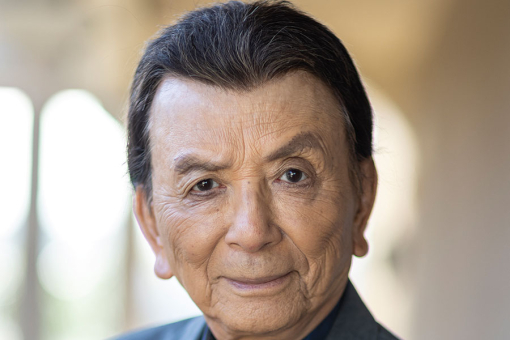

Television pioneer Rita Lakin knows a thing or two about being the only woman in the room.

In fact, she made that phrase the title of her 2015 memoir, which recounts her successful career in television.

A lifelong writer, Lakin started in the industry as a newly widowed secretary in the 1960s with dreams of selling a script. Once she achieved that goal she kept going, with roles as staff writer (on Peyton Place) and story editor (on The Mod Squad), eventually creating shows (The Rookies, Flamingo Road) and serving as executive producer (Executive Suite).

Lakin's industry education began when she bought a book on how to write scripts and continued as she observed the production process in every job she took. She persisted in the business despite her constant outsider status.

"I didn't really think I belonged there because it was a man's world," she says. Even when she took a position that no other writer wanted — and ended up being mistreated and overworked — she kept moving forward and counted it as an educational experience: "I didn't know it, but I was learning everywhere I went."

Lakin was interviewed in May 2017 by Adrienne Faillace, producer for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire discussion can be screened at TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

Q: How did you get into writing?

A: I was always writing something or other. I started writing short stories. But I didn't know that you did anything with them, so that was about it until I got married.

I had a best friend — she and I used to write short stories all the time and we actually got to sell them. Somebody had told me that if you want to sell action-adventure stories, they don't buy from women, so don't give them your real name. My first story went to a magazine called Manhunt, and I was R.W. Lakin. They didn't know that I was a female.

Q: So how did you start writing for television?

A: We moved to Los Angeles because my husband had a job there as a physicist. He died very young, and I was left with three small children. I had to go to work, but all my friends were housewives, and I didn't know what to do.

I went to all the movie studios and got a job at Universal as a secretary. I wasn't making that much money, but I was reading scripts and thought, "Well, I wrote short stories… maybe I could learn to write a script."

I bought this book, Teleplay, and it gave me instructions. I learned that I should have a script ready, because one of these days the door is going to open.

I started watching TV, and the show that I thought was really interesting was Ben Casey, so I wrote a big script for it. At Universal, I was working for these two wonderful young men, Ned Tanen and Dale Sheets. They encouraged me.

Agents would come in and Dale would say to them, "Here's a new writer for you." Usually people ignored me. But in came Mel Bloom, and he really wanted my boss to give him business. So when Dale said, "She's a really good writer," he said, "I'll take your script home and read it." I thought I'd never hear from him again. But he came back and said, "I got you a job, maybe. We're going to go to Richard Chamberlain's show."

Though I had written for Ben Casey, the characters were entirely different for Dr. Kildare. I practiced in front of a mirror all the story ideas I was going to try to sell.

When we went into a meeting, there was David Victor, a cheerful guy, along with this nice-looking young man. I was very nervous and kept trying to pitch ideas, but they kept saying, "No, we've done that." I was introduced to the young man and it was Sydney Pollack, who was going to direct my show. This was his first job.

Q: Oh, wow.

A: He was very nice. They both were very helpful to me. I'm sure my first draft must have been horrible. My agent had said to David Victor, "Be nice to her. She's a widow trying to take care of her children."

So what did he want me to write about? A woman who becomes widowed. I thought, "Oh boy, they knew about me and that's what they wanted." But when I met the little boy who was going to play the son, it was Ron Howard. I think he was already a star — he was Opie [on The Andy Griffith Show]. So it was an amazing experience.

Q: From there you freelanced a number of episodes, and in 1965 you got your first staff job as a writer on ABC's Peyton Place ….

A: I finally felt that I really was a writer and I would have a career doing this. And I was very excited because I was going to be working with other writers. There were seven of us, [including] three women. It was the first time I'd seen women writers anywhere. We got along amazingly. I think they were as glad to see me as I was to see them. It was the best job I ever had.

Q: Did you interact with the cast members?

A: I still had the newcomer-woman attitude. I hardly visited sets, but by this time I had started to watch the dailies. I at least knew enough to do that.

