read more on Native American inclusion in the television industry.