Q: What did you learn from that?

A: I learned a lot. What worked and what didn't. And how important editing was. I didn't know it, but I was learning everywhere I went.

Q: Mia Farrow famously cut her hair quite short during the run of the show. Were you there at that time?

A: Yes I was. We were all outside doing other things and our secretary called hysterically and said, "Come back, come back! Emergency!" We had to run back and come up with a new story, so we decided [her character, Allison MacKenzie] had had a car accident and brain surgery, and they'd had to cut off all her hair.

To this day I'll never understand why they didn't just put her in a wig. To go through so much trouble with that hair… Then this very short haircut became the style all over the country. That's when I saw what stars could accomplish, how important they were.

Q: In 1967 you were hired as head writer on the NBC daytime soap opera, The Doctors ….

A: That was a funny experience.

Q: How so?

A: Well, by then I really had a career. I was writing a lot of movies for television. But my folks lived in New York, and I was never finding time to visit. This show was filmed in New York, and the creator, Orin Tovrov, came to L.A. and called every writer in the Writers Guild to a party at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Of course, everyone came — free drinks, free food — but not one of them intended to go to New York and write a soap opera.

I said to myself, "It's only six weeks. My kids can visit their grandparents — it's going to be wonderful." So I took a job that nobody else would take.

It was a funny experience because I got to see my children only once. I was supposed to be the head writer and given other writers. But since Tovrov had gotten a nighttime [soap] writer, he decided he didn't want anyone else. I was writing all the shows, five a week. I never got out of that little apartment that I sublet. Carnegie Deli brought me breakfast, lunch and dinner every day.

Q: How did you feel about writing for daytime, coming from primetime?

A: I had the same attitude everybody had, that daytime was way below nighttime in quality. In a sense it was true, because you had five shows a week. So what you might have done in five minutes on a nighttime show, you stretched out to a week for daytime. It was very easy to write.

Q: I read that one of the directors [Rick Edelstein] started to write some scripts….

A: He did. He knew the truth about why they wanted a nighttime writer: the show was about to be canceled. And I did save the show. The ratings were just about in Cancelville. It was the number-one show when I walked off.

Q: In 1969 you became a story editor on the ABC series The Mod Squad ….

A: Yes. I didn't really get into the business until Mod Squad. I wasn't a writer for Mod Squad per se, I was a story editor. I was now on the business end, and it also was my introduction to Aaron Spelling, who became very much a part of my writing life. He welcomed me.

That's when I decided I really wanted to learn the business. I was with the producers all the time, and I was on the set a lot. I was rewriting scripts, and I wrote a couple of my own.

Q: One was "In This Corner — Sol Alpert." What was that about?

A: I was writing about downtrodden people living in terrible circumstances [who take revenge on the rent collector]. I didn't know I was doing something new for television, that this was not just a Mod Squad story where they went out and got the bad guys. This was a story about real issues. And it got me a nomination for a Writers Guild Award.

Q: What were your initial meetings like with Aaron Spelling?

A: He was quite a character, a skinny little guy with a sweet Southern accent. He was ever so charming. He was obviously very smart and he got to be very successful. He had one idea that he carried through all [his shows]: gorgeous women and gorgeous men looking gorgeous and doing exciting things.

Q: What were you learning about production on the show?

A: I was finally going to the meetings. At the first one I went to, they discussed how to do my episode of Mod Squad.

Q: That's where they mark up the script and outline what each department needs to do?

A: Yes, which was a very funny experience to me. Because everybody was there — transportation, makeup, hair — plus Aaron and the director. They were going page by page: "We need a truck here, we need a dirty room here…." Every time it came to the dialogue, they would go, "Words, words, words." That was a revelation to me, that production was not the least bit interested in the words.

Q: Did you start to have ideas about being a producer at that point?

A: No, that came later, with the same revolution that was starting to happen in the business, and certainly Steven Bochco was at the forefront — that if the networks wanted the script done right, they should have the writer involved in the production. That was the beginning of the idea of a showrunner.

But funnily enough, I became a showrunner even before Steven Bochco. I got an idea for a series that they wanted me to write, which was Flamingo Road. My son Howard had gotten into the business by that time, so he wrote the pilot script and they asked me to produce the show. That was a good experience. I really enjoyed Flamingo Road.

Q: You were the first woman showrunner?

A: Yes, I was, but nobody knew that. We had no words for that. They called me executive producer [on the CBS series Executive Suite]. The second time [on NBC's Flamingo Road] I was the supervising producer.

When Bochco got to do it and changed Hollywood's whole attitude about TV, that's when the showrunner credit started. But that's what I was doing. They hired me because they wanted me to run the show and make it succeed. Before that, the attitude toward writers was: keep them as far away from the set as you possibly can.

Q: In 1972 you created The Rookies. Tell us how that came about.

A: That's kind of an amazing story. I hardly ever tell it to anybody, because who'd believe it?

Aaron Spelling was no longer at a major studio. He was looking for projects, so I pitched him an idea for a movie. He was very agitated, which was strange, because he's usually very laid-back. I asked, "What's wrong?"

He said, "ABC wants me to come up with an idea for a new series and the deadline is in 15 minutes. I've been trying to find an idea for months, and I haven't come up with anything they'll accept." I said, "I'm sorry to hear that." I started to pitch my idea and said, "Aaron, you're not listening." He said, "I can't…. I'm worried."

Unbelievably, I said, "Well, why don't you just give them Mod Squad all over again?" He said, "What are you talking about?"

I had to think on my feet — that was the biggest lesson I got out of working on that soap opera. I had to come up with a great idea in 30 seconds. I said, "Why don't you do something called The Rookies and instead of boy cops in the field, have boys becoming cops?"

He said, "You know, that might work," and dashed over to the phone and called ABC and said, "I think I have the show." He hung up and said, "It's sold."

I went into shock.

He said, "I am now going to make you rich." I said, "Thank you," and I left.

Now, when you come up with a show idea, you get "created by" credit, which is the best credit you can get. So I had "created by," and I handed in my script and I didn't hear anything. I asked, "Aaron, what's going on?" He said, "Come to the ABC meeting with me. They're not happy." I went to the meeting and they kept saying, "Where are the shoot-em-ups?"

When we left, Aaron was not happy. I didn't hear from him, and he was avoiding my calls. Aaron did not like to do anything that was unpleasant. I waited, and then I read in the trades that there was a new writer writing my show, Bill Blinn.

Bill was a very good writer, very successful. He thought he was the original writer. He thought he was getting the "created by" credit, and he was not very happy to find out that he had to take "developed by," which was less money, less cachet.

But that was Aaron doing an Aaron. He didn't tell Bill the truth. He just said, "I want to do a show, and this is what I want it to be about." So I didn't go to the set. I didn't write any scripts. I didn't have anything more to do with it. And I never got rich.

Q: Let's talk about an episode of Medical Center that you wrote in 1975.

A: Every one of their shows centered on an important issue, and I did two of them. I really loved the second one: a story about women who wanted to become surgeons. At that time men did not want women surgeons.

But the one I did with Robert Reed was world-changing. The producers of Medical Center wanted me to do a show about a transgender character. I had never before heard the word; I didn't know what it meant. Then I was told what it meant and that Robert Reed was playing the lead, which was very interesting because insiders knew that Robert was gay. For the first time, really, I did a lot of research.

I found out all the steps that Robert's character would be going through. The producers were so thrilled, they made it into two episodes, which was astonishing to me.

Q: This was "The Fourth Sex."

A: "The Fourth Sex." It was an amazing success, and Robert got nominated for an Emmy for it.

Q: Let's move on to Nightingales.

A: Aaron Spelling called me for yet another project. He called me a lot, and often I said no, because it was just going to be these girly-girly things. At this time I was at the top of my career. I really didn't want to do this show. He wanted to do a show about nurses, and instantly I knew Aaron's mindset: naked nurses getting out of the shower, getting in bed with somebody.

But I thought, If Aaron wants me, I'm going to take as much money as I can get and put my friends and my son on the show. So Howard and my friend Frank Furino and I created that show. We created the show we wanted to do, which was damned interesting.

And then it all fell apart because of Aaron. There was a book that was written about the show, and I had no idea what was going on behind our backs until I read this book.

The irony is, Aaron was really ahead of his time. The show he wanted could have been on Showtime. But it was too soon. I got fired, Frank got fired and I guess Howard must have gotten fired, too. And that was the end of my career.

Q: What happened?

A: There was a writers' strike [from March to August 1988]. And the strike did something very interesting. The networks were trying to save money, so they got rid of every writer who made too much money, and I was on that list. I couldn't get a job after that. I was being told by secretaries that when they'd listen in on meetings, my name would be mentioned and they would say I was too old.

So that was the end of it. I was out of television.

Q: How would you like to be remembered?

A: That I tried to do really good things in television. And tried to help other people. For having done some things that mattered, even though I didn't even know it at the time.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 2, 2018